Most of our cities, however hostile to animal life, have some hardy species who survive and even thrive amongst us. Perhaps the cockroach, mice and rats come immediately to mind, and then after a moment’s reflection, the raccoon and squirrel, pigeon and seagull. Although we seldom pause in our busy urban lives to reflect on the cultural changes those animals have undergone to live amongst us, we usually notice when the raccoons infest the attic, or a foreign student or tourist takes a photo of an animal we rarely pay attention to. If we ignore them, we think even less about what it means to be a human animal living in our cities. Other than the anthropologist and sociologist, few people consider what cultural shifts we have undergone as a species, or what coping strategies we employ as individuals.

The draw for both human and non-human animal to the urban environment is firstly food. Humans come to the cities around the globe because corporate agriculture has starved them out of agrarian jobs and those animals who can more easily adapt to us have learned to pick through garbage and live in chimneys.

The squirrel has learned that many humans put out food for birds, or—from the squirrel’s point of view—for them, and accordingly reaches into canisters on sticks in backyards all over North America. Likely they accept our irate expostulations as a matter of course, or dinnertime entertainment. The pigeon, which feeds on grains we spill from transport, can also easily leave the granaries and fields near the city for the enticement of old people in the park with bread crumbs and litterers throwing hamburger buns and French fries from windows.

view—for them, and accordingly reaches into canisters on sticks in backyards all over North America. Likely they accept our irate expostulations as a matter of course, or dinnertime entertainment. The pigeon, which feeds on grains we spill from transport, can also easily leave the granaries and fields near the city for the enticement of old people in the park with bread crumbs and litterers throwing hamburger buns and French fries from windows.

The raccoon  has learned Houdini like skills when opening trash bins, and employs those in the fall when seeking haven from the winter. Their more traditional homes that are burrows taken over from other animals or the hollow boles of ancient trees, have been destroyed when we clear-cut the forest into concrete and tarmac, but the hardy raccoon is not disconcerted. They merely adapt to what is available. Rats and mice nest in our insulation as though it were produced for the comforting purpose, and typically frequent the too large holes plumbers drill to allow pipes and electrical fittings entrance through the wall.

has learned Houdini like skills when opening trash bins, and employs those in the fall when seeking haven from the winter. Their more traditional homes that are burrows taken over from other animals or the hollow boles of ancient trees, have been destroyed when we clear-cut the forest into concrete and tarmac, but the hardy raccoon is not disconcerted. They merely adapt to what is available. Rats and mice nest in our insulation as though it were produced for the comforting purpose, and typically frequent the too large holes plumbers drill to allow pipes and electrical fittings entrance through the wall.

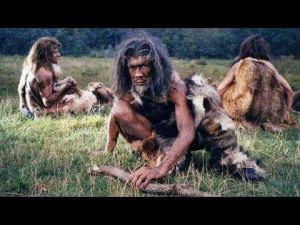

The human animal is in a similar situation. We were adapted for many different environments around the world, but few of them were urban. We have been agrarian for only ten to twelve thousand years, but most of the preceding hundreds of thousands of years we were hunter gatherers. We learned what was safe to eat, what near poisons we could use as medicine or for recreation, and how to fashion our homes from materials as diverse as dung and mud to wood and stone. Certain of our predilections have  remained stable, however. We spent much of our time eating and socializing, building our own homes and making our own clothing, and learning the whims and habits of less than a hundred people.

remained stable, however. We spent much of our time eating and socializing, building our own homes and making our own clothing, and learning the whims and habits of less than a hundred people.

Moving to the city has meant that we have had to modify some of those habits, or at least modify our interactions with the city in order to allow behaviours we have followed for centuries and are not yet prepared to replace by television or Facebook. We can no longer build our own homes, and therefore have lost much of the satisfaction that comes from that, and instead we become, as Thoreau claimed over a hundred years ago, “the ninth part of a man.”

We rely on others to build our home, others still to run wiring, plumbers to put in the pipes, and still others to paint. The last strivings of this sort that are left are found in those who wander the aisles of Home Depot and Rona, searching through the raw materials with which to make their mark on prefabricated houses. Because as a society we don’t know our builders well enough to trust them, we have a system in place, city inspectors, who ensure the jobs are done properly. We are so far from being able to build our own house that we don’t even know it is done well when it happens in front of our dumfounded faces. When people find out someone could build, wire and plumb a cabin in the woods on their own, they are shocked, although humanity did that until recently and in many places in the world, are still able to.

Having lost the joy of our craft of hand, we moved inside to weaving, painting, making music, and sculpting. Those skills as well are increasingly fading, perhaps because we compare ourselves with the many more talented people online and find ourselves wanting. Perhaps also, the urban life demands much of our time, and we spend hours running around the city in order to satisfy some obscure material demand. We have no time or energy, after giving so many hours to the boss, that we can afford some to improve ourselves.

inside to weaving, painting, making music, and sculpting. Those skills as well are increasingly fading, perhaps because we compare ourselves with the many more talented people online and find ourselves wanting. Perhaps also, the urban life demands much of our time, and we spend hours running around the city in order to satisfy some obscure material demand. We have no time or energy, after giving so many hours to the boss, that we can afford some to improve ourselves.

Our food collection skills have also atrophied. Most of us know someone who collects their own wild mushrooms, but at one time that was not something we would have exclaimed  over. Food selection is dependent on trips to massive grocers, who have chosen for their own pecuniary purposes what tomato lasts longest on the shelf, what peppers should come to market, and what foods we will never see or know about. We do not know what is available even in our local environment, but we are so cut off from our ideas about food that many city children do not know the connection between pork and pigs, and beef and cows. Like our atrophied house building skills, we rely on systems we have put in place to protect us from unscrupulous proprietors while at one time we would have known the neighbour well enough to protect ourselves. We scrutinize expiry dates and ingredients lists where once we crept up on unsuspecting hazelnuts hanging from the tree in our yard.

over. Food selection is dependent on trips to massive grocers, who have chosen for their own pecuniary purposes what tomato lasts longest on the shelf, what peppers should come to market, and what foods we will never see or know about. We do not know what is available even in our local environment, but we are so cut off from our ideas about food that many city children do not know the connection between pork and pigs, and beef and cows. Like our atrophied house building skills, we rely on systems we have put in place to protect us from unscrupulous proprietors while at one time we would have known the neighbour well enough to protect ourselves. We scrutinize expiry dates and ingredients lists where once we crept up on unsuspecting hazelnuts hanging from the tree in our yard.

Our ability to make our own clothes has become the ability to shop, where some brag about bargains and others about fashion. I once sat with some friends in Vancouver and chatted while one member of the household fashioned a shirt on a sewing machine. When she held up the finished product and everyone cheered at her accomplishment, I was aghast. She had fashioned what I would be generous to call a pillowcase with holes for arms and a head. The garment—and I use that word as loosely as hers fit—was merely two pieces of cloth sewn together. She made no attempt to accommodate the infuriating curves and bumps of the human form. The applause of her admirers was as dismaying as the result of her labour. The rest of the room also had no idea how to make a shirt, I presumed, and could not even measure her ungainly product against that made by a machine.

Some people are relearning these skills, albeit in the new context. Lars Eighner talked about the skills acquired learning to dumpster dive and some people are eschewing the big box stores and thrifting, or even quilting, knitting, and teasing a shape from fabric and a sewing machine, but whether those people are in the minority it might be too soon to suppose. Dumpstering furniture might be the new version of making it, while shopping in the health food store might replace the bounty of the woods.

Some of those people who are developing survival skills are like the animals that live on the outskirts of human  habitation. They hunt between the motorways, and gather woodland plants beside the railway lines, dumpster food, and attend talks where free food is to be found. These people—and the largest group would be made up of the very poor—walk through the new environment differently.

habitation. They hunt between the motorways, and gather woodland plants beside the railway lines, dumpster food, and attend talks where free food is to be found. These people—and the largest group would be made up of the very poor—walk through the new environment differently.

In terms of a million years of human habitation, they walk as if they are still in the forest, they watch where they step and walk on the balls of their feet. They make no sound at all, and are dismayed that some are frightened when they suddenly appear behind them. To forestall this, they deliberately shuffle their feet so others won’t be fearful. They pass, barely, as urban dwellers, but when they look in shop windows ahead of them as if they are glancing over their shoulder, listen for the grate of a shoe behind them to detect the size and speed of their follower, and take a deep breath through their nose upon exiting an elevator so they can smell if someone is waiting in the hallway, then they give themselves away.