Conversations on public transit are less frequent with each passing year. Although print media in the form of books and newspapers have always protected the less socialized from interaction, that has been exacerbated by the use of smart phones.  Normally any conversation that happens now is between people who are already known to each other and came aboard the bus together, or a one-sided interaction with someone who is slightly off and doesn’t realize that the code of Canadian behaviour prohibits interaction with strangers.

Normally any conversation that happens now is between people who are already known to each other and came aboard the bus together, or a one-sided interaction with someone who is slightly off and doesn’t realize that the code of Canadian behaviour prohibits interaction with strangers.

I was that talkative person a few months ago, when my express bus was inching along in traffic due to the construction on campus and the university workers salivating for home at the same time.  I was standing at the front of my crowded bus as it swung us forward and back and moved only a metre at a time. I looked at the people near me and said emphatically, “Thank god I got the express.” Their reaction was typical. Even though they weren’t occupied with a phone—for they needed their hands free to hold on—they merely gave a half-smile and looked away. Talking on the bus is tantamount to a diagnosis, they seemed to suggest, and they wanted no part in the straitjacket I was sure to soon require.

I was standing at the front of my crowded bus as it swung us forward and back and moved only a metre at a time. I looked at the people near me and said emphatically, “Thank god I got the express.” Their reaction was typical. Even though they weren’t occupied with a phone—for they needed their hands free to hold on—they merely gave a half-smile and looked away. Talking on the bus is tantamount to a diagnosis, they seemed to suggest, and they wanted no part in the straitjacket I was sure to soon require.

An exception to that was another trip around the same time, when I went aboard the bus with one of my international students and we were talking about how the unsocialized Canadians cannot seem to talk to others. We were loud enough in our expostulations, but no one near us responded. Instead, another man standing behind us piped up  and exclaimed that he’d noticed the same thing. We brought him into our talk, and before long my friend left the bus and I was avidly chatting with my new friend. I asked him why he refused to follow the rule to ignore all others, and he explained that it might be the result of having been adopted from overseas. Although he was young when he came to Canada, he thought that might have made him stand apart from the bizarre social norms of his new country.

and exclaimed that he’d noticed the same thing. We brought him into our talk, and before long my friend left the bus and I was avidly chatting with my new friend. I asked him why he refused to follow the rule to ignore all others, and he explained that it might be the result of having been adopted from overseas. Although he was young when he came to Canada, he thought that might have made him stand apart from the bizarre social norms of his new country.

On my bus last week I was able to witness an exception to the golden silence and frigid social norms that govern most interactions with strangers on western public transit. I was standing near the driver and directly in front of me was a woman who was messaging back and forth. Because I am naturally nosey, I looked over her shoulder and I was surprised to see that she was most interested in messages she’d sent.  Although I couldn’t read the small printing without my reading glasses—and I wasn’t quite curious enough to make my intentions obvious by taking them out of my bag—I could tell that she was scrolling slowly through long sequences of messages she’d sent to someone else.

Although I couldn’t read the small printing without my reading glasses—and I wasn’t quite curious enough to make my intentions obvious by taking them out of my bag—I could tell that she was scrolling slowly through long sequences of messages she’d sent to someone else.

There was another couple standing beside her, and the woman leaned on the man, which made me think about how much more difficult it would be aboard the bus if I were as short as the woman. The man was my height and could easily hold the bar over his head while he supported his girlfriend. When he received a phone call, he had to free up his arm and before long he was engaged in a mundane conversation that didn’t attract my attention.

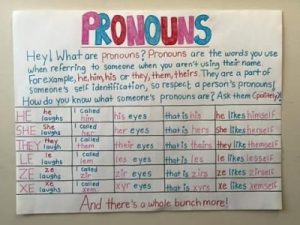

It was only when he had stopped the call and was explaining to his girlfriend that he’d just received a call from a woman who had transitioned from the man he’d known in school. He explained how he knew the woman, how when she transitioned he hadn’t been surprised, and they talked about whether his girlfriend—having attended the same school a few years earlier—knew him or her. He tended to mix up his pronouns, as he talked about the boy he’d known in school, and the woman he’d only  recently found on Facebook.

recently found on Facebook.

Suddenly, on the strength of her eavesdropping, the woman in front of me asked him if he were talking about ___. Once he confirmed that he was, with a rather surprised look on his face, she said, “That’s my wife.”

This began a short interaction about how Winnipeg was such a big small town in many ways and that such coincidences, although odd in other places, were a commonplace. She yanked hard over on the tiller of that conversation by demanding to know why her wife was calling him. I couldn’t see her face, and tell if her expression matched her tone, but she sounded suddenly jealous and suspicious. To his credit the man handled it well. He said he hadn’t heard from her or him in over a year, she corrected him to “her,” and after that suspicion was settled, he spoke about how they had bonded in high school.

The way he phrased that bonding was awkward, for he said they both excluded because he was bisexual and his friend thought of himself as a woman. The woman accepted that explanation, but couldn’t resist telling him that he shouldn’t be discussing another person’s transitioning so openly on the bus.

I was delighted by the entire interaction.  I liked it that the man I wouldn’t have thought to be so open minded was supportive of his transitioned friend, that the woman was so suspicious and judgemental, and that the conversation had taken to many strange tracks. He agreed with her, although I thought he was slightly taken aback that she was describing the parameters of his conversations with his girlfriend on public transit. That mollified her, and then they began a stilted conversation in which he flattered her by asking—since he was having such trouble with pronouns—whether he should call his friend he or she. She told him he should use she, and why she felt that to be the case.

I liked it that the man I wouldn’t have thought to be so open minded was supportive of his transitioned friend, that the woman was so suspicious and judgemental, and that the conversation had taken to many strange tracks. He agreed with her, although I thought he was slightly taken aback that she was describing the parameters of his conversations with his girlfriend on public transit. That mollified her, and then they began a stilted conversation in which he flattered her by asking—since he was having such trouble with pronouns—whether he should call his friend he or she. She told him he should use she, and why she felt that to be the case.

Before long her stop came up, and she exited the bus. The couple exclaimed after that Winnipeg was such a small place and the coincidence of her friend calling after a year while standing next to her wife was strange. I was so thrilled by the conversation that I couldn’t help but jump in. “I thought that conversation was going to go  very differently,” I said. “Especially with that whole, ‘Why is my wife calling you?’”

very differently,” I said. “Especially with that whole, ‘Why is my wife calling you?’”

“Yeah,” he admitted. “I thought the whole thing was about to go south.”

We continued the conversation about the woman’s tendency to correct him, and then drifted into how older people have difficulty accepting how notions of gender have expanded more lately. I told him that it is expected that people his age are more accepting, but that I am continually surprised by people my age who make it their business what other people think about their own bodies. We then discussed their study plans at university and college, and when they left the bus the man shook my hand and I said goodbye.

There is hope for the unsocialized people in the Canadian and American transit systems, but  such interactions are few and far between. Most people are more than satisfied to read the transit as something to be endured while they wait to get to a place where they will live, rather than a place where they are also living.

such interactions are few and far between. Most people are more than satisfied to read the transit as something to be endured while they wait to get to a place where they will live, rather than a place where they are also living.

In other countries, people use transit as a valuable moment to talk to a stranger. I have had people unburden on me as though they were in front of an unpaid counselor, and I’ve had others pick my brain for advice about their university career once they found out I teach at a university. Still others use the moment to satisfy their curiosity about how people live in other countries. In Winnipeg, few realize that they are shutting down more and more opportunities to converse with a stranger. They demand silence while watching a movie, ignore strangers while walking in the street and taking the bus, and eschew meeting another’s glance when killing time in a waiting room. As they slam more and more doors on possible social opportunities, they are driven to dating apps and social media platforms in order to feel as though they belong to a community.

They demand silence while watching a movie, ignore strangers while walking in the street and taking the bus, and eschew meeting another’s glance when killing time in a waiting room. As they slam more and more doors on possible social opportunities, they are driven to dating apps and social media platforms in order to feel as though they belong to a community.

I don’t want to be the voice of the older person who didn’t grow up with social media and therefore has a gut reaction that it is all wrong, for I scarcely want to return to scratching on the cave wall with charcoal and ochre just because that was good enough for hundreds of generations of my ancestors, but when I search for a model of socialized behaviour, I am drawn to that of other countries. Even in my classrooms, the international students are the ones who talk to those around them. They have spent their lives interacting, from the joint family living arrangements in

wrong, for I scarcely want to return to scratching on the cave wall with charcoal and ochre just because that was good enough for hundreds of generations of my ancestors, but when I search for a model of socialized behaviour, I am drawn to that of other countries. Even in my classrooms, the international students are the ones who talk to those around them. They have spent their lives interacting, from the joint family living arrangements in their home country to the dozens of friends they’ve made and lost on a daily basis. They have a skill set that Canadians would be wise to emulate, if they want to find a friend without an app, and a lover without a credit card.

their home country to the dozens of friends they’ve made and lost on a daily basis. They have a skill set that Canadians would be wise to emulate, if they want to find a friend without an app, and a lover without a credit card.