The story of both Parks and Helen Keller have been so heavily overwritten by the public imagination that they are almost invisible in a narrative ostensibly about them. This line drawing of their lives looms much larger than the more complex painting that would be a more representative telling, and the photograph that would contain both their flaws and triumphs is smudged by hands more dirty than eager.

Perhaps because they were both strong women, who the public would like to fantasize stood alone against the world, they are seldom granted the same human subtlety and complexity of other public figures. Both women have made a mark on history, but the dulling of that mark by the received story of their lives and accomplishments means that for many it is a background stain instead of a vivid demarcation of rights and strength. For many today, the dominant story represents all they may ever know, and just as information is mishandled by the controllers of the archive, the reasons for those exclusions are equally manifold and possibly malign.

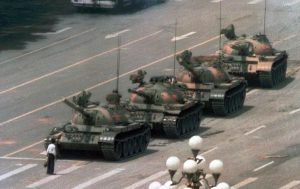

For our purposes, it is worthwhile noting that their contribution has been minimized, that their agency was questioned, and that much of their strength was diffused into stories which made them accidental or inadvertent heroes. This is not an  accident. For the cross between the Tiananmen Square and the Horatio Alger story to work, for the two women to go against the tank of social censure and law and succeed, they have to act alone and not possess secret and especially political motivations.

accident. For the cross between the Tiananmen Square and the Horatio Alger story to work, for the two women to go against the tank of social censure and law and succeed, they have to act alone and not possess secret and especially political motivations.

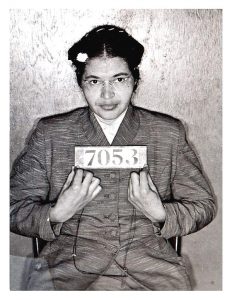

The dominant narrative about Parks was that she was a tired commuter on a bus going home after a long day at work. The white people standing that meant the bus driver demanded her seat was the final straw, we are told, and

Rosa Parks seated toward the front of the bus, Montgomery, Alabama, 1956. (Photo by Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

she had had enough. Standing up to him, she became—in the story at least—the first American black person to demand equal treatment, and her arrival in the Supreme Court to overturn Alabama’s Jim Crow laws was merely the natural result of that inadvertent action. The salient features of Rosa’s poignant stand against injustice are a lone black woman standing against a white man, the idea that the injustices had worn on her until she was angry enough to do something, and the element of chance the dominant narrative makes essential to the story.

The accepted Helen Keller story is much the same. Being both deaf and blind, she is idolized and constrained by more than just the community of people with disabilities. Because she was also an attractive woman,  and had no behavioral problems, she became a poster child every bit as much as Parks. In the dominant narrative she is a sweet innocent, for the notion of disability at that time, and perhaps even now, could not include a temper, a will of her own, or even worse, sexuality. Instead, Keller was demure, patient, long-suffering and yet working at overcoming her issues, virginal vessel of the lord.

and had no behavioral problems, she became a poster child every bit as much as Parks. In the dominant narrative she is a sweet innocent, for the notion of disability at that time, and perhaps even now, could not include a temper, a will of her own, or even worse, sexuality. Instead, Keller was demure, patient, long-suffering and yet working at overcoming her issues, virginal vessel of the lord.

Like Rosa Parks, Helen Keller became more symbol than a person in her own right, and the dominant narrative reflects that. In the accepted telling, Parks becomes the brave black housewife who strove against an unjust government on a whim and Keller the resolute soul struggling against the darkness of her existence to try to be as normal as possible. An advocate of the deaf learning to speak with audio signifiers, Alexander Graham Bell provided her with encouragement to speak even while she became the image for deaf centres where children were housed. Bell is not as popular with the deaf community today, for the school’s policy of tying children’s hands behind their back so they couldn’t sign is now viewed as barbaric, and the implications, that only audio speech was permissible, reactionary. A strong proponent of radical inclusion, Bell believed that the deaf should be fully integrated into society, although that might mean they would be forever relegated to the margins.

Although he was a supporter, Keller was also useful to Bell in his own drive to ignore disability, and he was not above perpetuating an image that suited the story he wanted to tell about Keller’s accomplishments. That version of Keller becomes the dominant one that school children are taught. This version is recorded by the Dunn County News on January 22, 1916 in Menomonie, western Wisconsin. Keller gave a lecture at the Mabel Tainter Memorial Building about her struggles and the writer in this small weekly, at least, heard what they wanted to hear. The notion of the triple affliction as well as the infantilising language used to describe this thirty-six-year-old woman is instructive:

A message of optimism, of hope, of good cheer, and of loving service was brought to Menomonie Saturday — a message that will linger long with those fortunate enough to have received it. This message came with the visit of Helen Keller and her teacher, Mrs. John Macy, and both had a hand in imparting it Saturday evening to a splendid audience that filled The Memorial. The wonderful girl who has so brilliantly triumphed over the triple afflictions of blindness, dumbness and deafness, gave a talk with her own lips on “Happiness,” and it will be remembered always as a piece of inspired teaching by those who heard it.

In fact, Keller was as much a girl as she was a demure and passive woman living with “Afflictions.” That Keller was both a woman and an activist dismayed her contemporaries. A woman with disabilities was not permitted sexual desires, and both her family and her teacher ensured her love affair went no further than reading signed onto her hand. Her attempted elopement with Peter Fagan, a reporter for the Boston Herald, shocked her contemporaries, and such was the value of her image to the community that she was not allowed the normalcy of a lover or a husband.

Keller was permitted to develop her political life more than her private life. She became a world-famous speaker and author. She was an advocate for people with disabilities, a suffragette, a pacifist, an opponent of Woodrow Wilson, a radical socialist and a supporter of birth control. She was one of the founding members of the Helen Keller International organization in 1915, which devoted itself to research in vision, health and nutrition. She was also one of the founding members of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920. A member of the Socialist Party, she supported the Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs in his campaigns for presidency and joined the Industrial Workers of the World because of her concern about blindness and other disabilities that broadened into an investigation into worker’s rights:

“Then I was appointed on a commission to investigate the conditions among the blind. For the first time I, who had thought blindness a misfortune beyond human control, found that too much of it was traceable to wrong industrial conditions, often caused by the selfishness and greed of employers. And the social evil contributed its share. I found that poverty drove women to the life of shame that ended in blindness.

“Then I read H.G. Wells’ Old Worlds for New, summaries of Karl Marx’s philosophy and his manifestoes. It seemed as if I had been asleep and waked to a new world–a world so different from the beautiful world I had lived in.

“For a time I was depressed but little by little my confidence came back and I realized that the wonder is not that conditions are so bad, but that humanity has advanced so far in spite of them. And now I am in the fight to change things. I may be a dreamer, but dreamers are necessary to make facts!” (Interview with Keller by Barbara Bindley New York Tribune, January 16, 1916)

During that same interview, Barbara Bindley asks Keller “What are you committed to–education or revolution?” and Keller answered “Revolution. We can’t have education without revolution. We have tried peace education for 1,900 years and it has failed. Let us try revolution and see what it will do now” (Interview with Keller by Barbara Bindley New York Tribune, January 16, 1916). The shy virgin that the dominant narrative has constructed is not as easy to locate when we listen to Keller’s own words or peruse her history.

Being at odds with the dominant narrative comes at a cost, however, for even while Keller was disallowed her maturity or sexuality, the disability that was a source of her strength in the legend of Helen Keller was used against her when she spoke of Socialist beliefs. The editor of the Brooklyn Eagle wrote that her “mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development.” Keller’s response to the editor are more cutting than demure:

But now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error. I must have shrunk in intelligence during the years since I met him. … Oh, ridiculous Brooklyn Eagle! Socially blind and deaf, it defends an intolerable system, a system that is the cause of much of the physical blindness and deafness which we are trying to prevent. (Keller, Helen. “How I Became a Socialist”. The New York Call. (November 3, 1912) Helen Keller Reference Archive.)

Keller was considered to be too radical at the beginning of the 20th century, and as a consequence, her political views have been forgotten or ignored as the narrative of her withdrawing self gained even more traction in the public mind.

Parks’  image is equally mistaken and glowing, although perhaps not quite as condescending. In her autobiography, My Story she complains about the way her political gesture was positioned:

image is equally mistaken and glowing, although perhaps not quite as condescending. In her autobiography, My Story she complains about the way her political gesture was positioned:

People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.

As an explanation for her choice to stand—or at least sit—for equality, she talks candidly about her decision as a demand for her civil rights:

I did not want to be mistreated, I did not want to be deprived of a seat that I had paid for. It was just time… there was opportunity for me to take a stand to express the way I felt about being treated in that manner. I had not planned to get arrested. I had plenty to do without having to  end up in jail. But when I had to face that decision, I didn’t hesitate to do so because I felt that we had endured that too long. The more we gave in, the more we complied with that kind of treatment, the more oppressive it became.

end up in jail. But when I had to face that decision, I didn’t hesitate to do so because I felt that we had endured that too long. The more we gave in, the more we complied with that kind of treatment, the more oppressive it became.

Meg McAleer, an archives specialist working on the Parks papers, speaks to both the myth of Parks and the reality of the activist and gifted political writer:

You know, we think of her as the quiet seamstress, and her writing just absolutely blew me away — the strength of it, the power of it, the courage of it. I mean, she’s writing things down about the way things are in the South in ways that could get her killed, and she’s unflinching in how she does it. (In conversation with NPR’s Audie Cornish about the documents.)

Even as a child, Rosa Parks was sensitive to inequality in the racist system of Alabama’s enactment of the Jim Crow laws when she walked to school and the white children were bused: “I’d see the bus pass every day… But to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world” (“The Story Behind the Bus.” Rosa Parks Bus. The Henry Ford). When she pursued her education and finished high school, less than seven percent of black Americans had a high school diploma. In 1943, she joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, and was, likely because she was the only woman, elected secretary. She later said, “I was the only woman there, and they needed a secretary, and I was too timid to say no.”

In 1944, in her capacity as secretary, she investigated the gang-rape of Recy Taylor, a black woman from Abbeville, Alabama. Parks and other civil rights activists organized the “Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor”, launching what the Chicago Defender called “the strongest campaign for equal justice to be seen in a decade.” She attended meetings of the Communist Party and both Parks and her husband were members of the Voters’ League.

On December 1st, 1955, she made her famous declaration against systemic racism by refusing to give up her seat when the driver moved the sign that indicated the black section in order to appease white customers. Her action, and that of other activists, polarized the community and plans for the Montgomery Bus Boycott were announced three days later at black churches in the area. The community determined to continue the boycott until they were treated with the level of courtesy they expected, until black drivers were hired, and until seating in the middle of the bus was handled on a first-come basis. Parks was found guilty of charges of disorderly conduct and violating a local ordinance and fined ten dollars, plus four dollars in court costs. On her appeal, Parks formally challenged the conviction on the grounds of the legality of racial segregation.

The boycott was a rousing success with nearly the entire community participating. Some rode in carpools, while others traveled in black-operated cabs that charged the same fare as the bus. Some even walked, some of them many miles. As if to show that even though she was fighting segregation on the bus system and yet hadn’t won the fight, when she was called upon to speak at a church rally, the crowd was told by male organizers that she had already had her say by her actions.

Although the boycott lasted just over a year, Parks’ court case was only slowly making its way through the labyrinthine appeal structure of the Alabama courts on its way to a Federal appeal. Before she had her day in federal court, the city of Montgomery repealed the segregation law on public buses in order to conform to the US Supreme Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that it was unconstitutional.

Parks played an important part in raising international awareness of the plight of African Americans and the civil rights movement. After her arrest, she became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement but lost her job at the department store because of economic sanctions. She lived with constant death threats, even as she continued to participate in activism during the mid-1960s. She marched in support of the Selma-to-Montgomery Marches, the Freedom Now Party, and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. She was active in the movement for better housing in Detroit and had strong opinions on the racist policies that had gutted black communities in favour of development and in support of protestors. She worked with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Republic of New Afrika in raising awareness of police abuse during the conflict and served on a “people’s tribunal” in August 30, of 1967 that investigated the killing of protestors by police. She was active in the black power movement, and supported and visited the Black Panther school in Oakland.

In her later years, during the 80s, Parks returned to civil rights and educational organizations. She co-founded the Rosa L. Parks Scholarship Foundation for college-bound high school seniors, and co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development. That organization ran the “Pathways to Freedom” bus tours which introduced young people to important civil rights and Underground Railroad sites throughout the country. Parks also served on the Board of Advocates of Planned Parenthood.

History remembers both of these dedicated activists, but the way that it remembers them is not dissimilar to how Keller’s family held her back from her lover and Parks was kept from speaking in the church meeting. Following the spirit of that implicit sexism and ableism, the dominant narrative modifies their received image because it is impossible to efface them completely. Instead of a story that tells of a lifelong dedication to activism, Rosa Parks becomes a disgruntled commuter who got lucky and changed a law, and  Helen Keller becomes a sad misanthrope looking toward a window she cannot peer through. The almost cartoon quality that is the treatment of both their stories cheapens both the story and the women who are now subject to history’s evaluation and evocation of their accomplishments.

Helen Keller becomes a sad misanthrope looking toward a window she cannot peer through. The almost cartoon quality that is the treatment of both their stories cheapens both the story and the women who are now subject to history’s evaluation and evocation of their accomplishments.

As I’ve alluded to above, this gradually devolving story is not accidental. At a time when the civil rights movement was calling upon the feminist movement to wait for the men to fix society, when notions of disability were still tainted with the holy fool of medieval legend and a woman in a progressive organization could expect to be a secretary, Helen Keller and Rosa Parks were doubly confounded by their society. Even while they worked tirelessly against oppression, the story of who they were and their motivations were subject to the same power struggles.

In the end, the story of two women who succeeded in eking out an existence against great odds, standing before the tank that is our cultural ignorance, who were used as figureheads but never asked their opinion, won out against the more factual account. All is not lost, however, for digging through the extant archive the modern historiography can find tantalizing hints that indicate that these two fierce advocates and activists still hover somewhere behind the story that is repeated in schools and chuckled over in the boardrooms.