I once told a colleague that I didn’t believe in objective marking, and she enthusiastically agreed. “I don’t think it’s possible to be objective,” she said.

I told her that I didn’t think we should try to be objective, or even that objectivity is an admirable goal. “The world hasn’t been objective with our students, so we shouldn’t try to pretend there is a level playing field when we are judging their performance.”

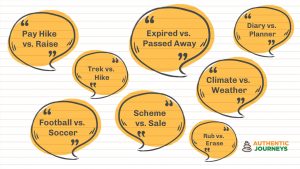

She was puzzled by the assertion, so I told her that I don’t think we can judge the grammar of someone whose first language is English the same as we do someone who learned English as their third language. Likewise, if my student is a single mother from a rural or poverty-stricken background, works a labour job, and takes classes after work, then her situation is very different than the student who has perfect grades because their teachers gave them extra work for extra credit, their parents’ friends hired them for jobs that were useful of their career or finances, and they were able to go to private school and hire tutors to help with their essay rewrites. If my students who work for a living are unfairly targeted by police as people of colour while their  peer is sipping wine with their parents’ colleagues at a private faculty affair, they should hardly be judged the same.

peer is sipping wine with their parents’ colleagues at a private faculty affair, they should hardly be judged the same.

I am stricter in terms of grammar, and expect more literary analysis and understanding of Canadian culture from my domestic private school students, and worry less about deadlines for those whose families are in crisis. I expect my international students to understand more about how an aspect of the text might apply in their own country, to have a better grasp on colonization or western interference overseas, and overlook my domestic French immersion students who fall back into old formatting habits when quoting from our texts.

In terms of ethnic origin, Indian students sometimes use Indian English, since that was perfectly acceptable in some of their schools, Chinese students might forget what pronoun to use but have an excellent grasp of grammar once they are reminded of the rule, while Spanish students prioritize spelling. Nigerian students seem to come from an excellent colonial leftover system, so their writing can be excellent, and indigenous students from Canada are able to make a visceral assessment in how the Canadian justice system works. The domestic student has difficulty with the workings of colonialism, since they have only experienced it as a colonizer, even while they understand perfectly how to apply for funding.

students sometimes use Indian English, since that was perfectly acceptable in some of their schools, Chinese students might forget what pronoun to use but have an excellent grasp of grammar once they are reminded of the rule, while Spanish students prioritize spelling. Nigerian students seem to come from an excellent colonial leftover system, so their writing can be excellent, and indigenous students from Canada are able to make a visceral assessment in how the Canadian justice system works. The domestic student has difficulty with the workings of colonialism, since they have only experienced it as a colonizer, even while they understand perfectly how to apply for funding.

Students with health issues might be expected to skip classes, while those whose spring break was spent examining the archeological sites of ancient Greece on a parent-sponsored holiday should be expected to keep up with their class responsibilities.

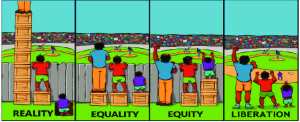

My colleague reluctantly agreed, although I could see the notion was unsettling. She was so accustomed to imagining that we could reduce inequality by applying standard equally that she’d forgotten about equity:

Equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities. Equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome. (Milken Institute School of Public Health).

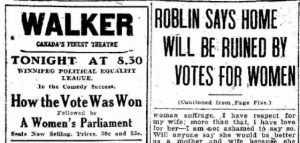

This has been a fraught question in the west for many years, as the grotesque system of slavery was gradually dismantled and other inequalities in western societies began to be debated. Men stood in parliament and discussed whether women should have the vote, while white men installed a series of anti-black laws during the Jim Crow era in the United States. White authorities decided to take away Indigenous children in order to destroy their culture which they viewed as inferior, and Canada worked with the United States to have the notion of cultural genocide removed

Men stood in parliament and discussed whether women should have the vote, while white men installed a series of anti-black laws during the Jim Crow era in the United States. White authorities decided to take away Indigenous children in order to destroy their culture which they viewed as inferior, and Canada worked with the United States to have the notion of cultural genocide removed  from the international definition of genocide. Once white women came into power, they tried to slam the doors on the women of colour who wanted to follow them, much as their own white fingers had been slammed in doors by men, and once all women were assured of their place in power structures they only reluctantly allowed gay people or those living with disabilities to join in their privilege.

from the international definition of genocide. Once white women came into power, they tried to slam the doors on the women of colour who wanted to follow them, much as their own white fingers had been slammed in doors by men, and once all women were assured of their place in power structures they only reluctantly allowed gay people or those living with disabilities to join in their privilege.

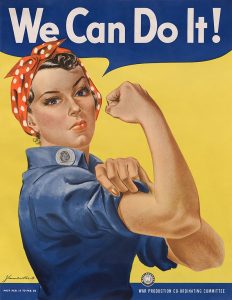

As the early feminist movement made the radical statement that women can do anything a man can do after the first European war opened up jobs for women in factories, that slogan became prominent in the pursuit of universal human rights. The jobs previously presumed to only be possible to be done by men were opened up to women, until even to this day such simplistic notions of equality are enforced and written into policy.

can do after the first European war opened up jobs for women in factories, that slogan became prominent in the pursuit of universal human rights. The jobs previously presumed to only be possible to be done by men were opened up to women, until even to this day such simplistic notions of equality are enforced and written into policy.

Unfortunately, the world is not equitable to begin with, and so those who have traditionally been denied positions, the ability to vote, hold office, or even ride in the front of the bus could not simply be shoved to the front and made to perform. Without access to the Oxford University Library without a male chaperone, Virginia Woolf could hardly be expected to present a seminar on women writers as well as those for whom such barriers didn’t exist.

Society has options when addressing such concerns. They can apply their notion of equality to everyone and if a few marginalized people, who have been systematically barred from knowledge, training, and opportunity, slip through they can congratulate themselves on leveling the playing field. Their rationale for why more people of colour or the differently abled didn’t make the grade will likely be laziness or genetic stupidity. This methodology works to reinforce the same racism, classist, and sexist systems already in existence. Why are there no women doctors, we used to ask, only to discover that women were not allowed into medical school.

Another methodology is more complex. If those in power in the system honestly want to effect change, they can also acknowledge the systemic barriers people like them have placed in the way of the marginalized and then work to overcome that with a targeted equity. If women were denied from studying at a school which has the highest qualifications, then we can accept their equal qualifications from elsewhere. If a person of colour is still improving their English because it is their third or fourth language, then we may safely ignore certain errors when they are speaking or writing without considering them to be a result of stupidity or lack of training.

I had to defend a student’s grade when an email from the Arts faculty at University of Manitoba declared that one of my excellent students who’d been labouring for an A+ the entire term hadn’t earned the grade I had given her. They attached PDFs of two other exams so I could compare. Once I got past the affront to my professionalism, I looked at the other exams just in case I was wrong. I could see, once I looked, where the administrator had been duped. They’d seen awkward phrasing and grammatical problems in my student’s writing and presumed that meant she shouldn’t earn the higher grade. They had fallen into the trap of presuming that because a student’s grammar is weak, or their phrasing awkward, that they do not understand the material.

The other students wrote good exams, but their ideas were a regurgitation of class material. No spelling or punctuation errors marred their writing, but they had contributed nothing other than what I had given them. My A+ student used portions of the story we’d never discussed, connected class material in novel ways, and proved that she knew how to write a paper and had been paying attention in class.

I wrote to the Dean in defense of my grading a letter about how I understood their confusion but that I would not be budging on my grading choices:

I think I can see the Associate Dean’s difficulty now that I look at the exams again. Although my student’s grammar is not perfect, she actually discussed the stories in a much more in-depth fashion, and used examples—such as one of the character’s work in the sex trade—that we did not discuss in class. As well, her essays capture the main thrust of the stories instead of merely citing the way we talked about the stories in class.

I told my students to focus on three things for the exam: essay structure, information from the story that proves their argument, and what we discussed in class in terms of the history of Indigenous people in Canada. She did that well. Although her grammar is not the best, I think I have to stand by my grading.

Fortunately, that was the end of the matter, but the notion stayed with me. I still use it when I talk to my students about their work. There is no reason to judge a student’s ability merely on the basis of grammar—regardless of how easy it is to detect—any more than someone should  judge an astronaut on how well they play cards. The astronaut can learn to play cards in their downtime on the spaceship, and my students will eventually have a better grasp of grammar.

judge an astronaut on how well they play cards. The astronaut can learn to play cards in their downtime on the spaceship, and my students will eventually have a better grasp of grammar.

Although we are makings some progress as a society whose stated aim is equity, there is still a tendency—which is perhaps unconscious on the behalf of those whose own privileged blinds them to the situation of others—to re-establish ancient systems of oppression. When Colleen was taking an English honours class in my department, her professor insisted on dividing the small class into two groups. Although I’m not sure we can call this deliberate, she divided the class into two groups along ethnic lines. Perhaps in her mind it made sense to separate the  Asians and the whites, but she wasn’t considering either the optics or implicit racism of her decision. When Colleen asked her peers in the class if they’d noticed, people of colour had unanimously noticed. The whites were accustomed to ignoring how racial lines were still being used to divide people and said they thought it was a random error.

Asians and the whites, but she wasn’t considering either the optics or implicit racism of her decision. When Colleen asked her peers in the class if they’d noticed, people of colour had unanimously noticed. The whites were accustomed to ignoring how racial lines were still being used to divide people and said they thought it was a random error.

At a recent competition for best three-minute Master’s thesis presentation, fourteen of the eighteen presenters were international students. The remaining four were white domestic students. Out of the four prizes given, three prizes went to the whites. While I think the audience could agree on one of the selections, the one awarded to a professional older woman competing with new Master’s students, but her receiving the second prize stood out, at least in the row where I was sitting. She earned three thousand dollars in total, and the white woman who won the next prize—which amounted to a few hundred dollars—gave a quite bland presentation. To be fair, some of the international students’ presentations were too jargon-filled and specialized to understand easily, while others had accents and a facility with the language which made them difficult to comprehend. That didn’t represent the work the rest of them had done, however.

One presentation in particular, about the effect of colonization and capitalism on the traditional muslin industry of Bangladesh was clever, witty, and wide-ranging. Its presenter was relaxed, coherent, and her project sounded interesting. Four people I spoke to after the presentations were judged said they thought that was one of the best, although lost out to the white women. Another Indian woman gave a presentation on lake water remediation and phosphorous runoff from agricultural fields that showed promising research, and outlined the problems with the current system and how her research was meant to investigate alternatives.

The lone prize which went to a person of colour was that given to a man who had a lot of friends in the room. He won the prize for audience choice, which showed the audience either didn’t agree with the prizes that were to be given when they were voting, or merely liked the man. His presentation about brown bat hibernation was well done, thorough, and well put together. Another man, who was also white, gave an excellent presentation on media representations of manufactured events and responses. Although he didn’t win any awards, the four people I talked to thought he did an excellent job as well.

I think the judges—three white people from industry and the dean’s office—weren’t entirely aware that they were judging coherence based on the ability to understand an accent or follow the presentation about arcane material. They likely thought they were judging the completion on the basis of equal standards, although I would argue that such a stance is by its nature unequal. The international students can hardly be blamed that they learned English later in life and the flow of their language doesn’t match a local, which means that the criteria should be shifted to take content more into account. It doesn’t mean a free ride for someone who is less qualified—which is what we hear from racists all the time about equal hiring practices—but rather that we focus on aspects of the performance which matter and less so on those which are cosmetic.

This is perhaps easier to see—here in the west at least—when we consider the accommodations offered by accessibility services at my university. Their premise is  that once the barriers to learning are swept away for students who have a disability which affects their performance, then the playing field is leveled. They provide interpreters for students who are hard of hearing, note-takers for those with learning disabilities or physical barriers, and quiet, monitored places to write exams for those who require a distraction-free environment. They have staff who can rephrase questions, provide extra time on assignments for students with anxiety or chronic illnesses, and counselors for those with mental illness.

that once the barriers to learning are swept away for students who have a disability which affects their performance, then the playing field is leveled. They provide interpreters for students who are hard of hearing, note-takers for those with learning disabilities or physical barriers, and quiet, monitored places to write exams for those who require a distraction-free environment. They have staff who can rephrase questions, provide extra time on assignments for students with anxiety or chronic illnesses, and counselors for those with mental illness.

Although that sounds as though the university is giving some students benefits that not everyone receives—and therefore is not equality—it’s worth considering that a wheelchair is not a benefit for someone who can walk. It allows someone who cannot walk to enjoy some of the same privileges as other students, but in no way compensates for the fact that their disability means they  have to struggle in an abled world in order to compete with those who not only do not realize what their disability means, but who also might have an unadmitted prejudice which means they have to be better in order to win the same prize.

have to struggle in an abled world in order to compete with those who not only do not realize what their disability means, but who also might have an unadmitted prejudice which means they have to be better in order to win the same prize.

Ultimately, the decisions we make today either can further install age-old inequalities in an unfair system, or we can take the opportunity to make sure that everyone has an equal seat at the table. The resultant society is one in which we will be unable to distinguish equality from equity, and although we are far from that moment now, it’s worth striving for that desirable goal.