Most people around the world marvel when American television shows feature street geography quizzes and Americans cannot point to a single country on a map. The subsequent discussion usually centres around the failing American education system, the geographical ignorance that citizens of powerful nations are allowed, and a squabble from the Americans themselves about cherry picking interviews and fake news. As impossible as it is to understand the thought processes of such people, I have often been intrigued by the blank slate of their interests or education.

My friend who worked in tourism had similar encounters with travellers who had no idea where they were. When she worked on Vancouver Island, RV-driving tourists would frequently claim that they’d arrived on the island by a causeway. With access to the island limited to a nearly two-hour ferry ride, she would usually argue with them.

similar encounters with travellers who had no idea where they were. When she worked on Vancouver Island, RV-driving tourists would frequently claim that they’d arrived on the island by a causeway. With access to the island limited to a nearly two-hour ferry ride, she would usually argue with them.

Once confronted, she told me, they would dig in their heels and demand that they’d driven onto the island. “That’s fine,” she would eventually accede. “Just make sure you take the causeway when you go home. Don’t take the ferry service.”

My friend Lisa worked in a call centre doing roadside assistance. Her job became more  involved and demanding when callers stranded beside their car could not describe where they were. Although they were frequently livid at her obstinacy when she didn’t immediately send a tow truck, Lisa was intrigued by what she saw as a mathematical word problem. If Train A is leaving Pittsburgh travelling at seventy kilometres an hour and passes Train B returning from Montreal at sixty kilometres an hour, at what point on the three hundred kilometre track will they cross?

involved and demanding when callers stranded beside their car could not describe where they were. Although they were frequently livid at her obstinacy when she didn’t immediately send a tow truck, Lisa was intrigued by what she saw as a mathematical word problem. If Train A is leaving Pittsburgh travelling at seventy kilometres an hour and passes Train B returning from Montreal at sixty kilometres an hour, at what point on the three hundred kilometre track will they cross?

Like many of us she’d encountered similar word questions in school, but she was suddenly asked to become proficient in calculation and surmise. She  would calm the irate customers, gently tell them that if she had no idea where they were, then she couldn’t send assistance and they might be stranded forever. The threat of being permanently off the grid would scare them into compliance and she could ask them to recall where they were going.

would calm the irate customers, gently tell them that if she had no idea where they were, then she couldn’t send assistance and they might be stranded forever. The threat of being permanently off the grid would scare them into compliance and she could ask them to recall where they were going.

She would then piece together what little the drivers knew, trying to isolate their particular dirt road. She used distance and time calculations, landmarks, and got to know tow truck drivers fairly well. She used skills she thought were long dormant, left over from strategy games such as Battleship, as she asked them where they lived, how long they had been driving, what direction they were going or, failing that, whether they were driving into or away from the sun. Some of them would remember a gas station “some time back,” or a cute boat sitting in a front yard. Others knew where they’d stopped at a McDonald’s and how the petting zoo across the street was closed.

Sorting through their scanty recollections and faulty guesses, she would finally send a tow truck in a direction, hoping that the driver was on pavement like they described—some people had to get out of the vehicle to check—or near the creek they’d possibly mislabelled a river. She spent hours using Google maps to find an Exxon station nowhere near a river, finding the wrong town, wrong county, wrong state.

described—some people had to get out of the vehicle to check—or near the creek they’d possibly mislabelled a river. She spent hours using Google maps to find an Exxon station nowhere near a river, finding the wrong town, wrong county, wrong state.

I had my own encounter with a similar geographical confusion and although the conversation happened more than twenty-five years ago, and I have long forgotten the particular towns and villages Loraine lived near or in, I remember her inability to describe where she lived and my shock at the implications of her confident ignorance.

When Loraine told me that she came from Florida, I asked her where in Florida. This conversational back and forth was meant to put her at ease more than grill her about her home, but the question backfired.

“I live in Turnipville,” she told me.

“What is that near?” I asked her.

“Potato town.”

“Any other places I might have heard of?”

“Broccoli Village, but that is small. Maybe Rhubarbton.”

“Are you near Miami? Or Jacksonville? Tallahasse?” I thought I would try the extreme south and north, as well as the capital, and in that way jog her memory.

She looked pensive for a moment and then shook her head. “I don’t think so.”

I grew more determined. “Orlando? You know, Disney World?”

“I’ve never gone there.”

“Are you on the Gulf Coast? Ever hear of Fort Myers? Tampa?”

“Of course I’ve heard of them.” She became testy at the suggestion.

I waited. “Are you near them?”

“Celeryton? That’s nearby.”

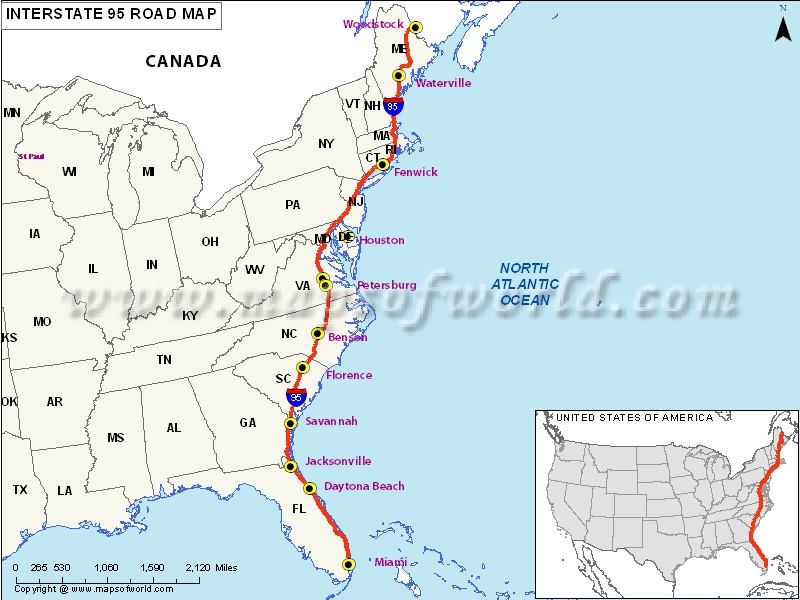

I started ticking off what cities I knew on my fingers, hoping one of them would startle her into awareness that she lived just beyond its borders. “Fort Myers, Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Tampa, Clearwater, Orlando, Daytona.”

Nothing.

“Jacksonville, Tallahasse,” I tried again.

She was confused by my persistence and I finally let it go, I simply had to admit that she’d somehow travelled to Canada from her home state of Florida  even though she had no idea where she lived in the greater Florida context. I imagined that she had merely told her local bus station that she wanted to go to Canada, and when she was buying a ticket in a larger centre, she mentioned New Brunswick, Canada.

even though she had no idea where she lived in the greater Florida context. I imagined that she had merely told her local bus station that she wanted to go to Canada, and when she was buying a ticket in a larger centre, she mentioned New Brunswick, Canada.

If she’d encountered someone like herself, they would have flummoxed, but with the bus system computers in front of them, they merely looked up where she needed to go and the system generated the needed tickets. They may have had no more idea where she needed to go than her. Going home would require a similar system. She would buy a ticket for Florida at the local Canadian bus station and the staff whose job it is to ensure their passengers arrive at their destination would get her to a city in northern Florida. From there, they would be able to search for her local village of Turnipville, and she would pay for the series of tickets which would rewind her journey back to her home.

Canadian bus station and the staff whose job it is to ensure their passengers arrive at their destination would get her to a city in northern Florida. From there, they would be able to search for her local village of Turnipville, and she would pay for the series of tickets which would rewind her journey back to her home.

The most startling aspect to the whole encounter for me was the impossibility of imagining how someone could blithely leave their home and not really know  where they lived. Her profound trust in the system—that the bus station workers would not send her to another Turnipville in another state—was horrifying. She did not care at all that she couldn’t describe where she lived. In fact, she was slightly derisive that I couldn’t locate Turnipville on my mental map without the extensive assistance of how close she lived to a city.

where they lived. Her profound trust in the system—that the bus station workers would not send her to another Turnipville in another state—was horrifying. She did not care at all that she couldn’t describe where she lived. In fact, she was slightly derisive that I couldn’t locate Turnipville on my mental map without the extensive assistance of how close she lived to a city.

I was reminded of the early wanderers in human history, who travelled the by-times-dangerous Silk Road or traded between the Mound Builder culture of the Americas. Without a map, operating sometimes only on stories, those brave and curious early travellers crossed invisible borders, had to cope with new customs and rules, and still persisted in knitting early human culture together by reaching out to their neighbours.

That was an easier task for the Australian  Aborigines, who followed the songlines or dreamlines of their ancestors. The ancient songs dictated the directions or travel, landmarks, the language varied with local languages, and travellers along the songlines were protected by the obligations of all peoples to the sacred nature of the journey. Despite much of the interior resembling a trackless waste,

Aborigines, who followed the songlines or dreamlines of their ancestors. The ancient songs dictated the directions or travel, landmarks, the language varied with local languages, and travellers along the songlines were protected by the obligations of all peoples to the sacred nature of the journey. Despite much of the interior resembling a trackless waste, it is crisscrossed with a cognitive and cultural map which both brings the land to life, identifies important landmarks, and provides safe travel for the Aborigines along the routes.

it is crisscrossed with a cognitive and cultural map which both brings the land to life, identifies important landmarks, and provides safe travel for the Aborigines along the routes.

In many ways, those ancient travellers still walk amongst us. They have the benefit of maps and GPS, but are drawn instead to the adventure. Like the early wanderers relied on their gods to help them and cried to the sky when they were in trouble, the modern motorist cries into their phone. Without knowing where they are or where they were going, they hope to still be saved.

and GPS, but are drawn instead to the adventure. Like the early wanderers relied on their gods to help them and cried to the sky when they were in trouble, the modern motorist cries into their phone. Without knowing where they are or where they were going, they hope to still be saved.

Perhaps the internet, with Google map services and blogs devoted to famous spots along each route, is the modern traveller’s songline. Rather than trouble themselves to learn the song, and thus walk it out across the land, they instead play catch up when they are lost by calling upon the internet as a depository of human geographical knowledge.  With their god on speed dial, they reject having to learn the songline themselves, and hopefully the system will continue to protect the tourists in the RVs, the motorist by their stalled engine on the pavement, and Loraine as she tries to find her home while ignoring a bewildering wilderness of place names and locations.

With their god on speed dial, they reject having to learn the songline themselves, and hopefully the system will continue to protect the tourists in the RVs, the motorist by their stalled engine on the pavement, and Loraine as she tries to find her home while ignoring a bewildering wilderness of place names and locations.