Although student papers are not the gold mine that some websites suggest,  with anti-pedantic-teacher rhetoric and unlikely yet comical meanings, they sometimes offer thoughtful analysis and clever observations. These are a delight for the instructor, but unfortunately—and perhaps this says something about the profession—they rarely inspire dissection and commentary. Sometimes, sadly, a particular sentence or argument will stand out much more than merely good writing, because the argument has implications that the student may not have intended, or because they have juxtaposed words that do not easily combine to make a sentence, and those are worth a second look.

with anti-pedantic-teacher rhetoric and unlikely yet comical meanings, they sometimes offer thoughtful analysis and clever observations. These are a delight for the instructor, but unfortunately—and perhaps this says something about the profession—they rarely inspire dissection and commentary. Sometimes, sadly, a particular sentence or argument will stand out much more than merely good writing, because the argument has implications that the student may not have intended, or because they have juxtaposed words that do not easily combine to make a sentence, and those are worth a second look.

In my latest set of papers I came across a sentence that was mundane enough at first glance, but rapidly—as if it were hurrying toward its denouement—it became ripe with likely unintended connotations: “What we learned from this is if we keep advancing with technologies like this we will end up with a world that will deteriorate faster than an orange left outside for a while.”

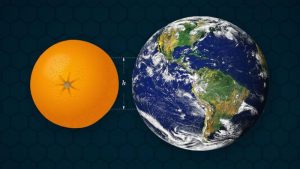

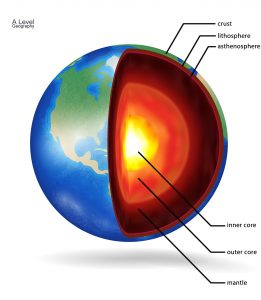

This splendid example of vagueness—“this” does not become more clear in context—is capped by the strangely elegant and ultimately unsatisfying analogy  about a rotting orange. If we ignore the students’ rather commonplace statement about the effect of technology upon the unspecified but negative state of the planet, we are instantly drawn to the tension between the two globes and what will eventually happen to them.

about a rotting orange. If we ignore the students’ rather commonplace statement about the effect of technology upon the unspecified but negative state of the planet, we are instantly drawn to the tension between the two globes and what will eventually happen to them.

Technological advancement will inevitably cause the planet to deteriorate—that seems clear enough—although the way the planet will be affected is less than clear. The sentence could have easily ended there: “What we learned from this is if we keep advancing with technologies like this we will end up with a world that will deteriorate.” Without the comparison of the Earth to an orange the sentence is merely trite and slightly incoherent. Once we slice off that final piece, however,  we lose the comparative rate at which the Earth will deteriorate as well as the delightful figure of the orange. Losing the comparison’s sense of speed is more than problematic, for grammatically that is the main point the sentence is hurrying toward, but the slow deterioration of the orange is more inviting.

we lose the comparative rate at which the Earth will deteriorate as well as the delightful figure of the orange. Losing the comparison’s sense of speed is more than problematic, for grammatically that is the main point the sentence is hurrying toward, but the slow deterioration of the orange is more inviting.

If we do not have the final part of the sentence, we would lose the rather visceral comparison of a large planetary body to a rotting orange. The student  likely realized that the descriptive quality of their sentence was insufficient, so rather than be accused of being vague about the effects of technology, they tacked on the figure of the orange. Unfortunately, if clarification is indeed what they were interested in, the orange adds little to what we can guess about the deterioration of the planet. Instead, we are left wondering what will happen to the orange.

likely realized that the descriptive quality of their sentence was insufficient, so rather than be accused of being vague about the effects of technology, they tacked on the figure of the orange. Unfortunately, if clarification is indeed what they were interested in, the orange adds little to what we can guess about the deterioration of the planet. Instead, we are left wondering what will happen to the orange.

The comparison is somewhat apt in at least one way. Both an orange and the planet are rough spheres. One is much larger than the other, however, and is made of rock  and metal that does not easily putrefy. As well, whatever we might imagine happening to an orange “outside” for a “while,” it would not likely be experienced by the Earth in the same way. The image does not work in any fashion that the reader can imagine, and thus the comparison is unable to do the hard work of describing what is going to happen to the Earth under the influence of technology.

and metal that does not easily putrefy. As well, whatever we might imagine happening to an orange “outside” for a “while,” it would not likely be experienced by the Earth in the same way. The image does not work in any fashion that the reader can imagine, and thus the comparison is unable to do the hard work of describing what is going to happen to the Earth under the influence of technology.

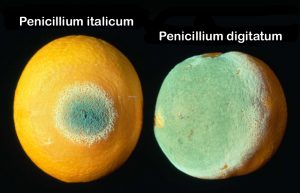

Both the rate at which the Earth will deteriorate, which is the point of the comparison, and the type of deterioration we might expect, are rather unhelpfully supported by the vague statement of where the orange is doing its putrefaction. It is “outside.” If we presume—and I think we are meant to do—that inside is a house, then outside varies greatly depending on the time of year and location. My student wrote this in the winter, and outside ranges into the minus double digits, which means that the orange would be frozen solid and therefore suffer not at all, at least until spring. If my student meant to make a more general reference to outside, then the orange’s fate is even more difficult to ascertain. In the summer a raccoon might make off with the orange, in my city a homeless person might be hungry enough to risk it, and certainly ants and other insects could see it as a tasty snack. In the tropics the orange might desiccate or mould before it is devoured, although an insect attack might be even more concerted and profound. In the fall or early spring in my city the orange would likely remain perfectly preserved for weeks at a time. Rather obviously, the orange’s ambiguous status gives no sense of what is going to happen to the Earth under the influence of technology.

on the time of year and location. My student wrote this in the winter, and outside ranges into the minus double digits, which means that the orange would be frozen solid and therefore suffer not at all, at least until spring. If my student meant to make a more general reference to outside, then the orange’s fate is even more difficult to ascertain. In the summer a raccoon might make off with the orange, in my city a homeless person might be hungry enough to risk it, and certainly ants and other insects could see it as a tasty snack. In the tropics the orange might desiccate or mould before it is devoured, although an insect attack might be even more concerted and profound. In the fall or early spring in my city the orange would likely remain perfectly preserved for weeks at a time. Rather obviously, the orange’s ambiguous status gives no sense of what is going to happen to the Earth under the influence of technology.

The last part of the orange’s destiny is left to the vague word “while.” Unfortunately, even though the entire figure is meant to describe how quickly the Earth will deteriorate—which is “faster” than the orange—we have no idea how quickly the orange will rot. And, if that vagueness were not imprecise enough, the rate of deterioration is never specified although the timing of the changes is apparently significant to the sentence. The orange is left outside, subject to unspecified climatic conditions, for an unspecified amount of time.

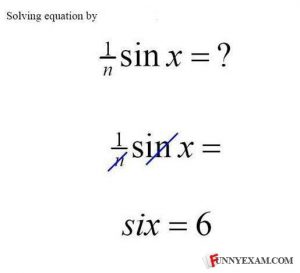

The only certainty we gain from the comparison is that whatever is going to happen to the orange for however long, is slower than what is happening to an Earth subject to the influence of technology. This comparison is like a poorly formed math question that asks for a value to x yet refuses to give enough information that it can be calculated (x is equal to 3 times y – 17). Without knowing at least one of the factors, the comparison becomes meaningless, at least if the sentence is parsed in this fashion.

a poorly formed math question that asks for a value to x yet refuses to give enough information that it can be calculated (x is equal to 3 times y – 17). Without knowing at least one of the factors, the comparison becomes meaningless, at least if the sentence is parsed in this fashion.

We only know—from the sentence if not from statements about pollution and climatic shifts—that the deterioration happening to the planet is rapid, but we are left floundering as to how swiftly technology will affect the Earth. Finally, the status of the Earth unknown, we turn our confusion to what is happening to what the sentence describes as a kind of Schrödinger’s orange. In this way the student has captured our ignorance about the world’s deterioration better than any definitive but ultimately inaccurate statement about what is happening to the planet.

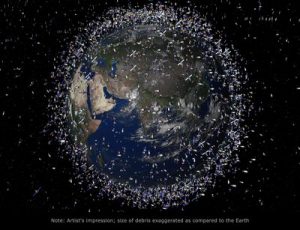

We will never be able to know exactly the orange’s condition any more than we can fully describe what is going to happen to the Earth as a result of our technological prowess. There are simply too many variables. In that way, my student’s figure of speech is much more perceptive than it first appears. The multiplicity of factors that affect the planet are simply too complex to model. We might be able to calculate rainfall patterns and heat absorption, but we cannot hope to integrate that with the effect of upper-atmosphere aerosols, plastic in the oceans reflecting heat, ash and dust on ancient glaciers leading to a faster melt, die-off of plankton and reefs which absorb carbon dioxide, clearcutting and subsequent erosion and how that diminishes the planet’s ability to capture carbon. Those exceedingly complicated effects with a million changing variables are likely impossible to fully capture or understand. In that way, the student is correct: “What we learned from this is if we keep advancing with technologies like this we will end up with a world that will deteriorate faster than an orange left outside for a while.”

Even if we don’t know how long it will take, we know that what is happening to the orange is not good; we know that the orange will likely be inedible at the end of the procedure, and when the fate of the orange has run its course, we can guess that we are to blame. In that way, the student has precisely, if metaphorically, described the present state of our knowledge about our effect on the planet as well as the nature of our responsibility in the matter. If we had taken better care of the small globe then it might sustain us another day, and likewise, if we take better care of the larger one, it might sustain us into the future.

if metaphorically, described the present state of our knowledge about our effect on the planet as well as the nature of our responsibility in the matter. If we had taken better care of the small globe then it might sustain us another day, and likewise, if we take better care of the larger one, it might sustain us into the future.