In a short but provocative exchange between Doctor Frankenstein and Igor in Mel Brooks’ 1974 parody Young Frankenstein, Igor makes a profound statement about our lack of self knowledge. The doctor asks him if he wishes to consider a surgical alternative to the hump on his back, but Igor, with a gleam in his eye that acknowledges that the doctor will not continue the questioning, asks what hump?

Every time I have thought about this scene, with Igor’s oblivious obstinacy, his utter unwillingness to admit the truth about his physical deformity, I was always reminded of that aspect of the human condition which makes us unable, or unwilling to admit our foibles and concerns.

Every time I have thought about this scene, with Igor’s oblivious obstinacy, his utter unwillingness to admit the truth about his physical deformity, I was always reminded of that aspect of the human condition which makes us unable, or unwilling to admit our foibles and concerns.

Although we point to our ability to recognize ourselves in the mirror with great glee, as if that accomplishment incontrovertibly sets us apart from the other animals, we are most exercised when we try to probe our own motivations and concerns. We often claim that we understand what we want, can explain what we do, and are not mystified when we stymie our own aims, but in fact stepping aside from the only perspective our life offers us is more difficult than we pretend.

One of the most pernicious aspects of mental illness, for example, is the inability to recognize it, even if the person who suffers from mental illness can acknowledge their plight. My friend told me about her friend who refused medication because “it messed with his mind.” She expressed her dismay by telling me, “He needs his mind messed with.” Even if the person with mental illness can admit their situation, they somehow avoid using that most salient information to evaluate their own behaviour and ideation.

There are a few techniques we can use  to force us to acknowledge another point of view. When we were young someone probably told us that we needed to walk in another’s shoes, and that advice holds even though we are theoretically more mature when we are older.

to force us to acknowledge another point of view. When we were young someone probably told us that we needed to walk in another’s shoes, and that advice holds even though we are theoretically more mature when we are older.

We should evaluate all of our behaviour from this outside perspective. As we examine each of our choices and statements as if another were to do the same, we can get that sense of dislocation that we need to aim for. If you have ever watched a beloved movie with a friend who didn’t care for it, you have already had an inkling of the power of perspective. Because humans are social animals we automatically place ourselves in the subject position of our peers,  even if that position conflicts with our opinion or values. When our friend tells us the narrative choices in our favourite film are weak, we can either argue with them and thus learn nothing from this valuable moment, or we can look with fresh eyes at what has been hidden by our enjoyment. If the film is worthy of our accolades then it can endure some criticism. If our enjoyment is based in fond unshared memories, or other emotional tags, then we can learn to evaluate our own likes more clearly.

even if that position conflicts with our opinion or values. When our friend tells us the narrative choices in our favourite film are weak, we can either argue with them and thus learn nothing from this valuable moment, or we can look with fresh eyes at what has been hidden by our enjoyment. If the film is worthy of our accolades then it can endure some criticism. If our enjoyment is based in fond unshared memories, or other emotional tags, then we can learn to evaluate our own likes more clearly.

In our life, we need to learn to evoke this same dislocating critical eye. We can do that by imagining another were making the same statements, or imagine that our audience were another person whose opinion we possibly value more. If the statement is true, then we should be able to make it before our best friend, our parents, and our lover. If the action we  have just preformed, such as a petty crime can be explained in a way that salves our conscience, then how well does it fare against the evaluative process of the court.

have just preformed, such as a petty crime can be explained in a way that salves our conscience, then how well does it fare against the evaluative process of the court.

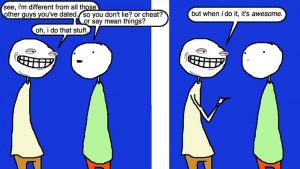

I have a friend who evades all of this responsibility for his actions by trying to ensure that no one knows anything about him. He has a deep-seated social anxiety, he tells me, and therefore worries that no one will like him if they knew his real self that he keeps hidden. His answer to this is not to make sure both his public self and hidden self are  worthy of approbation, but rather he merely keeps his depredations secret. He has no fear of engaging in quite reprehensible actions, as long as no one finds out. His fear that people will not like him once they get to know the real him, is quite valid. He engages in quite unsettling behaviour morally, and yet that does not trouble him in the least since no one is privy to his actions.

worthy of approbation, but rather he merely keeps his depredations secret. He has no fear of engaging in quite reprehensible actions, as long as no one finds out. His fear that people will not like him once they get to know the real him, is quite valid. He engages in quite unsettling behaviour morally, and yet that does not trouble him in the least since no one is privy to his actions.

When he is found out, he suffers all of the agony of the socially fearful, but when I look at his situation I merely ask why he doesn’t change his behaviour. We all have secrets that we’d rather people not know, shabby furtive things we have done or thought, but social anxiety is unimaginably worse when your secrets point out that you make little effort to act in a moral fashion.

When a friend’s child was in the bathroom next to the kitchen when they were discussing his lack of attention to his schoolwork he was listening attentively. One phrase they used excited him enough to burst from the bathroom with demands and expostulations. One parent said to another, “Maybe it’s time we got Ritalin.” If you have never heard the name of the drug, and you were a child listening through a bathroom door, you might hear something quite different. The child heard, “Maybe it’s time we got rid-of-him.”

When I heard this story my first reaction was to laugh with the parents as they described how they placated his fears, but upon reflection I realized an odd aspect of the child’s behaviour. He burst from the bathroom demanding that they don’t get rid of him. For me, that defined a way of thinking. He did not quietly listen for more information that he might use to ensure they kept him. He didn’t reconsider how lazy he had been with his schoolwork or even ask what they meant. Instead, he was sure of what he had heard and he leapt straight to demands. He never considered that his behaviour was the  problem they were discussing and therefore needed to be modified. He was fine, in his own mind. Instead he wanted to modify their behaviour. “What hump?” he came out yelling.

problem they were discussing and therefore needed to be modified. He was fine, in his own mind. Instead he wanted to modify their behaviour. “What hump?” he came out yelling.

Another friend was treating me to a four day diatribe about her ex-boyfriends, complete will all of the shades of meaning that she attached to each of their interactions, when I began to notice a pattern. In every story, she would mention  how angry she was, or how mad that made her. We were walking when I made this observation, and perhaps I hoped that she would therefore rethink her interactions with others. Instead, she merely replied flippantly, “Didn’t you know I have anger issues?”

how angry she was, or how mad that made her. We were walking when I made this observation, and perhaps I hoped that she would therefore rethink her interactions with others. Instead, she merely replied flippantly, “Didn’t you know I have anger issues?”

The gay tone of her voice belied her statement, although I had ample evidence to indicate that her anger issues were rampant, but I wondered why—if she understood that to be a flaw in herself—she did not apply that to her own life. Shouldn’t those anger issues inform her interactions with her boyfriends and help to explain why simple conversations might go awry? Instead, she was both blind to her own hump and was able to use it as a ready excuse, all the while keeping her anger intact and justified.

If we have a hump it behooves us to recognize it. We do not need to belabour it in public, we need not parade it before others, but we should recognize that having a hump will affect our ability to buy a fitted suit off the rack. And even in approaching a tailor, we might want to realize that it is our hump that drives us to the professionals. That is not the tailor’s fault, or that of anyone else.

Another technique we can employ is to examine our motivations in the same way we would another. The reactions of our peers are a clue. If they are taken aback by something we have said, we should re-examine why we are saying it. Are we angry when making the statement, or influenced by alcohol, drugs, hunger, or exhaustion? Like a baby who has not had enough sleep, we can get cranky without knowing what it means or whose fault it is. My good friend was quite annoyed recently and at one point she said, “Why are you being so irritating today?” I suspected that the answer—that she was tired and had a bad day—would have little currency until she was more rested, but I was surprised that it didn’t occur to her.

It is not easy to carry a hump, but at least if our issues are in the open we can point to them as we strive to go beyond their limitations. When Igor asks the question, Doctor Frankenstein merely looks to one side and then abruptly changes the topic. Likewise, with our secret hump, we are left with pretending it does not exist, lying about its effect, or going through our life oblivious and unconcerned, while around us others bend and sway and modify themselves so as not to discommode a hump we refuse to specify.