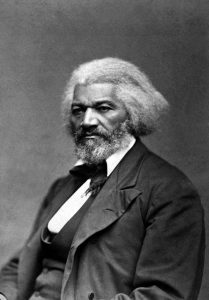

Although I have read many great student sentences over the years, probably the most memorable one is from my student’s essay when I was teaching in the United States.  One of my students was writing about Frederick Douglass, the famous former slave, orator, and abolitionist, but the grammar of their essay turned against them and they ended up saying something very different from what they likely intended.

One of my students was writing about Frederick Douglass, the famous former slave, orator, and abolitionist, but the grammar of their essay turned against them and they ended up saying something very different from what they likely intended.

Although I have since—after many thousands of pages of marking—forgotten the paper itself, I remember the sentence: “Not only was Frederick Douglass a slave, but he had to work for long hours for low pay and frequent beatings.” They were right about some of their assertions. Frederick Douglass (born February 1818 – February 20, 1895) had been a slave in Maryland before he escaped to become the famous agitator for both black and women’s rights. Also, Douglass was frequently beaten; the student was right about that as well. As far as low pay, it is true that “low”  does not begin to describe how poor was the remuneration for slave work.

does not begin to describe how poor was the remuneration for slave work.

It is worth considering the sentence more carefully, however. Looking it over for more than its mistakes, it can be found to raise interesting albeit problematic questions. The beginning, “not only” makes the first clause subordinate, and implies that whatever follows will either build upon or supersede the initial statement: “Frederick Douglass a slave.” The reader is thus prepared for some other pieces of information related to his slavery but also possibly other portions of his life that inform his slavery or slavery in general.

The information the reader receives is not entirely expected. The notion of the student,  who—and perhaps this speaks rather highly of their moral sense if not their understanding of slavery—believes that slavery is a paying position, is likely due to modern idiomatic usage of the term. People who have to work for long hours, frequently complain, “I worked like a slave all day,” and when they mention mistreatment, they say, half tongue-in-cheek, “what am I, a slave?” Thus the student, who likely works for “slave

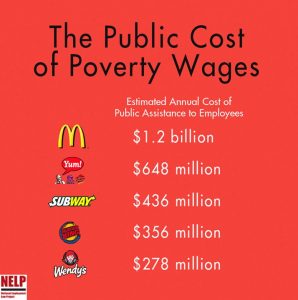

who—and perhaps this speaks rather highly of their moral sense if not their understanding of slavery—believes that slavery is a paying position, is likely due to modern idiomatic usage of the term. People who have to work for long hours, frequently complain, “I worked like a slave all day,” and when they mention mistreatment, they say, half tongue-in-cheek, “what am I, a slave?” Thus the student, who likely works for “slave  wages,” or minimum wage, has probably heard the expression applied to work like their own. As well, they may well find it impossible to imagine someone being forced to work for nothing, although the American Japanese internment camps, as well as the work camps of the Nazis, are there to disabuse them of the notion.

wages,” or minimum wage, has probably heard the expression applied to work like their own. As well, they may well find it impossible to imagine someone being forced to work for nothing, although the American Japanese internment camps, as well as the work camps of the Nazis, are there to disabuse them of the notion.

In modern times, this type of work is done by people with intellectual disabilities, who are sometimes hired for an extremely low government-paid stipend, although many of them may be more than capable than doing a day’s work. In that case they are merely being taken advantage of by unscrupulous employers (surely a tautology)

this type of work is done by people with intellectual disabilities, who are sometimes hired for an extremely low government-paid stipend, although many of them may be more than capable than doing a day’s work. In that case they are merely being taken advantage of by unscrupulous employers (surely a tautology)  who are abusing a system set up for people whose work skills do not add value in the traditional sense. Other forms of free labour that are common in society would be the demand for long unpaid, training periods for new workers, and the volunteer experience people are expected to use to pad their resume.

who are abusing a system set up for people whose work skills do not add value in the traditional sense. Other forms of free labour that are common in society would be the demand for long unpaid, training periods for new workers, and the volunteer experience people are expected to use to pad their resume.

It is to the student’s credit that they found working for nothing hard to imagine, although it speaks volumes about how their education system failed them in terms of describing a major component of their own history. Note as well that his hours were “long,” which indicates the student is further noting the unfairness of the system.

Where the grammar gets increasingly strange is when the student considers the other part of Douglass’ pay. He works for “low pay” and “frequent beatings.” Although the use of the and is likely the an inadvertent result of the student’s prose getting away from them, the he or she has implied that Douglass was partly paid in beatings. Perhaps that was meant to make up  for the lowness of the pay, but whatever the result, it begs the question of whether he would have been willing to take more pay and less beatings, or whether the frequency of the beatings is meant to be a positive aspect of his pay system. He was paid regularly and beat frequently, which perhaps in the mind of the student is better than being paid on no set schedule and being constantly surprised by sudden and unplanned beatings.

for the lowness of the pay, but whatever the result, it begs the question of whether he would have been willing to take more pay and less beatings, or whether the frequency of the beatings is meant to be a positive aspect of his pay system. He was paid regularly and beat frequently, which perhaps in the mind of the student is better than being paid on no set schedule and being constantly surprised by sudden and unplanned beatings.

The second and principal clause is where the sentence gets the strangest, but because of that it encourages the reader to forget that it is meant to supplement the statement made in the initial clause. “Not only” was he a slave, Douglass also had to be a slave. The statement implies that the student has a more uncertain notion of slavery than the reader might initially suppose. Although there are many more components to slavery, like denial to due process under the law, inability to own property, denial to medical care, inability to travel without permission, and say, “being owned,” the main idea that would come into the reader’s mind upon reading about Douglass being a slave was that he would be mistreated and likely had to work. The student reads this as somehow exacerbating Douglass’ slave status.

In a way, the student’s naiveté about slavery, and the mistreatment of his or her fellow citizens, or the people who would become his or her fellow citizens after emancipation, is endearing. They find the horror of the institution of slavery so impossible to understand that they cannot imagine even its more basic features, no pay for work and beatings, were an established part of the system of inequality. In terms of their sentence, however, they let the comma fool them into thinking that the two parts of the sentence were independent, instead of the reality of their grammar, that they were intimately connected and commented on one another. Also, they were seemingly unaware that the “and” meant they were listing two items which were equal under the umbrella that they had chosen to construct. The “long hours” Douglass had to work, once “low pay” entered the agreement and was followed by an “and,” meant that both items in the list were included in the pay.

This exercise is meant to be about more than denigrating student writing. The internet is rife with statements about students’ essays, and although most of them appear to be created on the spot by writers experienced in denigrating the abilities of others, I am more interested in how the student’s words got away from them, and thus were able to enjoy a life of their own frolicking on the grass of meaningless and illogic. This can happen to any of us, those who write for a living and are apparently aware of how a collection of words together in a string might mean something more or less than we intend.

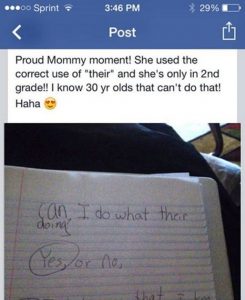

More recently, online grammar  guardians seem to easily find any misuse of “their” and “they’re” riveting and the cause for hilarity, and they are cheered on by those for whom schadenfreude is a delight. But to engage in such fish-in-a-barrel target practice does not excuse us from the slippery world of the signifier’s loose relationship with the signified. Those who delight in the low hanging fruit of misspellings and the confusing of adjectives with nouns, lose track of the slightly more subtle problems that can arise in our sentences and entirely contravene what we mean to say.

guardians seem to easily find any misuse of “their” and “they’re” riveting and the cause for hilarity, and they are cheered on by those for whom schadenfreude is a delight. But to engage in such fish-in-a-barrel target practice does not excuse us from the slippery world of the signifier’s loose relationship with the signified. Those who delight in the low hanging fruit of misspellings and the confusing of adjectives with nouns, lose track of the slightly more subtle problems that can arise in our sentences and entirely contravene what we mean to say.

This problem of expression is one that we all share, and first year students are no exception. As if the language is actively conspiring against us, words change their meaning, idiomatic utterances spring to life only to seem dated and trite a few years later, and new coinages astound with their obtuseness or utility. Even if we insist on reading grammar as no more than the rules that define how words form a chain of meaning, that does not mean the words will not conspire against us and link themselves to other thoughts almost of their own accord.