The so-called vanity press has changed little in the public imagination until very recently. Traditionally, paying to have your book published was seen as synonymous with junk novels and sentimental and self-indulgent poetry. The only route to acceptance by the publishing industry and your peers, many would claim, was through a major publisher such as Penguin or Random House (which after the merger is merely Random House). We often forget that the so-called traditional publishing houses are, of course, a new phenomenon and have a limited life cycle like anything else.

Many years ago writers didn’t get paid for their work and that was seldom the focus of why they wrote. They wrote for the edification of their tiny public in those times of general illiteracy, and were satisfied if they made a contribution to their community. For example, Jonathan Swift, of Gulliver’s Travels fame, wasn’t typically paid for his work but rather published in order to be read. Similarly, Henry David Thoreau joked that “I now have a library of nearly nine hundred volumes, over seven hundred of which I wrote myself.” Self-publishing was relatively common way for writers, especially those with an entrepreneurial spirit, to build their audience.

This is not just an ancient phenomenon limited to those writers that many agree are classic authors but few have read. Dozens of relatively recent writers have been known to self-publish as well, such as Ezra Pound, Margaret Atwood, Ernest Hemingway, and Stephen King.

Two very recent self-published authors have done more to change the face of publishing and inspire those who wish to write than thousands before them, however. As well, perhaps inadvertently, they have done much to bring the edifice that is the publishing industry to heel.

Hugh Howey is the science fiction author responsible for the Silo books, a post-apocalyptic series which examines the survivors of  a nanotechnology disaster. His well-written books have sold in the millions and, because they were self-published primarily on the Amazon Kindle platform, have done much to bring the potential of that delivery method to authors and readers. Howey is a committed advocate for self-publishing and the reader-centred experience and maintains a strong web presence even though he has used his proceeds to sail the world in his new yacht.

a nanotechnology disaster. His well-written books have sold in the millions and, because they were self-published primarily on the Amazon Kindle platform, have done much to bring the potential of that delivery method to authors and readers. Howey is a committed advocate for self-publishing and the reader-centred experience and maintains a strong web presence even though he has used his proceeds to sail the world in his new yacht.

What is particularly inspiring about Howey’s success is how matter-of-fact he is about his achievement. He gives thanks to his readership and praises the Kindle platform, and acknowledges that he worked hard to perfect his craft. Also, Howey makes his success sound possible for others, and many are those who wish to follow his financial trail, although they may be less interested in the hard work of writing.

He is not the only  success story; James Redfield sold 100,000 copies of his first book, The Celestine Prophecy, out of the trunk of his car before being offered a book deal by Warner Books. Subsequently, the Prophesy spent years on the New York Times bestseller list. Likewise, Lisa Genova self-published Still Alice through iUniverse

success story; James Redfield sold 100,000 copies of his first book, The Celestine Prophecy, out of the trunk of his car before being offered a book deal by Warner Books. Subsequently, the Prophesy spent years on the New York Times bestseller list. Likewise, Lisa Genova self-published Still Alice through iUniverse  (2007) before it was bought by Simon & Schuster once it had proved itself in the market. Success stories about well-written books are only part of the publishing story, however.

(2007) before it was bought by Simon & Schuster once it had proved itself in the market. Success stories about well-written books are only part of the publishing story, however.

Another part of the narrative is the market research that is already done by word of mouth and social media  so that books like Beth Reekles’ YA novel, The Kissing Booth, has millions of downloads despite the fact that she was a 17-year-old self-published high school student. Her book was snapped up by Random House, whose million-dollar three-book deal likely has inspired many other high school students to try their hand at the keyboard.

so that books like Beth Reekles’ YA novel, The Kissing Booth, has millions of downloads despite the fact that she was a 17-year-old self-published high school student. Her book was snapped up by Random House, whose million-dollar three-book deal likely has inspired many other high school students to try their hand at the keyboard.

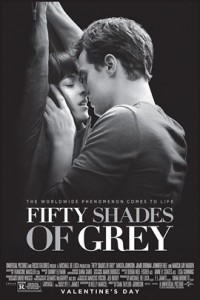

E. L. James’, or more accurately, Erika Leonard’s Fifty Shades of Grey is a success story very different in kind. Ms. Leonard began her publishing odyssey by posting fan fiction on Twilight fan  sites, and was soon so popular that she took the advice of her new community and brought out an eBook of her stories. An immediate and runaway success, her eBook and subsequent print copy have sold over a hundred million copies. Some derisively label the book, and later the series, as housewife porn, but few deny that Ms. Leonard has struck a nerve and that nerve has produced gold.

sites, and was soon so popular that she took the advice of her new community and brought out an eBook of her stories. An immediate and runaway success, her eBook and subsequent print copy have sold over a hundred million copies. Some derisively label the book, and later the series, as housewife porn, but few deny that Ms. Leonard has struck a nerve and that nerve has produced gold.

What is particularly inspiring about Leonard’s success is how poorly written her book is. The story is trite, unrealistic and, according to Emma Green from The Atlantic, dangerously out of step with modern notions of consensual if alternative sex. For my own part, I am more interested in the books’ extreme popularity. They are so popular, in fact, that they have brought the major publisher Random House begging. Likely this is due to the fact that the books have already developed an audience and therefore cost nothing to advertise. I’m not sure what happened over at Random House, but perhaps that news made the marketing department thoughtlessly manic, but whatever the reasons, when Random bought the rights to her text they published it virtually unchanged.

For the writer, that is more than inspiring. The largest publishers in the world who claimed that self-publishing is the last resort of the desperate author whose terribly written and unedited trash cannot sell otherwise, have taken on what basically is unedited trash as long as there is money in it. We’re not surprised that they are a money-making enterprise, but we were often fooled by their statements about the quality of their output. We are no longer confused. As American author Ken Poyner said very damningly and succinctly, many self-published eBooks look like they “were written with rocks, by rocks, for rocks, on rocks,” and now one of those dull stones has exposed the industry for what it is. If the major publishing houses so obviously don’t care about excellence, then the last holdout of their power, the myth that they are arbiters of quality and gatekeepers to the sacred library, implodes.

Random House may not be worried about their reputation after publishing a book which makes so much money, but for those of us who pay attention to our craft, who labour to produce art, it is rather freeing to think that the last barrier keeping someone from sending a book into the world on Amazon is gone. Hugh Howey told us we could do it, and Erika Leonard’s success shows us that the major publishing houses’ claims of excellence and literary merit was a smoke screen. We can thank both of them for opening up the market to the writer who wishes to send their work directly to their readers and not worry about the opinions of a middleman industry that has finally exposed its greedy and soiled hand.