When William Golding imagines his feral  schoolboys in Lord of the Flies, he thinks that they will inevitably shed the shallow indoctrination of the arbitrary and recently acquired rules of polite society and fall back upon their baser instincts which call them to attack each other. Like prisoners who weren’t lucky enough to have Jeremy Bentham design their panopticon prison, they run amuck without legalistic oversight, and the death of their friend is, in Golding’s terms, the natural result.

schoolboys in Lord of the Flies, he thinks that they will inevitably shed the shallow indoctrination of the arbitrary and recently acquired rules of polite society and fall back upon their baser instincts which call them to attack each other. Like prisoners who weren’t lucky enough to have Jeremy Bentham design their panopticon prison, they run amuck without legalistic oversight, and the death of their friend is, in Golding’s terms, the natural result.

This view of civilization as a set of chafing rules and feared punishments informs much of our way of thinking about society in the west. If we have a Purge night, like the popular movie argued, then people will turn into berserkers. A loss of  infrastructure and civil society in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road converts nearly everyone into an inarticulate cannibal hungry for human meat. The zombie shows and movies franchises are premised on the desire to kill the uninfected, for the death of mindless zombies quickly grows old for an audience who wants real risk and consequences. The message is clear, in the struggle for survival, civil society, comradery, gratitude, and generosity, are the first causalities.

infrastructure and civil society in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road converts nearly everyone into an inarticulate cannibal hungry for human meat. The zombie shows and movies franchises are premised on the desire to kill the uninfected, for the death of mindless zombies quickly grows old for an audience who wants real risk and consequences. The message is clear, in the struggle for survival, civil society, comradery, gratitude, and generosity, are the first causalities.

The corollary to this, that humanity is a “fallen” species, in the Christian sense, is to put the blame squarely on our nature. This is a convenient fantasy for those who harbour their own nasty impulses and desires and would like to imagine that all  others are the same. In a world that brought us the Rwandan genocide, so goes the argument, any chicanery and evil is possible, for we cannot escape our base impulses. In an effort to lessen their own moral burden such pundits point to the inevitable nature of their own immorality; to believe otherwise makes them culpable for their behaviour.

others are the same. In a world that brought us the Rwandan genocide, so goes the argument, any chicanery and evil is possible, for we cannot escape our base impulses. In an effort to lessen their own moral burden such pundits point to the inevitable nature of their own immorality; to believe otherwise makes them culpable for their behaviour.

I believe that this mercenary way of thinking about humanity is deeply flawed, at least partially because it is not true. For every story of someone taking advantage during an emergency, there are a hundred where people have been generous to neighbours and friends, have reached out to help a stranger, and tried to ensure that the bonds of society are maintained and strengthened. To use some American examples, since this way of thinking has become the daily bread of American media, it’s worth remembering that disasters on a smaller scale have occurred, and the inarticulate cannibals did not appear. The World Trade Centre bombing of 2001, the electrical blackout of 2003, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Sandy in 2012, are good examples of what actually happens in an emergency. In all of those cases, the anticipated widespread looting turned out to be a myth. There were no little streets hurling themselves upon the great.

The World Trade Centre bombing stranded hundreds of people in Gander, Newfoundland, once the American airspace was declared off limits to their own people for fear of attack.  The flights were diverted to Canada—where, presumably no one cared if they were bombed—and locals opened their homes and gave those stranded a place to stay. They did this in Halifax when the Vietnamese boat people landed on their shores, and if the government hadn’t gotten their hands on the Chinese migrants first, I am sure people in Vancouver would have done the same for those who arrived half-dead in shipping containers.

The flights were diverted to Canada—where, presumably no one cared if they were bombed—and locals opened their homes and gave those stranded a place to stay. They did this in Halifax when the Vietnamese boat people landed on their shores, and if the government hadn’t gotten their hands on the Chinese migrants first, I am sure people in Vancouver would have done the same for those who arrived half-dead in shipping containers.

Instead of widespread violence during the blackout of 2003, commuters walking home stopped to volunteer as street signals in Toronto once they saw the snarl of traffic. They worked for hours, and when they were too tired to continue, they beckoned to others to take over. Traffic kept flowing, and restaurateurs who still had power were assisted by diners when they became too busy to cope with the rush. Although 50 million people lost power for up to two days and at least eleven people died, the ravening cannibals did not appear. Instead, public buildings were opened to stranded commuters, and hospital staff worked in the half-light of generators to deliver babies and deliver care.

When Hurricane Katrina tore into New Orleans, breaking the levees and killing 1,800 people, hundreds of volunteers in three or four hundred boats rescued more than ten thousand people stranded by the floodwaters. A Canadian team of urban rescue volunteers climbed aboard flights and were in New Orleans a few hours later, and when they were asked how they arrived, they merely said they’d bought tickets. One Walmart employee risked her job to smash a loader through the walls of her flooded store, so that she could give away essential goods for those who had lost everything.

into New Orleans, breaking the levees and killing 1,800 people, hundreds of volunteers in three or four hundred boats rescued more than ten thousand people stranded by the floodwaters. A Canadian team of urban rescue volunteers climbed aboard flights and were in New Orleans a few hours later, and when they were asked how they arrived, they merely said they’d bought tickets. One Walmart employee risked her job to smash a loader through the walls of her flooded store, so that she could give away essential goods for those who had lost everything.

During Hurricane Sandy, people with power ran cords to their front gate for others to charge their devices, restaurants and bars in New York sent loads of food to New Jersey, and one doctor offered free medical care—which is both anomalous and particularly generous in the United States, which charges outrageous fees for even a doctor visit.

ran cords to their front gate for others to charge their devices, restaurants and bars in New York sent loads of food to New Jersey, and one doctor offered free medical care—which is both anomalous and particularly generous in the United States, which charges outrageous fees for even a doctor visit.

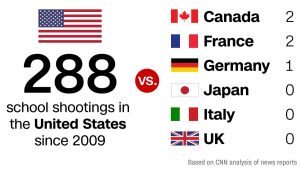

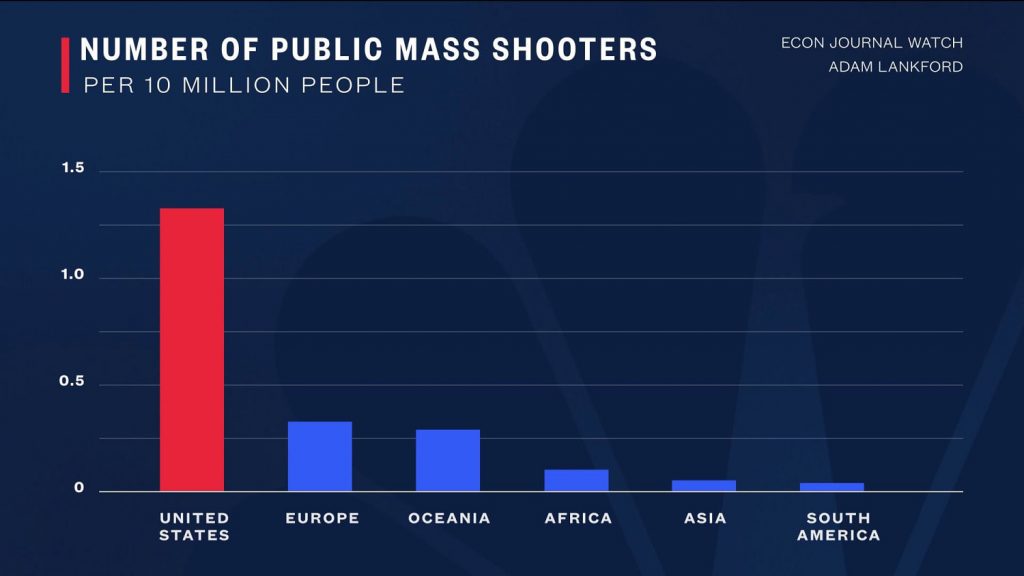

The main problem with the cannibal horde way of thinking about humanity in crisis is not only that such ugly ideologies of a rapacious humanity are unsupported by evidence, but that they might come to pass if the ideology gains traction in broader society. That is especially a problem in the United States, which has a significant percentage of the population that is both traumatized and trained to react to privation or an existential threat with violence.

The United States has more people in the military and in prison per capita than any other country. Although that is scarcely a point of pride, it does beg a profoundly disturbing question: what is the effect of this on society?

Although I have spent some time above on the ravening hordes which I do not believe fill the streets when a disaster strikes, I am intrigued that so little thought is put into how such a statistic about the amount of people in the military or in prisons might affect society.

Many people can see that having a  huge army might be an incentive to use it in wars, and that with that many people in prison and effectively living off government money, that mercenary corporations will most certainly take an interest and try to boost prison populations. There is even more incentive to boost those populations with amendment 13, which allows corporations to take advantage of prisoner slave labour. On the surface of it, the amendment sounds positive, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States,”

huge army might be an incentive to use it in wars, and that with that many people in prison and effectively living off government money, that mercenary corporations will most certainly take an interest and try to boost prison populations. There is even more incentive to boost those populations with amendment 13, which allows corporations to take advantage of prisoner slave labour. On the surface of it, the amendment sounds positive, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States,”  although the discerning reader quickly becomes aware of the “except.” We rarely pause to think about what happens to those people once they are released into the wild.

although the discerning reader quickly becomes aware of the “except.” We rarely pause to think about what happens to those people once they are released into the wild.

The United States’ active military personnel amount to 1,390,000 people. That is seemingly overshadowed only by the Chinese and Indian armies, at 2 million and 1.5 million respectively, but once those numbers are divided by population, however, a different story emerges. Those in active military service in the US make up .42% of the population, while in China it is .142% of their population of 1.412 billion, and in India it amounts to .1% of 1.393 billion people. This immense army, at least in relative terms, does more than eat through American financial resources. It also means that at any given time there are many people trained in violence as well as suffering from some form of trauma in broader American society.

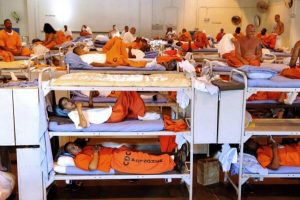

Slightly more people are in prison at any given time in the US, which is 1,675,400, or .5% of the population. According to the Pew Institute, 7% of the current American population have served, and Ehrlich Law offices declare that 3% of the  population have been incarcerated at some point. At any given time, at least ten percent of American citizens experienced the dehumanizing and often traumatic circumstances of either militarization or incarceration. That is a huge percentage of possibly traumatized people walking around in society.

population have been incarcerated at some point. At any given time, at least ten percent of American citizens experienced the dehumanizing and often traumatic circumstances of either militarization or incarceration. That is a huge percentage of possibly traumatized people walking around in society.

This perhaps explains the statistic from the National Institute for Mental Health that lists 21% of the population as registering with a mental illness, at least in terms of doctor’s diagnosis. While those with a serious mental illness amounted to 5.6% of the population, it still remains a significant number.

Some would argue that the military is not necessarily traumatizing, although that view would have to ignore the fact that the military, as a matter of policy, deliberately traumatizes its soldiery in boot camp in order to break them down and make them follow orders. Likewise, although some prison sentences might be short as they are a punishment for minor crimes, they are served in the company of many people who we have declared as a society should not be allowed to socialize with us. That means that someone who has been in prison has been traumatized in a state-sanctioned system like the military, although the goal in prisons is a punishment model rather than training. Unlike the military person, the training of the convict is inadvertent. The ex-convict leaves the system to suffer similar discrimination outside the prison which matches his or her experience inside, and that burden of trauma is not even acknowledged by society let alone treated medically or otherwise.

might be short as they are a punishment for minor crimes, they are served in the company of many people who we have declared as a society should not be allowed to socialize with us. That means that someone who has been in prison has been traumatized in a state-sanctioned system like the military, although the goal in prisons is a punishment model rather than training. Unlike the military person, the training of the convict is inadvertent. The ex-convict leaves the system to suffer similar discrimination outside the prison which matches his or her experience inside, and that burden of trauma is not even acknowledged by society let alone treated medically or otherwise.

In the case of the military, many people presuppose that the military knows what it is doing to the impressionable soldiers in its care, while in prison, no one really cares  what happens to criminals. Society has already decided they are not worth worrying about, and therefore little attention is paid to making prisons safer or healthier mentally, let alone rehabilitating them so that they might become productive members of society. For one thing, the private prison system needs fodder for the machine, and that is necessarily predicated on a steady diet of criminals. Having such foxes guard the henhouses, in the form of asking a for-profit prison system manage the rehabilitation of the prisoners, is meant to fail.

what happens to criminals. Society has already decided they are not worth worrying about, and therefore little attention is paid to making prisons safer or healthier mentally, let alone rehabilitating them so that they might become productive members of society. For one thing, the private prison system needs fodder for the machine, and that is necessarily predicated on a steady diet of criminals. Having such foxes guard the henhouses, in the form of asking a for-profit prison system manage the rehabilitation of the prisoners, is meant to fail.

When we think about soldiery we imagine someone risking their life to save us, to defeat an enemy of our family, and we think about them as a hero. We picture them coming back from war hardened, solidified, as though, by dint of their experiences, they’d become a more stable person than when they left. When we imagine those in one of our many prisons we think of them as being punished. The television in the common room, the access to books and playing cards are seen as unnecessarily luxurious, when we think they should have been brutalized.

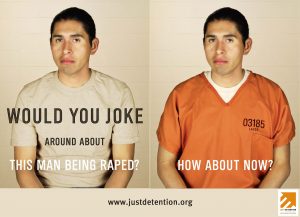

We have a sneaking suspicion, which is based in real reports as well as movies, that they are mistreated by fellow prisoners, and in our hardened hearts we greet that news with glee. They should be punished, and thus prison rape becomes a stock joke for comedians and commentators, and a grim reality which is poorly controlled in the prison system itself. In fact, by ignoring the incidence of prison rape, the system tacitly allows it, and by ignoring the returning soldier’s mental state, we are complicit in the fall-out of their damage to society.

with glee. They should be punished, and thus prison rape becomes a stock joke for comedians and commentators, and a grim reality which is poorly controlled in the prison system itself. In fact, by ignoring the incidence of prison rape, the system tacitly allows it, and by ignoring the returning soldier’s mental state, we are complicit in the fall-out of their damage to society.

It’s worth considering what soldiers and prisoners have in common, for they have both endured hardship and likely suffer from PTSD. Some might say that the criminals deserve the trauma and that the soldiers signed up for it. Those claims ignore several factors, however. Not surprisingly, both soldiers and criminals tend to be from the poorer classes, and sign up or commit crime out of desperation. Therefore they cannot be said to have chosen what has happened to them, exactly.

and prisoners have in common, for they have both endured hardship and likely suffer from PTSD. Some might say that the criminals deserve the trauma and that the soldiers signed up for it. Those claims ignore several factors, however. Not surprisingly, both soldiers and criminals tend to be from the poorer classes, and sign up or commit crime out of desperation. Therefore they cannot be said to have chosen what has happened to them, exactly.

As well, and this is much more important, we have to wonder about what effect traumatized soldiers and ex-cons have on society instead of worrying about who is at fault and what people deserve. This is a broader question about what we want as a society. When the soldiers return from either killing people or people trying to kill them, they are understandably brutalized. Likewise, the criminal who has served their time is accompanied by their own PTSD. Neither soldiers nor criminals are supplied with counselling, and so both parties, unless they take on the task themselves, are thrown into the streets with their lingering trauma and inability to cope.

It’s worth pondering what such an influx of potentially damaged people can do to a society, whatever the reasons they were incarcerated or signed up.  When a group of people we have abused, who have been violent to others whether that was sanctioned or not, are released into broader society they bring all of that violence and lack of emotional regulation with them. They then can abuse their family members, neighbours, and coworkers as well as themselves. They become an infection that can destroy a society. Without proper rehabilitation for former inmates, counseling and mental health work for former soldiers, then we risk the destruction of society as a whole.

When a group of people we have abused, who have been violent to others whether that was sanctioned or not, are released into broader society they bring all of that violence and lack of emotional regulation with them. They then can abuse their family members, neighbours, and coworkers as well as themselves. They become an infection that can destroy a society. Without proper rehabilitation for former inmates, counseling and mental health work for former soldiers, then we risk the destruction of society as a whole.

Some would say that we cannot afford to coddle prisoners, and that soldiers need to toughen up, but they are not considering the true cost to broader society. The violence which  has been enacted upon those two groups was already in service of the myth that money is more important than human life, and that’s how many of them became soldiers or criminals. For a pittance of the amount that we would spend mitigating their actions once freed from their constraints, we might be able to prevent the damage they are going to do to their communities.

has been enacted upon those two groups was already in service of the myth that money is more important than human life, and that’s how many of them became soldiers or criminals. For a pittance of the amount that we would spend mitigating their actions once freed from their constraints, we might be able to prevent the damage they are going to do to their communities.

These preventative measures would be a form of self-protection. We need to consider how those damaged people will become a cancer in the body politic, and therefore take measures to mitigate that before spending even more money building larger prisons and imprisoning both soldiers and former inmates. Without supports in the society, they may both end up in the same place, and from there perpetuate the misfortunes which led them there in the first place. In the end, we, even if we have never served or been incarcerated, are the ones who lose. The world outside the prison and the barracks begins to resemble that within, as we ignore the plight of our fellow citizens and they respond to that indifference in the way that they have been taught.