We often presume that someone who doesn’t care about their environment is merely ignorant. They just don’t know, we say to ourselves when pondering the person throwing recyclables in the trash, or making arguments about buying a larger vehicle. If they knew the implications  of their actions, they would act differently.

of their actions, they would act differently.

That argument may salve our own moments of hypocrisy, but in larger terms it doesn’t stand up to even the most basic scrutiny. People who have very little formal or informal education can act in ways that suggest they are considering the environment, and some who are highly educated think only of themselves.

When I was in graduate  school working on my Masters, I was struck by the behaviour of my fellow graduate students in terms of what they knew and what they found acceptable. Each three-hour class they would file in with their drinks in aluminium cans, bottles, and recyclable coffee cups. They would drink these over the course of the first half of the class, and then pitch the recyclable containers into the trash on the way out the door to buy more.

school working on my Masters, I was struck by the behaviour of my fellow graduate students in terms of what they knew and what they found acceptable. Each three-hour class they would file in with their drinks in aluminium cans, bottles, and recyclable coffee cups. They would drink these over the course of the first half of the class, and then pitch the recyclable containers into the trash on the way out the door to buy more.

Although I had initially been a fan of the argument that such people were too ignorant to understand the full impact of their behaviour, I was now confronted with evidence that an educated person was equally reckless. I watched as week after week my fellow students did exactly the same thing, presumably to save themselves a walk down the  hall to the recycle bin. They knew better, and in fact could be quite vociferous about environmental matters, but when it came to their views affecting their behaviour, they were more reluctant to change. As much as any science-denier who claims that global warming is a hoax, condensation trails are laced with chemicals, fluoride is a mood-altering substance having nothing to do with dental care, and that people have been lying for thousands of years about the earth’s shape, age, and origin, these much more educated graduate students had decided that their momentary inconvenience was not worth the planet on which they lived.

hall to the recycle bin. They knew better, and in fact could be quite vociferous about environmental matters, but when it came to their views affecting their behaviour, they were more reluctant to change. As much as any science-denier who claims that global warming is a hoax, condensation trails are laced with chemicals, fluoride is a mood-altering substance having nothing to do with dental care, and that people have been lying for thousands of years about the earth’s shape, age, and origin, these much more educated graduate students had decided that their momentary inconvenience was not worth the planet on which they lived.

Like the global warming denier, they were primarily concerned with having to change their lives in one small aspect, and although they would not take to the textbooks to prove that their actions were inconsequential, they were every bit as lazy and self-serving as any fundamentalist who had decided that his or her book was more true than every bit of scientific research done in human history. My fellow students were even more cynical than a flat earth proponent, for if cornered, all they could point at to support their actions was their indifference. Although they might give lip service to environmental questions, they did not care to follow them up with changing their behaviour.

At least the fanatic who claims the earth was six thousand years old is caught in the desperate straits between their religious book and the real world, but my graduate students could not make the same plea. They had no platform they could point to, no theory to which they ascribed; they just didn’t care enough to make a change.

Watching them behave this way every week drove home the understanding that hitherto I had found difficult to see. Environmental consciousness has much more to do with whether someone is prone to understanding that their way of living affects the planet and others on it and that their actions or inactions have real-world consequences, and less to do with whether they know how much carbon their local transit expels. You may teach about the Pacific garbage patch, but encouraging someone to get past their pacific indifference is a different matter.

that their way of living affects the planet and others on it and that their actions or inactions have real-world consequences, and less to do with whether they know how much carbon their local transit expels. You may teach about the Pacific garbage patch, but encouraging someone to get past their pacific indifference is a different matter.

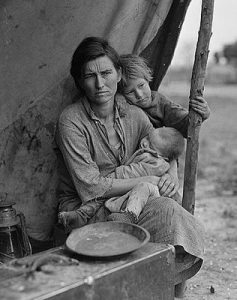

Education may not automatically lead to action, any more than ignorance guarantees inaction. The choices that people make have less to do with what they understand and how much they care about something outside themselves.  The uneducated person who grew up in the Great Depression had learned a form of parsimony that remains much more environmental than most modern consumers who buy cotton t-shirts promoting free trade, and insist on transferring their drinks to reusable containers that they buy new every few weeks. The depression-era farmer composted, or fed food scraps to the pigs, bought as little as possible, and fixed everything from a cloth flour bag to farm machinery rather than buying new. They may have been forced to this pass because of penury, but their concern with waste is as instructive today as it was during their time.

The uneducated person who grew up in the Great Depression had learned a form of parsimony that remains much more environmental than most modern consumers who buy cotton t-shirts promoting free trade, and insist on transferring their drinks to reusable containers that they buy new every few weeks. The depression-era farmer composted, or fed food scraps to the pigs, bought as little as possible, and fixed everything from a cloth flour bag to farm machinery rather than buying new. They may have been forced to this pass because of penury, but their concern with waste is as instructive today as it was during their time.