Now that Covid-19 has been with us for two years, its profound effects on the different societies of the planet are  becoming more obvious. Relatively democratic societies, for all their flirtation with fascism, are descending into mob rule as unscrupulous would-be politicians use public health mandates to claim that society is falling into a kind of communist chaos. Massive riots have erupted at the suggestion that people need to be vaccinated to eat in a restaurant, or that they should avoid crowds so that the latest variants are not passed around as quickly. Western societies have stooped to offering lottery tickets or even hundred dollar vouchers for those reluctant enough to have avoided the vaccine rollout, hoping to encourage them by carrot, and when that fails, by the stick of fines and restrictions on movement. As well, our fantasy that colonial ways of thinking were relegated to history has been undermined by the fact that the west ensured that they had the vaccine first, and the developing world be damned. Even as people in developing nations are crying out for access to the vaccine, in the west they ensure their people survive by hoarding nearly the entire production of the various vaccine companies.

becoming more obvious. Relatively democratic societies, for all their flirtation with fascism, are descending into mob rule as unscrupulous would-be politicians use public health mandates to claim that society is falling into a kind of communist chaos. Massive riots have erupted at the suggestion that people need to be vaccinated to eat in a restaurant, or that they should avoid crowds so that the latest variants are not passed around as quickly. Western societies have stooped to offering lottery tickets or even hundred dollar vouchers for those reluctant enough to have avoided the vaccine rollout, hoping to encourage them by carrot, and when that fails, by the stick of fines and restrictions on movement. As well, our fantasy that colonial ways of thinking were relegated to history has been undermined by the fact that the west ensured that they had the vaccine first, and the developing world be damned. Even as people in developing nations are crying out for access to the vaccine, in the west they ensure their people survive by hoarding nearly the entire production of the various vaccine companies.

Efforts to control the virus are to be commended—although some might wonder that such devotion to medical science has been conspicuously absent when malaria was killing six hundred thousand every year in the tropics—but they have also led to a shift in the culture which is starting to become the background normal of our world. Coughing while in public or sneezing are now read as warnings, and that is worse if the ill person is not wearing a mask. Such symptoms of illness were at one time normal public behaviour, just as standing too close to a stranger that might have been seen as peculiar has become rewritten into harassment or assault. While

commended—although some might wonder that such devotion to medical science has been conspicuously absent when malaria was killing six hundred thousand every year in the tropics—but they have also led to a shift in the culture which is starting to become the background normal of our world. Coughing while in public or sneezing are now read as warnings, and that is worse if the ill person is not wearing a mask. Such symptoms of illness were at one time normal public behaviour, just as standing too close to a stranger that might have been seen as peculiar has become rewritten into harassment or assault. While protests have always been relatively common—such as anti-war demonstrations or those worrying at the age-old problem of police forces violence toward minorities—the amount of misplaced and misinformed outrage has reached a kind of tipping point.

protests have always been relatively common—such as anti-war demonstrations or those worrying at the age-old problem of police forces violence toward minorities—the amount of misplaced and misinformed outrage has reached a kind of tipping point.

The ethnicity of those who are fed up with the mandates only works to exacerbate the problem. Covid is a virus which kills indiscriminately. Even if the wealthy stay in their mansions, they will not be able to evade the illness, so the machinery of the pharmaceutical industry responds to such political verities and cranks up to offer a cure. The virus affects older people the most drastically, and wealth is not the universal panacea that it once was. The older wealthier citizen is more likely to be a voter, and is a knowable demographic. The elected politicians know what their older citizens want and they ensure that they will get it. This urgency has mobilized whole countries to smother their industry and trade so that the hospitals will not be overrun, has ensured the mandates dictate that people are to stay at home. This is easy enough for the wealthy,  as they relax at the cottage or in their expansive yards, but for others, primarily the poorer and younger members of society who wonder why they—who tend to survive the illness—need to change society for their elders. The media has also sipped from these contrasting views, as they revel in any news story of a younger person dying of the illness. “It doesn’t just happen to older people,” they trumpet, even while those who are less privileged are suffering.

as they relax at the cottage or in their expansive yards, but for others, primarily the poorer and younger members of society who wonder why they—who tend to survive the illness—need to change society for their elders. The media has also sipped from these contrasting views, as they revel in any news story of a younger person dying of the illness. “It doesn’t just happen to older people,” they trumpet, even while those who are less privileged are suffering.

Many of those who talk about the effect of the virus on society are mostly worried about what they perceive as a loss of freedoms—whatever that means in their terms as they strive to supress the freedoms of others—but there are also other more reasonable voices in the mix. The virus has done much  more than change the way we interact, such as shaking hands with the stranger or wearing a mask when in a public building, the virus is also shaking up society in other ways.

more than change the way we interact, such as shaking hands with the stranger or wearing a mask when in a public building, the virus is also shaking up society in other ways.

There are many societies on the planet, even many more than countries, and their ways of reacting to the pandemic are as various as their members, but a few reactions stand out. The anger over mandates has boiled over often enough now that we have come to see that behaviour as normal. The anti-masker hollering in a shop for someone to call the police while they try to spit on their fellow shoppers, or someone wearing a mask who tries to wrestle a face covering (I could only find a prank video for this) onto the one yelling at them has become the background normal of our world. An undercurrent of anger has rippled through society, just as the racist sensibility of the Nazis affected Germany in the thirties.

As the above example suggests, this frustration is not limited to one “side” or another. It’s a kind of collective insanity. The anti-vaxxers and the anti-maskers are merely a symptom. On the side of the pro-mandate people, there is a whole website dedicated to schadenfreude, where they pillorize the anti-vaxxers by putting up their names and attitudes from posts before revealing they died of Covid death. Meanwhile the anti-vaxxers are becoming an identifiable voting group, and are drawing mercenary politicians into their fold. The mandates can make little purchase on their slippery hides, and the province of Quebec in Canada was driven to limiting access to liquor stores and cannabis shops just to encourage people to take care of their own health.

of Quebec in Canada was driven to limiting access to liquor stores and cannabis shops just to encourage people to take care of their own health.

More than anything else, I think the Covid period represents a great slow down. A kind of interregnum where productivity has dropped to an all-time low. All around us business and government plead Covid when they are called upon to do their job at a level even close to the former alacrity or efficiency. That is the true effect of the virus. My friend used to say that emails warning about viruses which people would forward were the real virus. They fit the definition of a virus, in that they were both annoying time wasters and self-replicating. I learned that a virus cannot be judged only by its appearance under a microscope. A virus has more of an effect that it might seem, and like a computer virus is not limited to merely hardware or software damage, the Covid-19 virus has a ripple effect on all societies.

As if Covid had done its damage to the physical body of the state and was now reaching into the culture, it makes an indelible mark on how we conduct government, draws the battle lines of prejudice and prejudging, and in general wastes the time and energy of an already weakly productive system. The slowdown has also made people revaluate their systems of value. This ranges from questions as diverse as whether churchgoing is a necessary part of the religious enterprise, and whether workers have to be under the gaze of the boss to know their job.

the battle lines of prejudice and prejudging, and in general wastes the time and energy of an already weakly productive system. The slowdown has also made people revaluate their systems of value. This ranges from questions as diverse as whether churchgoing is a necessary part of the religious enterprise, and whether workers have to be under the gaze of the boss to know their job.

There has been some talk in the media about people relearning the lessons of what is important in life, family and free time and time spent in nature, but the other side of that story is one in which the workaholic’s lust for money or power is dulled. The notions in the culture which drove him or  her to long hours finagling money from another’s hand suddenly seem empty when observed with the eyes of the virus. Hoarding money so that it can be enjoyed in old age is beginning to show it flaws, as the nursing homes become victim to grasping corporations taking the money and letting the old people die in their filthy beds. Being old suddenly doesn’t look as attractive, when it means dying alone on a ventilator surrounded by an overworked and stressed hospital support staff. For youth, even if they had ignored reports of climate change, the lesson is clear: enjoy your life now. That makes them much less inclined to follow mandates made by their elders who already control the money and laws of society and now want to control youth as well.

her to long hours finagling money from another’s hand suddenly seem empty when observed with the eyes of the virus. Hoarding money so that it can be enjoyed in old age is beginning to show it flaws, as the nursing homes become victim to grasping corporations taking the money and letting the old people die in their filthy beds. Being old suddenly doesn’t look as attractive, when it means dying alone on a ventilator surrounded by an overworked and stressed hospital support staff. For youth, even if they had ignored reports of climate change, the lesson is clear: enjoy your life now. That makes them much less inclined to follow mandates made by their elders who already control the money and laws of society and now want to control youth as well.

Perhaps because more people are going outside  to enjoy parks and wild areas—since there were few other recreation options—the natural world has also come to take on more importance. Even as the IPCC released their report that we were teetering near a precipice in terms of global greenhouse gas emissions, more people than ever were rushing into the wild that was suddenly under a threat they could imagine or see. Viral videos of clean water such as those which purported to show the return of dolphins to Venice—although they were pre-pandemic and filmed in Sardinia—were only a few of the statements about the earth healing itself from its own virus, human impact on the environment.

to enjoy parks and wild areas—since there were few other recreation options—the natural world has also come to take on more importance. Even as the IPCC released their report that we were teetering near a precipice in terms of global greenhouse gas emissions, more people than ever were rushing into the wild that was suddenly under a threat they could imagine or see. Viral videos of clean water such as those which purported to show the return of dolphins to Venice—although they were pre-pandemic and filmed in Sardinia—were only a few of the statements about the earth healing itself from its own virus, human impact on the environment.

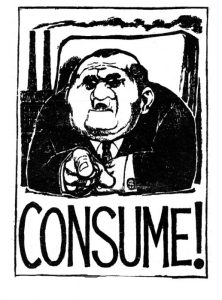

Even as the consumer was turning increasingly to online stores to satisfy their acquisitive urges, the mandates limiting restaurant visits led many to order takeaway through apps like Uber-Eats and Skip-the-Dishes. Even while they watched their screens for evidence that pollution was at an all-time low, their  pitched fast-food containers by the billions. Boxes piled up outside houses as they shopped more and more online, and delivery trucks were some of the only vehicles on the road or passing through international boundaries.

pitched fast-food containers by the billions. Boxes piled up outside houses as they shopped more and more online, and delivery trucks were some of the only vehicles on the road or passing through international boundaries.

Despite the many online orders, shutdowns in many manufacturing centres, especially in China, as well as limits on what shops were open and what they could sell, meant that international trade began to lag. That was exacerbated and  symbolized by the high winds which forced the Ever Given, a twenty thousand container ship that lodged partway through the canal and stopped all trade. A salvage operation finally managed to remove the ship seven days later, but in the meantime international trade had slowed to a crawl and various companies were fighting for compensation. The Ever Given was built and owned in Japan, sailing under contract to a Taiwanese company, registered in Panama, and is the responsibility of a German company. In the confusing world of international trade, no one knew who exactly to blame, and more importantly, who would take responsibility enough to pay for the salvage operation.

symbolized by the high winds which forced the Ever Given, a twenty thousand container ship that lodged partway through the canal and stopped all trade. A salvage operation finally managed to remove the ship seven days later, but in the meantime international trade had slowed to a crawl and various companies were fighting for compensation. The Ever Given was built and owned in Japan, sailing under contract to a Taiwanese company, registered in Panama, and is the responsibility of a German company. In the confusing world of international trade, no one knew who exactly to blame, and more importantly, who would take responsibility enough to pay for the salvage operation.

While they wrangled about such matters, people wanting to buy goods from the sweatshops in the east disappointedly found the store shelves empty, and even Amazon—which seems to hover above regular trade in terms  of delivery just as it does in taxes—had little to offer. The dishwasher and teddy bear was delayed several months, and the local rush on toilet paper—which was nearly a worldwide phenomenon—brought an awareness of such scarcity to the purchaser. The factories themselves had less to ship, even if the routes were secure, for many of the giga-factories of China were closed for fear of virus transmission, and some workers were sealed into their apartments.

of delivery just as it does in taxes—had little to offer. The dishwasher and teddy bear was delayed several months, and the local rush on toilet paper—which was nearly a worldwide phenomenon—brought an awareness of such scarcity to the purchaser. The factories themselves had less to ship, even if the routes were secure, for many of the giga-factories of China were closed for fear of virus transmission, and some workers were sealed into their apartments.

Closer at home conservative governments which had spent their tenure trying to destroy the Canadian health care system suddenly found the same citizens who were rich enough to want a two-tiered system—their most faithful voting bloc—were suddenly afraid their spots in the Intensive Care Units would be taken by the peons they’d worked against. The conservatives, their only response austerity—especially in times of crisis—went ahead with health care cuts, but such moves became increasingly unpopular. Even while they touted unfettered market forces, they begged for taxpayer handouts to protect the rich from themselves, and meanwhile people died of Covid or from the inability to get the surgeries they needed because the health care system, faltering under years of cutbacks, was flagging in the face of the pandemic.

The world wide slowdown, was driven by government workers who lolled around at home without the scrutiny of the boss, by workers realizing that some aspects of their life was more important than money, by workaholics refusing to give their lives away for money which they could no longer spend, and by old people who realized retirement might mean an early death. With the accessibility of some goods restricted, less people could summon up the energy to order them, and with the shops closed for the first time in their lives, people increasingly realized they didn’t need them.

Even while speciality shops cried about lost customers, those which provided for human needs as versus wants—such as grocers and pharmacies—found their business booming.  Humans still had human needs, but they were waking to the great lie of consumer society, that happiness is directly correlated to consumption. Between the growing notion about working from home, and its attendant distractions which lead to less productivity, and a growing environmental sensibility coupled with a revaluation of how to live, productivity has dropped for the first time since the sixteenth century. The exponential growth of humanity has lagged for a moment, and in that chance to catch its breath, millions of people worldwide are wondering anew what they’d been chasing.

Humans still had human needs, but they were waking to the great lie of consumer society, that happiness is directly correlated to consumption. Between the growing notion about working from home, and its attendant distractions which lead to less productivity, and a growing environmental sensibility coupled with a revaluation of how to live, productivity has dropped for the first time since the sixteenth century. The exponential growth of humanity has lagged for a moment, and in that chance to catch its breath, millions of people worldwide are wondering anew what they’d been chasing.