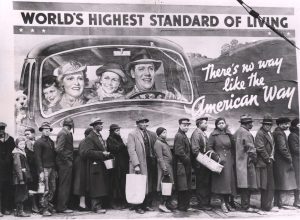

Each generation visits its sins on the next, just as children will grow up to have their teeth set on edge by grapes if their parents have learned to be sour. Since the great depression, two more generations have struggled with their questionable inheritance, and performed their own lives in reaction to the privation of their youth, or the excess in which they nearly drowned as children.

The depression era people learned valuable lessons from their time. Perhaps despite their own desires for the trinkets and trash of their era, their poverty meant that they quickly learned that consumer items that did not last  were not worth buying. They learned to value the physical item in the world for the work that was required to produce it, to treasure its ephemeral presence, and because it would often be impossible to replace, to mourn the tragedy of its loss. As the post-war period came to North America and of all the money we had given to the war machine some was returned, we experienced a brief moment of wealth and comfort. Disposable consumer items burgeoned to fill the niche of the new consumer, and the children of the depression-era parents ran to the Walmart in order to recoup the lost youth that they felt that frugality and privation had denied them.

were not worth buying. They learned to value the physical item in the world for the work that was required to produce it, to treasure its ephemeral presence, and because it would often be impossible to replace, to mourn the tragedy of its loss. As the post-war period came to North America and of all the money we had given to the war machine some was returned, we experienced a brief moment of wealth and comfort. Disposable consumer items burgeoned to fill the niche of the new consumer, and the children of the depression-era parents ran to the Walmart in order to recoup the lost youth that they felt that frugality and privation had denied them.

The antithesis of their parents, the Walmart generation became actively, frivolously wasteful, as if they were possessed by an unconscious desire to throw away the wealth of the world as quickly as possible. Christmas  became about the wrapping, as the contents of the presents under the disposable tree were discarded as quickly as the packaging. They bought furniture for fashion, required closets for the many kilos of clothes they accumulated, traded cars as new models appeared, and in every way embraced the new-and-improved disposable culture. A fast food generation of hamsters and goldfish, they viewed everything around them with an eye to when it could be thrown away.

became about the wrapping, as the contents of the presents under the disposable tree were discarded as quickly as the packaging. They bought furniture for fashion, required closets for the many kilos of clothes they accumulated, traded cars as new models appeared, and in every way embraced the new-and-improved disposable culture. A fast food generation of hamsters and goldfish, they viewed everything around them with an eye to when it could be thrown away.

Living in a rapidly growing trash heap, they taught their children to think of the world as disposable, wildlife as pets, pets as toys, toys as momentary distractions, and distractions as their sole reason for breathing and excreting. Their children learned to reach for the paper towel before the rag, the coffee pod instead of the grinder, and plastic where there had been wood or metal.

In time however, having learned to discard the entire world from their parents, the children of the Walmart generation wanted to throw away their forebear’s grotesque consumerism. They were disgusted by the gauche way in which their parents assembled fine art with plastic trash, and fancied themselves as different from their philistine ancestors. Although an apple might come from a tree, it can only roll so far, however. Their horror at their parent’s excess only took the new generation so far along the path to environmental enlightenment.  They rejected the rampant consumerism with its disposable cups and plastic clothes. They bought cotton and wool, fancying them to be more sustainable. Unfortunately, they bought even more clothes than their parents—who even in their rejection of the extreme husbandry of their own parents were not as wasteful as this new generation. They wore their organic cottons as if they were environmental statements, wore them a few times, and then took them to the thrift store, little thinking about the waste they were producing. Instead of the disposable plastic water bottle,

They rejected the rampant consumerism with its disposable cups and plastic clothes. They bought cotton and wool, fancying them to be more sustainable. Unfortunately, they bought even more clothes than their parents—who even in their rejection of the extreme husbandry of their own parents were not as wasteful as this new generation. They wore their organic cottons as if they were environmental statements, wore them a few times, and then took them to the thrift store, little thinking about the waste they were producing. Instead of the disposable plastic water bottle,  they bought a reusable bottle at forty times the plastic and ten times the energy to produce. And because these declarations of caring grew faded, or scuffed, or unfashionable, or popular, they donated those as well, and bought others, using in the process more plastic and energy for manufacturing than ever.

they bought a reusable bottle at forty times the plastic and ten times the energy to produce. And because these declarations of caring grew faded, or scuffed, or unfashionable, or popular, they donated those as well, and bought others, using in the process more plastic and energy for manufacturing than ever.

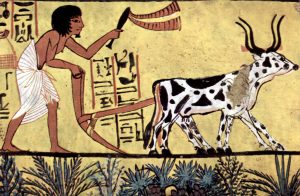

This new generation, much more conscious of environmental concerns than their parents, were nonetheless still their children. A strange blend of consumerism with care-about-the-earth branding, they bought just as much, but no longer supported the Walmart. The new brand, instead of the label cheap-and-mass-produced like their parents had often worshipped, was expensive-and-environmental, although the latter didn’t play out in execution. With the dumps beginning to grow with their environmental contributions, some of their children, and some of the new generation as well, began to turn their back on the conspicuous consumption that had marked sixty years of landfills and oceanic plastic. Floundering about for guides to  their behaviours, they embraced permaculture, a new trend strikingly similar to the farming practices of thousands of years of our ancestors. In the place of waste, they began to reuse, upcycle, and swap, and in that way rebuild a marketless and moneyless economy that was produced organically by the desperation of the depression.

their behaviours, they embraced permaculture, a new trend strikingly similar to the farming practices of thousands of years of our ancestors. In the place of waste, they began to reuse, upcycle, and swap, and in that way rebuild a marketless and moneyless economy that was produced organically by the desperation of the depression.

Many of those who lived during the depression are gone, and if they still are alive they are likely in nursing homes where their lives are littered with disposable diapers,  single-use medical tubing and paper napkins. From that trash heap, however, they no doubt recognize this most recent generation of seekers, who have returned to the fold after straying from the way. Squinting through the newly replaced thermopane windows of their poorly built nursing home, they no doubt applaud this latest attempt to live responsibly, to avoid treating the entire world as a trash heap, and understand from their dotage, a wish to touch the world without its plastic wrapping.

single-use medical tubing and paper napkins. From that trash heap, however, they no doubt recognize this most recent generation of seekers, who have returned to the fold after straying from the way. Squinting through the newly replaced thermopane windows of their poorly built nursing home, they no doubt applaud this latest attempt to live responsibly, to avoid treating the entire world as a trash heap, and understand from their dotage, a wish to touch the world without its plastic wrapping.