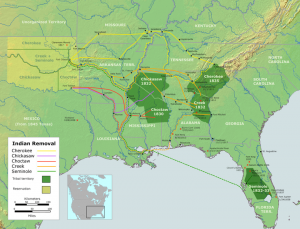

Fifty percent of the Choctaw people had only just survived the forced relocation from Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana into Oklahoma (the aptly named Trail of Tears),  when a member of the tribe heard about An Gorta Mór, the great famine in Ireland. Despite barely being able to provide for themselves in the barren land of Oklahoma, the Choctaw of Skullyville and the Choctaw of Doaksville donated three hundred and twenty dollars, or the equivalent of five thousand dollars today.

when a member of the tribe heard about An Gorta Mór, the great famine in Ireland. Despite barely being able to provide for themselves in the barren land of Oklahoma, the Choctaw of Skullyville and the Choctaw of Doaksville donated three hundred and twenty dollars, or the equivalent of five thousand dollars today.

Perhaps because they were both oppressed by their colonial governments, both communities felt a kinship. The British had starved the Irish in order to take the cash crops for sale, and if the Irish refused, they would lose their land and future livelihood for arrears. The Choctaw had endured the forced relocation because European settlers, some of them Irish in fact, were taking over their land, and they were offered the chance to leave or be murdered outright. Perhaps because the Choctaw had so recently endured their own starvation that they didn’t want to wish that on another.

felt a kinship. The British had starved the Irish in order to take the cash crops for sale, and if the Irish refused, they would lose their land and future livelihood for arrears. The Choctaw had endured the forced relocation because European settlers, some of them Irish in fact, were taking over their land, and they were offered the chance to leave or be murdered outright. Perhaps because the Choctaw had so recently endured their own starvation that they didn’t want to wish that on another.

Whatever the emotional motivation, the gift resonated through the centuries. When the various nations in the South West were suffering under the yoke of Covid in 2020, and their federal government had abandoned them yet again, they reached out online. Once the Irish people found out that a fundraising effort had been launched, thousands of ordinary Irish people donated. The Choctaw gift had been famous in Ireland, and even nearly two hundred years later hadn’t been forgotten. Now that the cousins of the Choctaw, the Navajo and Hopi peoples were similarly being ignored by their colonial government in their time of need, the Irish gave back. Over four million dollars were raised, with hundreds of thousands coming from Ireland.

The two nations had met before, especially in the 1990s, such as when they both attended each other’s memorial walks which commemorate the memory of their respective peoples who died on the forced march, for the Choctaw, and the protest made by the Irish in 1848. State visits have continued since, and in 2017 a stainless steel sculpture of nine twenty-foot eagle feathers was set up in Bailick Park, Midleton, County Cork to acknowledge and thank the Choctaw Nation for their donation.

‘Kindred Spirits’ Sculpture, Cork, Ireland

A tribute to the incredible generosity the Choctaw Nation showed the Irish people during the Great Famine.

In September, 2020, the Iroquois National Lacrosse Team had not been invited to the tournament because organizers refused to recognize them as a Sovereign Nation. A particularly damning decision considering that not a single Indigenous team would be present for a game which is indigenous in origin. Once the reluctant decision was made to include them, the organizers claimed there was no longer a spot, thus effectively denying them again. In a show of solidarity and moral justice, the Irish National Lacrosse team gave up their spot so that the Indigenous players might compete.

In these dark days when the western  colonial world has become cheerleaders for a genocide in Gaza while the same historical policies are visited upon the Palestinians, it’s worth remembering that in the past we made other choices. We do not need to be counted amongst those who didn’t care while a people were starved.

colonial world has become cheerleaders for a genocide in Gaza while the same historical policies are visited upon the Palestinians, it’s worth remembering that in the past we made other choices. We do not need to be counted amongst those who didn’t care while a people were starved.

Let us not be like Charles Trevelyan, who administered the British government’s food aid programme. He said that “The judgement of God send the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson and that calamity must not be too mitigated [..] The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.”

Let us instead imitate the Choctaw people, who despite suffering greatly at the hands of the same colonizer greedy  for their land, reached out when they saw another group of people starving. Their selfless action created a bond between nations that over a hundred years of colonial rule has not broken, and wrote a new chapter for the human species that we would be wise to remember and emulate.

for their land, reached out when they saw another group of people starving. Their selfless action created a bond between nations that over a hundred years of colonial rule has not broken, and wrote a new chapter for the human species that we would be wise to remember and emulate.