He tried to recover the salt air, the yelling men in the rigging, and the other piecemeal accoutrements of the nautical life.

He rarely imagined himself on a  whaler, although Moby Dick had taught him to expect the hardy meals of cabin bread and salt pork, the backslapping and desperation and fear of the breeching whale. Instead, he was on a ship of the line, by times ferrying passengers to the new world, watching the eager faces turned toward port as their dreams hovered just beyond a horizon that even they couldn’t see.

whaler, although Moby Dick had taught him to expect the hardy meals of cabin bread and salt pork, the backslapping and desperation and fear of the breeching whale. Instead, he was on a ship of the line, by times ferrying passengers to the new world, watching the eager faces turned toward port as their dreams hovered just beyond a horizon that even they couldn’t see.

The steamships also put in their appearances, and he’d been an oiler, running from shaft to shaft  with an oil can slippery with his sweat, or commanding others to crawl into holes while the massive engine idled, all potential energy pointed toward wreaking destruction but channeled into a narrow tube. The coal burners needed shovelers almost constantly, and he was black by the end of his shift, but above decks the white gloves of a steward covered the burn marks from sparking coals.

with an oil can slippery with his sweat, or commanding others to crawl into holes while the massive engine idled, all potential energy pointed toward wreaking destruction but channeled into a narrow tube. The coal burners needed shovelers almost constantly, and he was black by the end of his shift, but above decks the white gloves of a steward covered the burn marks from sparking coals.

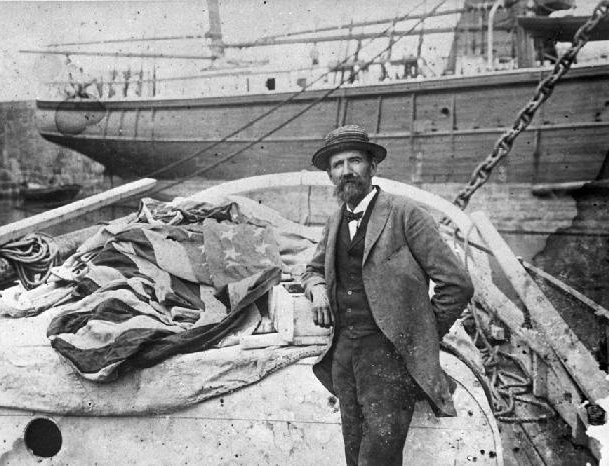

Sometimes he was a Joshua Slocum, recently vacating the naval yards for the smell of wood and tar. He turned in Slocum’s narrow bunk as the winds howled outside the port or near at hand canoes from the shore gingerly crept upon him in the night.

recently vacating the naval yards for the smell of wood and tar. He turned in Slocum’s narrow bunk as the winds howled outside the port or near at hand canoes from the shore gingerly crept upon him in the night.

Kon Tiki was also there, as he hauled in lines with half a dozen other bearded men, their girlfriends and wives forgotten in the thrash of the waves. He could see the broad desert that was the ocean, the lift and settle of the shack behind the heaving waves, and sense the Paul Gauguin greetings of native women, their limbs Tahitian brown and their breasts half uncovered while they laughed shyly behind their hand.

girlfriends and wives forgotten in the thrash of the waves. He could see the broad desert that was the ocean, the lift and settle of the shack behind the heaving waves, and sense the Paul Gauguin greetings of native women, their limbs Tahitian brown and their breasts half uncovered while they laughed shyly behind their hand.