Most news, internet search, and social media platforms have optimized their offerings to suit what their viewers most frequently choose to see. That makes sense in terms of ad dollars, for they want to have a targetable  demographic, but as we have learned from similar capitalist reasoning, what is best for the market is not always best for society.

demographic, but as we have learned from similar capitalist reasoning, what is best for the market is not always best for society.

Every time there is a mass shooting in the United States, there is much breast-beating about the identity of the shooter. Then, inevitably, it is reported that the  gunman—the gender assignation is deliberate—is a white man whose white supremacist ideals encourages him to hate gay people, Jews, Blacks, human rights, Muslims, or any other group that he can easily target despite his general lack of education. Usually that discovery brings about a wave of news stories about how we are living in social media echo chambers, and that the great mass of people are getting their ideas about the world, their news even, from posts that their friends send them on Facebook or Twitter. This echo chamber means that they only see olds, and that anything which is news is invisible because they have never expressed an interest in such material in the past.

gunman—the gender assignation is deliberate—is a white man whose white supremacist ideals encourages him to hate gay people, Jews, Blacks, human rights, Muslims, or any other group that he can easily target despite his general lack of education. Usually that discovery brings about a wave of news stories about how we are living in social media echo chambers, and that the great mass of people are getting their ideas about the world, their news even, from posts that their friends send them on Facebook or Twitter. This echo chamber means that they only see olds, and that anything which is news is invisible because they have never expressed an interest in such material in the past.

A search for “social media echo chamber” on Google Scholar—another echo chamber in its own corporate right—returns seventy-nine results, and many more pundits and more serious media watchdogs and analysts have written articles which are not included in that list. The phenomenon is well known, but as a culture we don’t see an easy way out of such a conundrum. That is partially because we have a policy to let corporations do what they want.

A search for “social media echo chamber” on Google Scholar—another echo chamber in its own corporate right—returns seventy-nine results, and many more pundits and more serious media watchdogs and analysts have written articles which are not included in that list. The phenomenon is well known, but as a culture we don’t see an easy way out of such a conundrum. That is partially because we have a policy to let corporations do what they want.

Historically,  newspapers were organs of corporate interests similar to modern social media sites, and many argue that is still the case in the corporate media, but the small town papers and radio usually compensated for the worst of that myopia. Now social media platforms reach vast numbers of people, and even without deliberate tinkering with what people see—such as targeted ads from those who have bought the advertising space and other nations interfering with what the citizens in their crosshairs learn about the world—such platforms wield immense power over the development of the culture.

newspapers were organs of corporate interests similar to modern social media sites, and many argue that is still the case in the corporate media, but the small town papers and radio usually compensated for the worst of that myopia. Now social media platforms reach vast numbers of people, and even without deliberate tinkering with what people see—such as targeted ads from those who have bought the advertising space and other nations interfering with what the citizens in their crosshairs learn about the world—such platforms wield immense power over the development of the culture.

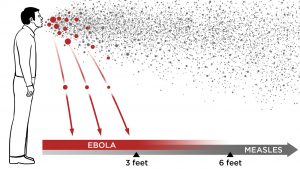

The social media echo chamber operates like a kind of secular religious indoctrination,  and its effect on education is similar. Religion is a kind of virus—in that it is easily transmittable and generally interferes with the full functioning of the person—but its effect is generally limited to one aspect of a person’s life. Educational material is a different matter, which is why the churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples in many countries are so eager to take over their school curriculums. They are well aware that if they can control the educational system then can control what people think. Now that social media platforms have become so ubiquitous,

and its effect on education is similar. Religion is a kind of virus—in that it is easily transmittable and generally interferes with the full functioning of the person—but its effect is generally limited to one aspect of a person’s life. Educational material is a different matter, which is why the churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples in many countries are so eager to take over their school curriculums. They are well aware that if they can control the educational system then can control what people think. Now that social media platforms have become so ubiquitous,  they have even more widespread power. Just as our education system is failing, self-education through the internet is stepping in to fill the gap, but the generally uninformed populace—whose notion of critical thinking is whether the view agrees with their own—is easily led by the echo chambers they are trapped inside.

they have even more widespread power. Just as our education system is failing, self-education through the internet is stepping in to fill the gap, but the generally uninformed populace—whose notion of critical thinking is whether the view agrees with their own—is easily led by the echo chambers they are trapped inside.

Although the way out of this conundrum doesn’t seem possible, I would caution us to step farther back from our hands-off way of interacting with corporations and to return to an earlier notion of education. Although there are those who want to control the education system because that means social control, a general education, as it was first envisioned—and we can see some of those ideals discussed in  H. G. Wells’ World Brain—were about giving the citizen verified information about the world in order that they could contribute to society as a whole. The traditional notion of education wasn’t about leading the citizen to information in order to earn money from their interest. That is why we must ask the social media platforms to become better citizens and stop thinking only of their bottom line. Although it goes against their mandate, they must consider that they have—rather inadvertently—taken over the education of the citizenry, and that such a responsibility cannot operate on the basis of mere mercenary concerns about profit.

H. G. Wells’ World Brain—were about giving the citizen verified information about the world in order that they could contribute to society as a whole. The traditional notion of education wasn’t about leading the citizen to information in order to earn money from their interest. That is why we must ask the social media platforms to become better citizens and stop thinking only of their bottom line. Although it goes against their mandate, they must consider that they have—rather inadvertently—taken over the education of the citizenry, and that such a responsibility cannot operate on the basis of mere mercenary concerns about profit.

They must begin—and I think this will have to happen slowly at first—to modify their algorithms so that people see posts from outside their stated interests.  The elder who is interested in Alzheimer’s research should also be learning about video games for kindergarteners, and the right-wing nationalist should learn about the rest of the world. The Justin Bieber fan should be subject to Tom Waits links, and the ballerina should sit through some Mongolian throat singing. These modifications of the algorithms should be done slowly, at first, so that those more closed communities don’t at first realize that they are being educated, but as their horizons expand, they should learn more and more. This will inevitably affect their ability to make a profit, but it’s worth remembering that they already earn billions of dollars. I don’t think they can avoid losing a fraction of that profit, but they can still advertise to a broader spectrum of customer or shift with the changing times. When the internet was new the corporate concerns hadn’t yet learned how to capitalize on it, but before long they realized that they could control what advertising their users saw. I have faith that the endlessly malleable nature of corporate enterprises can rise to this new challenge.

The elder who is interested in Alzheimer’s research should also be learning about video games for kindergarteners, and the right-wing nationalist should learn about the rest of the world. The Justin Bieber fan should be subject to Tom Waits links, and the ballerina should sit through some Mongolian throat singing. These modifications of the algorithms should be done slowly, at first, so that those more closed communities don’t at first realize that they are being educated, but as their horizons expand, they should learn more and more. This will inevitably affect their ability to make a profit, but it’s worth remembering that they already earn billions of dollars. I don’t think they can avoid losing a fraction of that profit, but they can still advertise to a broader spectrum of customer or shift with the changing times. When the internet was new the corporate concerns hadn’t yet learned how to capitalize on it, but before long they realized that they could control what advertising their users saw. I have faith that the endlessly malleable nature of corporate enterprises can rise to this new challenge.

In order to transcend the echo chamber, our weakening education system, and the arbitrary corporate control over what we see, we need the social media corporations to realize that their job has shifted. They are now—whether they are prepared for it or not—in the education business, and they need to respond accordingly. They need to fight their board of directors for whom business as usual is profit at all costs, and learn to measure the greater social cost of avarice. In a society where many people are shooting their neighbours, they will quickly run out of customers, so like a virus they need to occupy the host but not kill it if they hope to have a market share in the future.

If they can make this change,  the more stable future they create will help them shift to their next market. Likely, if the current trend continues, social media platforms, or some similar information delivery system is the future of instruction, and those corporations which make the shift now will be in the vanguard.

the more stable future they create will help them shift to their next market. Likely, if the current trend continues, social media platforms, or some similar information delivery system is the future of instruction, and those corporations which make the shift now will be in the vanguard.