When Biss and I decided to take his son on a canoe trip, I suggested a lake I’d gone to before. We would be canoeing in the dark, which we often did, and that  lake afforded opportunities that other locations didn’t. For instance, Aaron had a terrible sense of direction, paid more attention to impressions than specific details, and would therefore have no idea that we were retracing the same path or going in circles. And that was exactly what I planned to do.

lake afforded opportunities that other locations didn’t. For instance, Aaron had a terrible sense of direction, paid more attention to impressions than specific details, and would therefore have no idea that we were retracing the same path or going in circles. And that was exactly what I planned to do.

I wanted Aaron to have a grand adventure, although that wasn’t as easy canoeing near their house. Therefore, I decided we would make an adventure out of a rather mundane canoe trip, much like parents  make hiding places from blankets and chairs in the living room. A child’s imagination is a caregiver’s best ally, and with only a little prompting I knew Aaron would have the trip of a lifetime.

make hiding places from blankets and chairs in the living room. A child’s imagination is a caregiver’s best ally, and with only a little prompting I knew Aaron would have the trip of a lifetime.

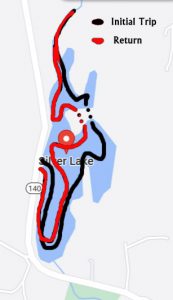

We put the canoe in the water near where we parked the car, across from a small beach. Then we canoed along the shore and then across the lake toward the now-vacant beach. Aaron had no idea where we were going, and in the dark, he had little sense that we weren’t going in a straight line. Once we arrived at the beach, which I skirted closely for effect, we canoed to a kind of peninsula which stuck out from shore in  the narrow part of the irregularly-shaped lake. We pulled the canoe onto the shore and told Aaron we needed to portage to get to another lake. We carried the canoe some thirty metres until we arrived on the other side of the peninsula, and then set out again on the farther part of the same lake.

the narrow part of the irregularly-shaped lake. We pulled the canoe onto the shore and told Aaron we needed to portage to get to another lake. We carried the canoe some thirty metres until we arrived on the other side of the peninsula, and then set out again on the farther part of the same lake.

Aaron’s attention was such that he was sure we were in another lake, and that it had been difficult to get to. We canoed to the far end of that lake, and then began to follow the small stream which fed it. The banks became closer and the trees overhung the water, all of it contributing in Aaron’s mind to a voyage up the Amazon. Once the trees began to crowd the canoe, we pushed them to one side and kept going, until finally too many logs choked the stream and we turned around. Aaron was more than done by the creek by that time, for the closeness  of the bank and the thrashing of small animals in the woods at night, contributed to a sense that we had really gone off the map.

of the bank and the thrashing of small animals in the woods at night, contributed to a sense that we had really gone off the map.

The way back was longer, naturally. We followed the other side of the lake, keeping as close to the bank as possible and telling Aaron about possible logs or rocks in the water that he needed to watch for. Then we went back across the lake to our earlier portage pull-out spot, and hauled the canoe to the other side of the peninsula. I told him it was time for us to rest, and I pulled out some matches and began to gather stones. I bade him to pick up sticks and before long we had a fire flickering under the pine trees on the hill. We sat on the ground talking about the remoteness of the woods and pondering what staying the night would look like if we needed to. Finally, I doused the fire with mud and we clambered back into the canoe to go back to the car.

remoteness of the woods and pondering what staying the night would look like if we needed to. Finally, I doused the fire with mud and we clambered back into the canoe to go back to the car.

We crossed the lake again, and then followed that bank until we were opposite the beach. Then I crossed to the beach and reminded Aaron that we were retracing our steps. We followed the edge of the lake from the beach to the car and then we were ready to go home.

Although the entire adventure didn’t take any more than two hours, for the lake was very small, Aaron still mentions it. Our voyage of dozens of kilometres in the dark—although it was more like two or three kilometres in total—is still burned into his mind, although that has much more to do with his imagination than anything that we did.

When I was young I remember hiking to the back field with my brother Blake, and how, at six  years old, the area we called the black woods were frightening enough that I feared stepping off the trail. On one occasion we walked around the perimeter of the field and I saw, glowing in the late spring, a weed- and grass-strewn path angling out of sight but promising delight if we were to follow it. I wanted to take the path, but Blake said we didn’t have time. Nonetheless, that enduring image has informed many of my ways of thinking about both imagination and a child’s perception.

years old, the area we called the black woods were frightening enough that I feared stepping off the trail. On one occasion we walked around the perimeter of the field and I saw, glowing in the late spring, a weed- and grass-strewn path angling out of sight but promising delight if we were to follow it. I wanted to take the path, but Blake said we didn’t have time. Nonetheless, that enduring image has informed many of my ways of thinking about both imagination and a child’s perception.

Aaron’s fantastical canoe trip in the dark is not so different than any of our experiences in life. We are constantly being confronted with the mundanity of wearing a path from work to home, even while our imagination tugs us to one side, begs us to notice the unknown and to live for that exact moment. We think that a successful trip is one which goes in a straight line from goal to goal, but in fact life consists of detours, mystery, annoyances, delight, arduous moments, the light of a fire with friends, rest, and stories. We meet people for a short while before they are gone, but those moments are no less important than the arrival. In fact, the arrival is often a letdown, although hard won and eagerly anticipated. The voyage is the crucial part in the adventure, and arriving is just more taking out the garbage and sweeping the floor after the real show is over.