Although I usually have little  to say about the fripperies and pomp of pop music, once I watched Avicii’s “Wake Me Up” I was infuriated by its rather simplistic and classist portrayal.

to say about the fripperies and pomp of pop music, once I watched Avicii’s “Wake Me Up” I was infuriated by its rather simplistic and classist portrayal.

“Wake Me Up” is likely meant to tell the story of a woman and her daughter who feel out of place in the town where they live and how they are unhappy until they search for and find their real community. This seems innocuous enough, but the presentation of the mother and child as well as the villagers they are running from is more than problematic.

The mother is played by Russian fashion  model Kristina Romanova and the younger girl is the actress Laneya Grace. They do not in the least represent a downtrodden minority, for in their blond and blue-eyed way they are well dressed, engage in no work, and somehow keep a horse nearby which they do not bother to maintain. The world they run to is filled with people like themselves, young, beautiful, careless, mindlessly conformist, and who, as far as we can tell,

model Kristina Romanova and the younger girl is the actress Laneya Grace. They do not in the least represent a downtrodden minority, for in their blond and blue-eyed way they are well dressed, engage in no work, and somehow keep a horse nearby which they do not bother to maintain. The world they run to is filled with people like themselves, young, beautiful, careless, mindlessly conformist, and who, as far as we can tell,  live only for themselves and contribute nothing to society. They all share, in their conformist way, the same tattoo of two triangles facing away from each another, but they are scarcely a suffering and oppressed group—such as the gay people targeted by the Nazis who were made to wear a purple triangle. Rather they are happy, have the leisure to leap pointlessly about at a concert and, as the video shows, they are entitled to and remain unquestioned about their rather derisive view of their neighbours.

live only for themselves and contribute nothing to society. They all share, in their conformist way, the same tattoo of two triangles facing away from each another, but they are scarcely a suffering and oppressed group—such as the gay people targeted by the Nazis who were made to wear a purple triangle. Rather they are happy, have the leisure to leap pointlessly about at a concert and, as the video shows, they are entitled to and remain unquestioned about their rather derisive view of their neighbours.

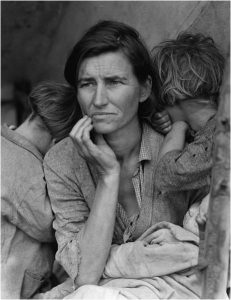

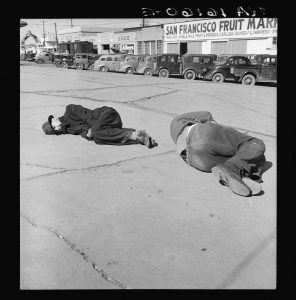

The neighbours are quite another matter. Perhaps so the contrast between them and the hipster mother and daughter can be delivered with a bludgeoning and unforgettable force, the neighbours are portrayed as trapped in the  dustbowl thirties. They could easily fit in with any of Dorothea Lange’s portraits of depression era sufferers. Their clothes are out of date, colourless and dirty, and their

dustbowl thirties. They could easily fit in with any of Dorothea Lange’s portraits of depression era sufferers. Their clothes are out of date, colourless and dirty, and their  posture is one of misery, despair, and anger. They are shown working with wooden crates and ash strip baskets that the directors must have scavenged from antique shops; no one has used those in at least fifty years. Their expressions are singularly grim, as though a

posture is one of misery, despair, and anger. They are shown working with wooden crates and ash strip baskets that the directors must have scavenged from antique shops; no one has used those in at least fifty years. Their expressions are singularly grim, as though a  score of drudges were let out of the prison where they had been kept since the thirties so that they could see everything that they were not able to be or have. The video is not in the least interested in them; they are given no voice, or even

score of drudges were let out of the prison where they had been kept since the thirties so that they could see everything that they were not able to be or have. The video is not in the least interested in them; they are given no voice, or even  variety of expression, although the video makes sure we are aware they represent black and white, old and young. What they most firmly represent, however, is the working poor. Just as the beautiful mother and equally beautiful daughter are meant to represent Avicii’s audience—young wealthy hipsters—the crowd that surrounds them in the street is the unhip, ugly, bestial side of America.

variety of expression, although the video makes sure we are aware they represent black and white, old and young. What they most firmly represent, however, is the working poor. Just as the beautiful mother and equally beautiful daughter are meant to represent Avicii’s audience—young wealthy hipsters—the crowd that surrounds them in the street is the unhip, ugly, bestial side of America.

The video presentation is as unsubtle as it is classist. The mother and daughter are given voice in the video, such as when the daughter suggests that they are not liked by their neighbours and then asks why. The mother, perhaps because the answer is a little too obvious, merely hugs her daughter’s plaint away. The video is not prepared to state its rather obvious conclusion: “They hate us because we are so much better than them in every way.”

To return to the only scene in which we see the two groups interact, we can see that the way the small family acts toward their poor neighbours is very different than the smiles the mother reserves for her new beautiful friends at the concert.  When the mother approaches her peers—as she obviously views them—she notes the tattoo which informs her they are her people, and then smiles at them and offers greetings. When she and the child walk through their neighbours, they wipe the smiles from their face and stare as though they were amongst dangerous zoo animals. Lest the viewer think that the mother and daughter are merely judgemental twits, the working poor neighbours are given the same stare and unsmiling faces.

When the mother approaches her peers—as she obviously views them—she notes the tattoo which informs her they are her people, and then smiles at them and offers greetings. When she and the child walk through their neighbours, they wipe the smiles from their face and stare as though they were amongst dangerous zoo animals. Lest the viewer think that the mother and daughter are merely judgemental twits, the working poor neighbours are given the same stare and unsmiling faces.  This is meant to convince us that the mother is in the right: “I don’t smile at them because they don’t smile at me.” Instead, they walk amongst the freakish poor as freaks themselves, everyone staring at the other, but in the ethos of the video, we are meant to know who to sympathize with.

This is meant to convince us that the mother is in the right: “I don’t smile at them because they don’t smile at me.” Instead, they walk amongst the freakish poor as freaks themselves, everyone staring at the other, but in the ethos of the video, we are meant to know who to sympathize with.

Once the mother rides away through the orchards on her horse to find her real people—the rich ravers at the concert—she returns to help her daughter escape. The horse is abandoned, as the daughter and her walk down the road dressed in even more funky clothing. They happily leave their neighbours behind, who are ostensibly working the orchards she rode through and taking care of her horse. The last scene is a shot of a poor, abused neighbour, carrying her wooden indigenous-made basket, turning away from the camera to continue her meaningless life now that her betters have left.

As an exercise in the portrayal of the working classes, the video is highly offensive. We know that hot only exists in reference to cold, but we scarcely need to experience zero degrees kelvin to know that something with less heat exists. Wealth is only defined by reference to poverty, but the video’s unsympathetic gaze reeks of unexamined privilege. We can understand that the video needs to write poverty as belonging to the dim past—to an America of the thirties—because otherwise the band might lose some of their own fan base, who live in poverty and spend their hard-earned money trying to emulate the lifestyle of the mother in the film. Even in the video, however, we can see that not everyone can merely dance their life away at a rave. Some people have to maintain the orchards, care for the abandoned horse, and maintain the roads the mother and daughter escape on.

The voiceless poor in the film, even in their exaggerated and archetypical presentation, are presumed to be single-minded, homogenous, angry, and judgemental of the beautiful. This is the poor written as the hateful other. Conveniently ignoring that the rhythms the rich are dancing to at the rave came from slaves and other musical traditions kept alive by downtrodden people, the video represents the working classes as mindless beasts that have nothing in common with the privilege of beauty and wealth which the video naturally combines.

The story of the mother and her daughter is as uninteresting as it is bland. Although I am curious about how the daughter came to be in the small town, what drab worker donated sperm to his better so that she might judge him later, and what they do for a living or how they manage to pay rent for their house, I am much more interested in the lives of those in the village. Are their resentful glances the result of having to maintain two useless members of their society, like the serfs of old supporting parasitic and superior aristocrats? What is their music like? What are their hopes and fears? They face a reality that is much more representative of the peoples of the world than the fraught anxiety of the mother and her daughter about not fitting in with people they despise, but what might the working classes in this video say if they had been given a voice?

If I were presented with the choice,  I would turn down the invite to the concert where the mother and her equally pretentious friends leap about and take selfies, and join the working poor, where the stories and art that keep culture alive find their wellspring.

I would turn down the invite to the concert where the mother and her equally pretentious friends leap about and take selfies, and join the working poor, where the stories and art that keep culture alive find their wellspring.