When I was a child the opening credits of the Wonderful World of Disney TV show portrayed a world as far away as the moon. Rather appropriately, it seemed to my young mind, animated creatures shared the stage with live actors from Disney’s magical kingdom, a place no one I knew had ever been, and from what I could tell, very probably didn’t exist.

The opening sequence showed a fantastic castle that seemed to defy gravity in its minarets and towers, and spectacular colours flowed from Tinkerbelle’s wand, although in the sixties and seventies most people watching that would have only seen it in black and white. With multiple shots and split screens, the entire panorama that Disney would provide the child sprawled on the screen. Puppets played with drawings, live actors dressed as fantasy figures and silhouettes and rousing military-inspired music released dreams larger than the boxes of balloons that clouded the Disney sky. For a child in rural Canada, the far away kingdom was no more real than television sports and news, or any one of a dozen popular sit-coms.

that seemed to defy gravity in its minarets and towers, and spectacular colours flowed from Tinkerbelle’s wand, although in the sixties and seventies most people watching that would have only seen it in black and white. With multiple shots and split screens, the entire panorama that Disney would provide the child sprawled on the screen. Puppets played with drawings, live actors dressed as fantasy figures and silhouettes and rousing military-inspired music released dreams larger than the boxes of balloons that clouded the Disney sky. For a child in rural Canada, the far away kingdom was no more real than television sports and news, or any one of a dozen popular sit-coms.

Disney occupies a very different place in the American child’s heart. For them, Disney’s magic kingdoms are as real as Orlando and Anaheim can make them. For them, the promise made to them by their television is more than borne out by the reality of cotton candy and lines, expensive tickets and crowds, caged  animals and animated cartoons, and the stifling of unions and the minimum wage conditions of its workers. Most of them make a pilgrimage to Disney at least once in their lives, and for many, they continue those trips into adulthood. For them Disney contains a kind of magic the opening credits sequence doesn’t show, and they are more than willing to drive for a day or more to shred their dollars for its invented world.

animals and animated cartoons, and the stifling of unions and the minimum wage conditions of its workers. Most of them make a pilgrimage to Disney at least once in their lives, and for many, they continue those trips into adulthood. For them Disney contains a kind of magic the opening credits sequence doesn’t show, and they are more than willing to drive for a day or more to shred their dollars for its invented world.

As adults, they explain that some of the venues can be enjoyed by those who are more mature, but the bruises they earn from the rides belie their statements. Like an avid amateur skier, who straps sticks to his or her feet in order to shriek their way down a manicured slope only to do it again and again as a machine hauls them to the top of the hill, the Disney advocate ignores an entire enterprise hidden behind the curtain. The adult Disney advocate pretends not to know this. They have purposefully given their money to the corporation in order that it continues its work. Setting aside what they have heard of labour abuses in the media, ignoring the very real ugliness of the theme parks, they determinedly thrust through the crowds to enjoy themselves, dragging their tired children behind them and pushing aside the elderly who clog up some of the lines. “I’ve earned this,” they say to themselves, as they peel twenties from the stack that represents months of hard work, “I deserve the right to play.”

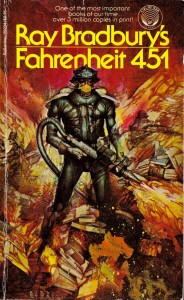

When Disney was at its heyday, Ray Bradbury asked in Fahrenheit 451 if we could go on playing as adults and ignoring the very real misery people around us. I think those adults who willingly and joyfully frequent Disney can answer that question now. We can.

When Disney was at its heyday, Ray Bradbury asked in Fahrenheit 451 if we could go on playing as adults and ignoring the very real misery people around us. I think those adults who willingly and joyfully frequent Disney can answer that question now. We can.