The terrible truth that Steve Cutts reveals in his short animated film “Happiness” is that consumerism entices but does not lead to happiness. His rats are surrounded by consumer messages that promise that they—even the main rat character—will be happy if he merely buys the product, but each time the rat believes in the message he is betrayed and becomes even more unhappy than ever.

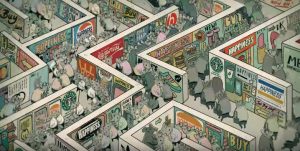

The thousands of rats in Cutts’ film are surrounded by advertisements. The hordes of rats in office clothes that make up the citizens in their crowded city, are hemmed in on every side by an advertising that promises each of their products will deliver delight.  Each of the rats, most importantly the main rat we follow in the film, are convinced enough by these messages that they avidly pursue each promise. Perhaps because he is trapped in a maze of billboards and ads, our leading rat follows others and buys a pile of products only to throw them away when more products are in front of him. He pushes in with his fellow rats on black Friday and then fights with

Each of the rats, most importantly the main rat we follow in the film, are convinced enough by these messages that they avidly pursue each promise. Perhaps because he is trapped in a maze of billboards and ads, our leading rat follows others and buys a pile of products only to throw them away when more products are in front of him. He pushes in with his fellow rats on black Friday and then fights with  his fellow shoppers until some have lost their limbs and blood covers the walls. The ads’ promise of happiness is so convincing that even this experience does not change his mind and soon he is driving a convertible

his fellow shoppers until some have lost their limbs and blood covers the walls. The ads’ promise of happiness is so convincing that even this experience does not change his mind and soon he is driving a convertible  until he stalls in traffic with thousands of others, his brief joy turning to morose misery as his car is vandalized and it begins to rain. The promise of happiness in the form of an alcohol ad on a billboard

until he stalls in traffic with thousands of others, his brief joy turning to morose misery as his car is vandalized and it begins to rain. The promise of happiness in the form of an alcohol ad on a billboard  leads him to his next pursuit and soon he is drunken and seeking a flyer’s promise of happiness in the form of prescription medication. Once this promise is broken, he is destitute but still pursuing the consumer promise of a hundred dollar bill which takes him to a factory workplace where he is trapped by his wish for money enough to endure the misery of his job.

leads him to his next pursuit and soon he is drunken and seeking a flyer’s promise of happiness in the form of prescription medication. Once this promise is broken, he is destitute but still pursuing the consumer promise of a hundred dollar bill which takes him to a factory workplace where he is trapped by his wish for money enough to endure the misery of his job.

As the litany of the rats’ attempt to pursue happiness implies, each time he tries to fulfill the promise offered, he is betrayed by the ultimate emptiness of the promise. He believes consumerism will lead him to enjoyment, but he merely ends biting his fellow rats over a big screen television. He believes that the car will offer him the freedom and success of the car ads, but the traffic of the city defeats that possibility and the liquor he embraces as the film nears its end merely symbolizes his desperation. The cycle of consumerism and misery the rat is confined by is  symbolized by the images of entrapment, such as the maze of ads, the claustrophobia of the commuter train, the anger of the confining angry crowds on black Friday, but the rats’ misery becomes more apparent when he

symbolized by the images of entrapment, such as the maze of ads, the claustrophobia of the commuter train, the anger of the confining angry crowds on black Friday, but the rats’ misery becomes more apparent when he  resorts to alcohol and ultimately drugs. The prescription medications, we learn in the film, do not remove the cause

resorts to alcohol and ultimately drugs. The prescription medications, we learn in the film, do not remove the cause  of his misery, but rather mask it with yet another portrayal of happiness: the Disney castle of fantasy. This fantasy does not endure, and before long the rat falls into the street with other destitute rats. There a chance hundred dollar bill, with its similar promise of ultimate happiness, leads him to the terrible image of an office job.

of his misery, but rather mask it with yet another portrayal of happiness: the Disney castle of fantasy. This fantasy does not endure, and before long the rat falls into the street with other destitute rats. There a chance hundred dollar bill, with its similar promise of ultimate happiness, leads him to the terrible image of an office job.  The rat trap clamps down on his neck as he reaches for money and his unending misery—which has been implied by his pursuit of consumer goods—is assured as he types with a million others.

The rat trap clamps down on his neck as he reaches for money and his unending misery—which has been implied by his pursuit of consumer goods—is assured as he types with a million others.

Although Cutts’ rat seems to be happy enough as the film starts—in that he is free to pursue what he wishes—his chase after the consumer goods from the ads which promise happiness merely ensures that he will be trapped chasing after money and the trash that money can buy. Ultimately, he is as trapped as all the other rats in a cycle of buying, throwing away, and suffering for money. Although Cutts does not offer an alternative to the promised lifestyle of our society, his unflinching portrayal does little to make rampant consumerism look inviting. Instead he offers the argument that consumerism is a trap into which we willingly walk and will lead us to misery.