One of the central problems when dealing with a creative writer is that of their emotional  investment in their work. They do not see what they have written as merely product, such as a snail and their shell, but rather can become quite impassioned when criticism is leveled at their baby. Part of this vociferous defensiveness lies in a misunderstanding of what creative work is, and we can blame the English Romantics for this notion of the tormented artist, as well as a general lack of understanding of writing as a craft.

investment in their work. They do not see what they have written as merely product, such as a snail and their shell, but rather can become quite impassioned when criticism is leveled at their baby. Part of this vociferous defensiveness lies in a misunderstanding of what creative work is, and we can blame the English Romantics for this notion of the tormented artist, as well as a general lack of understanding of writing as a craft.

The emotional connection that a writer has to their work is difficult to discuss. Every statement which is not gushing praise reads like a knife to the chest, and every attempt to suggest a modification a hate crime.  They will proclaim, their voice quavering with emotion, “But I poured out my heart on this!” For them this statement should forestall criticism. They have done their best. They have pulled their beating heart from their chest and then squeezed it over the page. What reader could not taste the richness of their blood? Who are you to attempt to correct my emotional state? Who are you to say my story is poorly constructed when it perfectly represents my inner turmoil?

They will proclaim, their voice quavering with emotion, “But I poured out my heart on this!” For them this statement should forestall criticism. They have done their best. They have pulled their beating heart from their chest and then squeezed it over the page. What reader could not taste the richness of their blood? Who are you to attempt to correct my emotional state? Who are you to say my story is poorly constructed when it perfectly represents my inner turmoil?

If we accept their premise, then they are correct to claim that no one should gainsay their efforts. The premise needs to be examined, however, before we can accept it as easily as the writer makes their impassioned  defense. The notion that lies behind their statement “But I poured out my heart on this!” is that their work is an exhibition of the suffering artist’s torment delivered onto paper, at least in the case of the writer. For them, the artist knows instinctually what is required. Their inner turmoil is the pen, the paper, and the hand that writes. The audience should be able to read their words and peer into the maelstrom that is their emotional self.

defense. The notion that lies behind their statement “But I poured out my heart on this!” is that their work is an exhibition of the suffering artist’s torment delivered onto paper, at least in the case of the writer. For them, the artist knows instinctually what is required. Their inner turmoil is the pen, the paper, and the hand that writes. The audience should be able to read their words and peer into the maelstrom that is their emotional self.

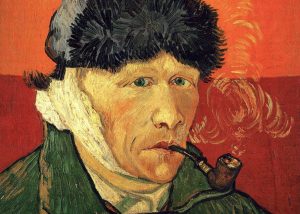

This pernicious notion first enters English letters with the Romantics. William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron,  William Wordsworth, John Keats and company can be seen as using their work to siphon their emotional state onto the page. “The immortal spirit grows like harmony in music” Wordsworth tells us, but such bombast must have some reasoning behind it. Through them—with perhaps the exception of Coleridge and Blake who were very aware of the craft of writing—we inherit an idea of the tortured artist. The emotional state becomes the most important aspect to art and suddenly the notion of gradually refining the craft becomes alien.

William Wordsworth, John Keats and company can be seen as using their work to siphon their emotional state onto the page. “The immortal spirit grows like harmony in music” Wordsworth tells us, but such bombast must have some reasoning behind it. Through them—with perhaps the exception of Coleridge and Blake who were very aware of the craft of writing—we inherit an idea of the tortured artist. The emotional state becomes the most important aspect to art and suddenly the notion of gradually refining the craft becomes alien.

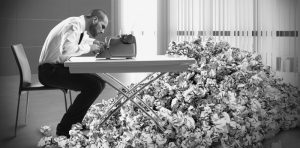

This notion  persists into modern day, and we can hear people talk about suffering from “writer’s block,” losing their inspiration, regurgitating their mental state onto the page, and how the story came to them in a dream in its final form. They speak of writing as if they were talking about channeling spirits, as if their dexterity with language were not responsible when their hands moved across the page. Once we overturn the notion of the muse or divine inspiration, however, writer’s block is not a possibility, except perhaps for those in the late stages of dementia.

persists into modern day, and we can hear people talk about suffering from “writer’s block,” losing their inspiration, regurgitating their mental state onto the page, and how the story came to them in a dream in its final form. They speak of writing as if they were talking about channeling spirits, as if their dexterity with language were not responsible when their hands moved across the page. Once we overturn the notion of the muse or divine inspiration, however, writer’s block is not a possibility, except perhaps for those in the late stages of dementia.

The heart that is to blame for the words on the page is only one aspect of the craft of writing, and that is implicit in their statement about “pouring” out their heart. They are focusing overmuch on the least competent aspect of a writer: their emotional state. In fact, the way in which the heart gets onto the page, the action of pouring, is much more responsible for the final product.

Their emotional reaction to criticism is a reaction to an attack on their personality, but in fact the reader is seldom interested in whatever aspect of the author’s overwrought nature that inspired them to get the words on the page. The reader cares more about the only aspect of the pouring that they have access too, which is the textual artifact. And pouring, like anything we do that affects change in the world around us, is a craft. The reader questioning the choices a writer makes is rarely concerned with their personality.  Instead, they are questioning their ability to pour. The critic is pointing out the shaky hand that spilled wine on the table. They are interested in the writer’s decision to lift the spout until the liquid splashes into the cup, and how they pour too little or too much at a time so that wine either froths or the drinker must wait long moments for their glass to be full.

Instead, they are questioning their ability to pour. The critic is pointing out the shaky hand that spilled wine on the table. They are interested in the writer’s decision to lift the spout until the liquid splashes into the cup, and how they pour too little or too much at a time so that wine either froths or the drinker must wait long moments for their glass to be full.

The focus on the ego of the writer means that they are presuming that the delivery of the heart doesn’t matter, but rather the fact that they have a heart and are talking about it is sufficient. In fact, as most writers know, the craft takes many years to learn and perfect. Some people seem to have more or less gift—just as the contestants on talent shows seem to be great singers at a young age—but behind every public performance are many a thousand hours of practice and gradual perfection of the craft.

When facing criticism, the writer needs to examine their story more carefully. Did they choose its best method of delivery? If they were to change their narrator, would the story evoke their emotional state more accurately, or if they cut the sentences with too many subordinate clauses into several shorter sentences, would the reader feel the implicit speed or would they be distracted by such obvious artifice?

Everyone has a heart they would like to have read by others, but writers are those who can take that emotional content and package it in a way that evokes the feelings they desire in their readers. Learning how to manipulate packaging is a long and tortuous procedure which involves pouring the heart again and again until it has been dumped on the page so many times it appears as a thick puree.  Just as anyone who has learned to pour from a bottle has learned, syrup moves differently than vinegar, and a jug works differently than a pitcher. Each liquid demands its own container and art of pouring, and mere excitement about pouring is not enough to ensure that everyone gets a drink in their glass.

Just as anyone who has learned to pour from a bottle has learned, syrup moves differently than vinegar, and a jug works differently than a pitcher. Each liquid demands its own container and art of pouring, and mere excitement about pouring is not enough to ensure that everyone gets a drink in their glass.