|

Building a Wooden Sailboat: The Design,

Build, and Launch of the Whimsey

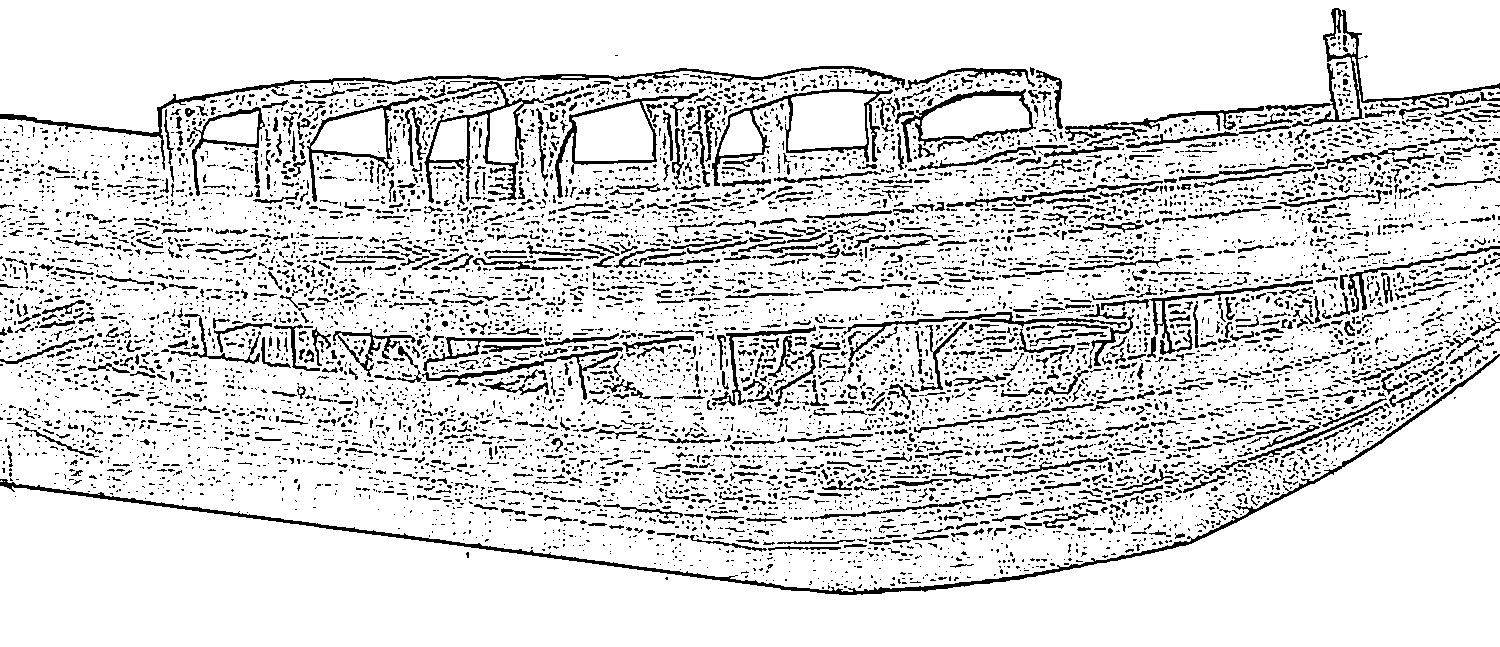

Planking

and Bowsprit

It

was only about September or October that I began to think

of making a raft. By that time my arm had healed, and both

my hands were at my service again. At first, I found my helplessness

appalling. I had never done any carpentry or such-like work

in my life, and I spent day after day in experimental chopping

and binding among the trees. I had no ropes, and could hit

on nothing wherewith to make ropes; none of the abundant creepers

seemed limber or strong enough, and with all my litter of

scientific education I could not devise any way of making

them so. I spent more than a fortnight grubbing among the

black ruins of the enclosure and on the beach where the boats

had been burnt, looking for nails and other stray pieces of

metal that might prove of service. H. G. Wells - The

Island of Doctor Moreau

When I began

planking I started at the line of the upper deck. First I had

to wait until the planks were finished by the mill. I'd requested

them to be planed to a thickness of three quarters of an inch

(1.9 cm), only to find that when I went to pick them up they were

only planed on one side. How the instructions got lost I had no

idea, and I couldn't imagine how the guy who planed them thought

I'd be moulding rough-cut planks to the ribs, but I needed them

re-planed. I told them about the mistake, and they said they'd

redo them, which meant that I lost another eighth of an inch (.31

cm). Once I'd guessed at the flexibility of the wood by what I'd

been using, I figured that the mistake was in my favour. The thinner

planks were easier to steam and bend.

I rabbeted

the stem by running the circular saw over it along the line I'd

drawn, and then finished the fine work with a chisel. I was impatient

to get to the planking, so I could easily have done a better job

on the rabbet. It was perhaps 3/8 of an inch (.95 cm) deep and

more or less on the desired angle, but in retrospect it would

have been better to have spent more time cutting the rabbet so

that it would more easily match the planks.

Rather than

lose timber by scarfing the joins, I butt-blocked two planks together

with glue and deck screws. That gave me over twenty feet (6.09

metres) of planking that would easily reach from stem to stern.

I steamed the first plank by boiling water in an electric kettle

and then pouring that over t-shirts I wrapped around the plank.

When the plank was thoroughly steamed-at least as much as I needed

and could do without a steam box-I clamped it to the central ribs,

and then worked from amidships aft and forward. When I was fitting

the plank to the stem I needed multiple tries to get it into place,

each time clamping it nearly into place and then trimming it with

the electric planer. When I finally had it clamped to the outside

of the transom and connected on an angle to where it would meet

the stem properly, I used the industrial polyurethane glue and

clamped and then deck-screwed it into place. It was a procedure

which took a few hours, and when I finally had it seated, I scraped

away the glue and began to work on the next plank.

I'm sure that

someone working from professional plans would have done a much

better job. They would have known the exact angles and dimensions

which would mate the planks to the ribs, but I had no such advantages.

In all my research for boat plans, I saw none that matched what

I wanted. I had no choice but draw up my own plans, and for every

hour I gained by avoiding the calculations which would lead to

more detailed plans, I spent my time trimming and measuring and

cutting and sanding.

Once the top

plank was in place, I decided to work on the garboard, the one

nestled in beside the keel. Although I wouldn't advise it now

that I know better, I decided to cut a two-inch (5 cm) plank and

then install it by gluing it to the keel, screwing it in place

through the body of the thin plank and by screwing and gluing

to the ribs. This meant the ribs were more securely held in place,

and the garboard operated as part of the structure holding the

ribs to the keel. Normally a wooden boat would have the plank

along the keel cut on a long curve to a point, and it would be

connected to the next plank in a way that the middle of each would

make up the difference between the middle planks and the bottom

ones.

Unfortunately,

the way I did it-running a narrow plank along the keel and up

towards both the transom and the stem-also left me with awkward

ends of the plank. The forward end needed to be cut on a long

angle to fit the next plank as it walked up the stem, and the

ribs needed to be cut on an angle to hold the angled plank. That

meant using the planer to insert a slope that would have been

better to have cut into the ribs originally. I trimmed it into

place, although I wasn't happy with its fit, and then went back

to the upper plank to fit the next one down.

I spent many

days on the planking, even though Joshua Slocum had glossed over

the matter in one line: "The planks for the new vessel, which

I soon came to put on, were of Georgia pine an inch and a half

thick. The operation of putting them on was tedious, but, when

on, the calking was easy."

The next glue-up

was more demanding, but after I got the hang of the amounts I

needed to trim away to fit the plank to the stem, and let it overhang

the transom so I could trim it later, it became much easier. The

bend at the prow was abrupt, but the steaming proved to be sufficient

to pull the plank into place since I was using both large c-clamps

and deck screws to hold it. Once the glue fastened the second

plank to the first one, with clamps squeezing them together, I

was ready to let the glue set.

In many ways

those were the easiest planks to fasten, for they had little curve

or twist, and the transom was nearly perpendicular to the floor

at the upper end. I continued adding planks to the bottom of the

hull by cutting them on an angle to admit the next plank, and

then edge-gluing them in place. By May 13th I had several of the

lower planks on both sides and the same two at the gunwale. I

would hold one plank alongside another by using a block of wood

under the clamp, and for others I fastened them by glue to the

ribs and the plank next to it, as well as long deck screws. It

was far more robust that it needed to be.

One disturbing

problem I was beginning to notice was the keel was nowhere near

as deep as I'd planned on. Because some of the upper keel was

embedded in the ribs, and almost an inch (2.54 cm) of it was covered

by the planking, the original nine inch (22.8 cm) keel was down

to six (15.24 cm) or seven inches (17.78 cm). Although that meant

I would need to deepen the keel if it was going to act as a lateral

force against the water while I was sailing, I figured I could

save that problem for another time.

The next issue

was the cabin superstructure. I started with the companionway

by timbering either side of what would be the main hatch, and

then closing in the bulkhead with quarter inch (.635 cm) plywood.

It was mainly needed to close off the space, and only part of

it was meant to be structural, but I still glued it to the timbers

as well as used drywall screws to hold it in place.

The next few

weeks as the month of May drew to a close were busy ones. I spent

a generous amount of each day installing planks, reshaping and

fitting them to bond with the plank beside them as well as the

ribs and stem, all the while butt-blocking their joins. After

three hours or so of fitting a rib and making it ready to glue,

I would begin the next one on the other side. Setting one plank

per side meant I could brace the plank with boards between it

and the next, and then partially clamp it by wedging cut off pieces

from the rest of the timber into the gaps.

That still

left me with a few hours free every day, so I began to work on

the forward deck. It was meant to be a solid piece of 1/4 inch

(.63 cm) plywood, and, like the cabin roof, to flex both sideways

and forward and aft for added strength. I also needed to allow

the Sampson post to protrude through the centre and the deck needed

to be notched for the stem. It was finicky making sure the centre

cutting worked, but once I had it in place, I left the sides rough-cut

because I knew I could trim them later with the planer.

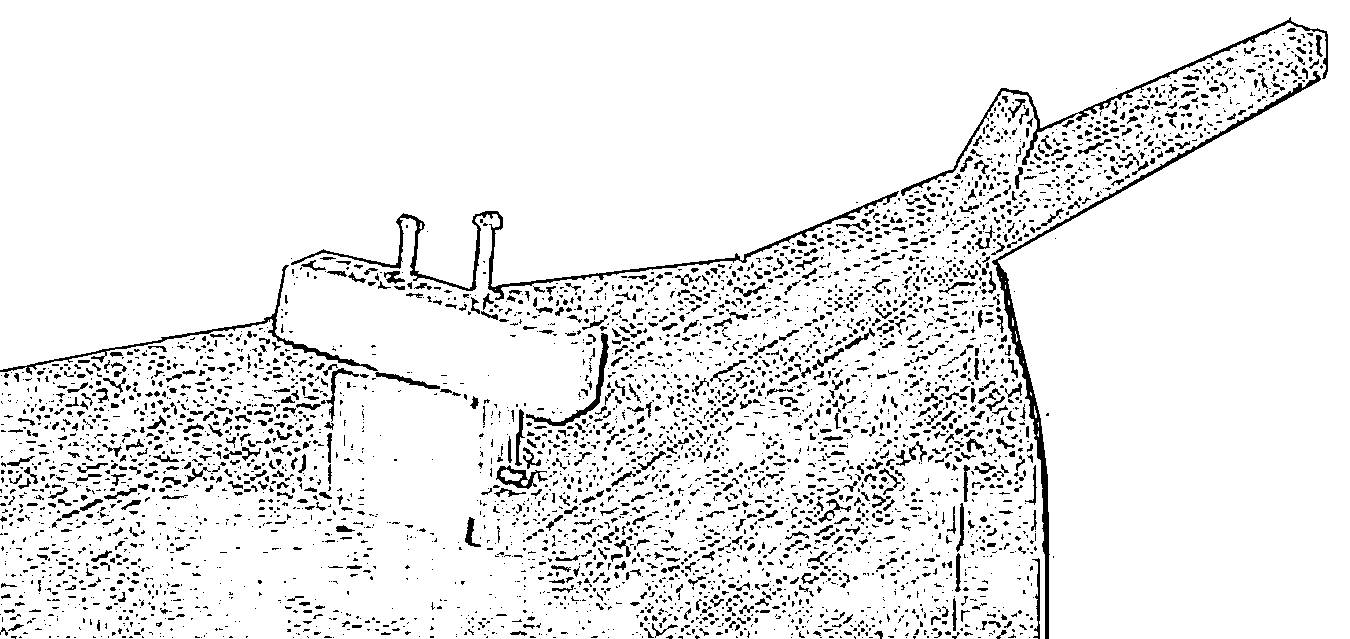

The last part

of the prow which I settled into place was the bowsprit. It had

been made earlier from a thick 3 x 5 x five foot (7.62 cm x 12.7

cm x 1.54 metres) piece of clear Douglas fir. I had cut it into

a long triangular shape, notched the end so that it would fit

around the Sampson post, and settled the centre of it over the

stem. Pins held it in place over both timbers, but it was not

otherwise fastened. I wanted it to be removable in case I needed

to trailer the boat. The timber was much thicker forward than

it was aft, for its strength went into two planes depending on

what was needed. Forward, the bowsprit extended two feet (60.9

cm) over the stem, and back along the decking for another twenty

inches (50.8 cm). It needed to be sturdy to hold the standing

rigging-although I intended to support it with a water stay so

that the forestay wouldn't force it up or the jib break it when

I was under sail.

Once the bowsprit

was fitted to the hull, I carried on with the planking. The hull

was gradually being closed up, and the only issues I had besides

the hard work was the litany of negativity coming from my sister's

neighbours when she brought them to see the monkey show. They

would never enter the garage using the door, but would instead

stand while my sister threw open the main door. Even if I said

hello, they never addressed me, so I just carried on with my work

and addressed their complaints as they made them.

|