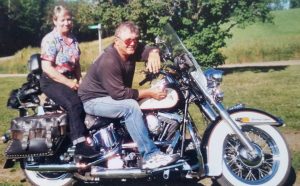

When Cousin Nick wanted to make a documentary about me he wasn’t that impressed when he interviewed my friend Mento  Wong. Mento was a biker friend of mine who’d spent his life railing against conformity and worked as an operator supervisor in a pulp mill. In both those ways, he was the antithesis of Cousin Nick. Not only was Mento thoroughly a member of the working classes, he also never subscribed to a rule merely because someone told him he should. He was the exact opposite, in fact, and felt that our actions needed to be rationalized logically. One time he tired of the neighbours telling each other when to mow their lawns so he mowed half his lawn, shut down the mower in the middle of the lawn and left it there for three weeks. Nick said, after the interview, that he didn’t think there would be much footage that was useful, but I suspected, even from the little that I had heard, that Mento would do splendidly.

Wong. Mento was a biker friend of mine who’d spent his life railing against conformity and worked as an operator supervisor in a pulp mill. In both those ways, he was the antithesis of Cousin Nick. Not only was Mento thoroughly a member of the working classes, he also never subscribed to a rule merely because someone told him he should. He was the exact opposite, in fact, and felt that our actions needed to be rationalized logically. One time he tired of the neighbours telling each other when to mow their lawns so he mowed half his lawn, shut down the mower in the middle of the lawn and left it there for three weeks. Nick said, after the interview, that he didn’t think there would be much footage that was useful, but I suspected, even from the little that I had heard, that Mento would do splendidly.

For instance, when Mento spoke about the nascent environmental movement, his evocative sentences still ring true today. He said, “You should know, today, the more we go, the worst everything gets. Like the forests, and the water, you know. They’re trying to go back to green now,  but they’re kind of waiting for the wrong time. They should have done it years ago.”

but they’re kind of waiting for the wrong time. They should have done it years ago.”

The most compelling portions of this quote are likely those Cousin Nick found the most troublesome. Mento didn’t have an extensive formal education, and everything he knew he had largely taught himself or learned from others in a more informal setting. The grammatical problems with the adjectives in “the worst everything gets” would rankle Cousin Nick, but provides the jarring word play which makes Mento’s utterance even more accurate and powerful. The comparative adjective of “worse” would not be as effective in his sentence, and on some level, Mento sensed that. The “everything” that is getting worse is not just bad when compared to something else, it is much worse than that. Mento knew for his sentence to be the most  damning, he needed the superlative adjective. Everything is not just getting worse than some other thing, it is getting “worst,” which is much more compelling than the grammatically correct option. The list of bad things is not just two—as “worse” implies—with the environment slightly lower, the list is made of numerous elements, and the environment is at the bottom. Mento’s instincts are similarly accurate when he begins to make a list of the environmental disasters, starting with the “forests” and the “water,” but he

damning, he needed the superlative adjective. Everything is not just getting worse than some other thing, it is getting “worst,” which is much more compelling than the grammatically correct option. The list of bad things is not just two—as “worse” implies—with the environment slightly lower, the list is made of numerous elements, and the environment is at the bottom. Mento’s instincts are similarly accurate when he begins to make a list of the environmental disasters, starting with the “forests” and the “water,” but he  then ends it abruptly. He knows his audience realizes exactly what he is talking about, and the list is so exhaustive that the “everything” from the previous sentence barely can encapsulate it.

then ends it abruptly. He knows his audience realizes exactly what he is talking about, and the list is so exhaustive that the “everything” from the previous sentence barely can encapsulate it.

When Cynthia Bissell, my nursing friend and Cousin Nick’s aunt, is interviewed she makes a similar statement about my stance on the environment, and because she is just as honest as Mento, she is quite upfront about our collective, albeit unsaid, environmental realization: “An issue that is big for Bear, that really bothers him, is the fact that the planet is overpopulated. There’s way too many humans and humans just wreck everything, and I don’t think that’s a secret I think we all realize that.”

Such environmental sentiments have been echoing in our society for a number of years now, but where Mento’s statement really shines is in the mixture of tenses used in his last sentences: “They’re trying to go back to green now, but they’re kind of waiting for the  wrong time. They should have done it years ago.” Who they are who are “trying to go back to green” is debatable, but presumably Mento was talking about society in general. The “trying,” however, implies the process is ongoing, and the “waiting for the wrong time” tells us that they are not trying at this moment—both overturning what he said earlier and casting doubt about their seriousness. The “wrong time” the environmentalists, or anyone who wants to go back to green is “waiting for” is also doubly problematic. Over and above the comic undercutting of “waiting” for “time,” Mento says that the time will be wrong even when they find it.

wrong time. They should have done it years ago.” Who they are who are “trying to go back to green” is debatable, but presumably Mento was talking about society in general. The “trying,” however, implies the process is ongoing, and the “waiting for the wrong time” tells us that they are not trying at this moment—both overturning what he said earlier and casting doubt about their seriousness. The “wrong time” the environmentalists, or anyone who wants to go back to green is “waiting for” is also doubly problematic. Over and above the comic undercutting of “waiting” for “time,” Mento says that the time will be wrong even when they find it.

The “waiting for the wrong time” also suggests that they are waiting for someone else to fix the problem, even if their commitment to “waiting” wasn’t already undermined by the “kind of.” They are not waiting on a change in their circumstances, or even the environment to improve on its own, Mento warns, they are merely waiting for a certain “time.” Mento makes it clear what he thinks about this time they are waiting for; it’s “wrong,” as far as he is concerned. The action they  are “trying” to do, is to “go back to green.” Through this historical placement, Mento claims that there was a greener time to live, a moment in the past which was more environmentally sound. That suggests that we have the skills needed to “go back to green,” and goes even further to ridicule the half-hearted “trying” of the first part of the sentence.

are “trying” to do, is to “go back to green.” Through this historical placement, Mento claims that there was a greener time to live, a moment in the past which was more environmentally sound. That suggests that we have the skills needed to “go back to green,” and goes even further to ridicule the half-hearted “trying” of the first part of the sentence.

The last part of his utterance is equally interesting, for it suggests that if “they” were going to return to some earlier golden age of environmental consciousness, that should have been  done “years ago.” He is not suggesting that it is too late, but rather all of the “trying” and “waiting” has done nothing. We had the skills at our command—we can think of the parsimonious behaviour of our depression-era grandparents—and we never bothered to return to those ways of living before. As the time grows later and later, Mento suggests, this will only become more difficult.

done “years ago.” He is not suggesting that it is too late, but rather all of the “trying” and “waiting” has done nothing. We had the skills at our command—we can think of the parsimonious behaviour of our depression-era grandparents—and we never bothered to return to those ways of living before. As the time grows later and later, Mento suggests, this will only become more difficult.

Mento Wong died a few years after the documentary was made (You can view Searching for Bear – a Portrait of a Life on YouTube), but his message about a culture dragging its collective reluctant feet, that the skills we need are ones we possessed historically, and that “going back to green” is urgent, is still as relevant as when Mento said it.