Many years ago I found myself trying to explain the movement of the sun during the winter to a class in Victoria, British Columbia, and ever since I have been struck by how cultural knowledge can be allowed or disallowed by geography. If you try to explain snow, for instance, to someone from the Cook Islands  in the central South Pacific—as I did when I was teaching there—you receive blank stares. My students understood the notion of frost and ice, for some islanders had freezers for the preservation of fish, but when I tried to describe how my entire country

in the central South Pacific—as I did when I was teaching there—you receive blank stares. My students understood the notion of frost and ice, for some islanders had freezers for the preservation of fish, but when I tried to describe how my entire country sits beneath a blanket of such a substance, they agreed just to be polite.

sits beneath a blanket of such a substance, they agreed just to be polite.

When I tried to imagine the Atacama Desert before I went there this past summer, I was in a similar situation. I never imagined that the desert would be so completely dead. I was surprised that I could stand  amongst the rocks and sand and not see a single living thing. Not a bug or weed or fly managed to live in such a desiccated place, although I expected that nowhere on the planet would be that barren.

amongst the rocks and sand and not see a single living thing. Not a bug or weed or fly managed to live in such a desiccated place, although I expected that nowhere on the planet would be that barren.

Nearly thirty years ago I took a course in Icelandic literature at the University of Victoria, I was on the other end of that strange ignorance born from a lack of personal experience. I am from eastern Canada, and was lucky enough to grow up in a rural area where I had the four seasons explained to me in terms of the movement of the sun. Victoria has a monsoon climate, which means there are two seasons, summer, in which it rarely rains and is sunny nearly every day, and monsoon winter, in which it rarely is cold enough to snow but rains nearly every day.

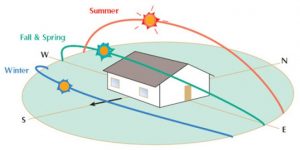

People living in a monsoon climate know little about the movement of the sun in the winter, and that is why, when the question arose in class I had difficulty telling my instructor and fellow students what a line in the text meant. The line from the Vinland Sagas we were studying made reference to the “sun marching around the corner of the house” and the professor confessed that he had never understood the meaning of that line. He knew the line was referring to the passage of time,  but it made no sense to him that the sun’s movement could be used in this context. I tried to explain it from my seat, but when that made no sense to anyone in the class, I was allowed to go to the board and try my hand at drawing the movement of the sun.

but it made no sense to him that the sun’s movement could be used in this context. I tried to explain it from my seat, but when that made no sense to anyone in the class, I was allowed to go to the board and try my hand at drawing the movement of the sun.

In the northern climates, the earth’s tilt along its year-long orbit is angled in such a way that the sun does not climb from the due east and drop in the due west as it does in the tropics, but rather appears to cut across the corner of the sky. At times during the winter, the sun in the very far north merely peeks above the horizon, travels along it briefly, and then dips below again. That means, as far as the view from the ground in a stable place like a house, the summer sun will rise due east, and then as the year grows later it will rise further and further in the south, until the winter solstice passes, and then it will begin its trek back to the location of its summer rising. In other words, to the careful observer, the sun appears to travel around the corner of the house.

like a house, the summer sun will rise due east, and then as the year grows later it will rise further and further in the south, until the winter solstice passes, and then it will begin its trek back to the location of its summer rising. In other words, to the careful observer, the sun appears to travel around the corner of the house.

This halting of the sun’s movement is happening as I write this tonight, for we are partway through the longest night of the year, December 21st. I know, intellectually if not intuitively, that the sun will be a little stronger tomorrow, and will rise slightly higher in the sky each subsequent day until nights of minus seventeen, like now, are a thing of the past.

All those years ago, I stood at the board in that classroom, and even though I did not have the pedagogical tools at my disposal that I have now that I have been teaching for twenty years, I tried my best to explain to them how the sun might appear to travel, at least when it is described poetically. The professor was patient, and tried to understand me, and the students were by turns attentive and dismissive, depending on their temper, but none of them could make out what I was claiming. In fact, and I could see this by their faces, many thought I was spouting pure balderdash.

Finally, the professor feigned to understand, just to get me to return to my seat, and left me to puzzle over why something that should be so simple, something to me that was so obvious, should be so difficult to explain or understand. It was a few days before I realized that I had been lucky to grow up in a rural area where the sun’s rising throughout the year was noticed and remarked upon. I rose early for school, and was able to see the movement of the sun, as day by day, it rose farther and farther to the south before the winter solstice and then farther east  in the spring. Finally in summer, I remember the sun setting in a huge golden ball right in the middle of the north south running road.

in the spring. Finally in summer, I remember the sun setting in a huge golden ball right in the middle of the north south running road.

For those of my fellow students, as well as my professor, who had grown up in Victoria, where the leaden clouds are parted for perhaps three times the entire winter, they would have had no such experience to draw upon. For them, the sun was sighted but rarely and was more or less in the same place in the sky. If I had been their astronomy professor explaining how the tilt of the earth affects the angle and location of the rising sun they would no doubt have made more effort, but since I was merely the student from the back of the class who took it upon himself to interpret a line from the Vinland Sagas, and used such an arcane notion of the movement of the sun, they could not credit it.

I’ve thought since that there was likely no way that I could have described such a difficult matter to people for whom it seemed to be patent nonsense. They had never seen the sun moving around like I described, and had put little thought into what the axial tilt of the Earth might mean. Therefore,  I was explaining something arcane by reference to something impossible. I was like a man explaining how the ghost he had seen was related to religious mythology. My fellow students might have tested my statement by research, but without the visceral experience, they would have difficulty even knowing which thread to follow.

I was explaining something arcane by reference to something impossible. I was like a man explaining how the ghost he had seen was related to religious mythology. My fellow students might have tested my statement by research, but without the visceral experience, they would have difficulty even knowing which thread to follow.

The acknowledgement of geographical limitations on a student’s ability to learn is an important aspect of a general pedagogical approach. Northern lights can be

The aurora of February 9, 2014 seen from Churchill, Manitoba at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. Moonlight lights the landscape. Cassiopeia is at upper left. (Alan Dyer/VWPics/Redux)

described to someone from the topics, but it might be better to use a video, and likewise for the tides to someone from a landlocked country. I have taught texts about the ocean in Winnipeg many times, but each time I make sure to describe what the tides are like on the ocean to the observer on the ground,  and by using the large lakes north of the city, the action of waves. As instructors, we need to ensure that we put some thought into the basis of understanding that our students might have, whether that is due to their cultural background, or the influence of geography.

and by using the large lakes north of the city, the action of waves. As instructors, we need to ensure that we put some thought into the basis of understanding that our students might have, whether that is due to their cultural background, or the influence of geography.