Saltpeter, or nitrate, was a major export of Chile until artificial production began in Germany in the thirties. Then, like much of the world staggering as a result of the global depression, Chile suffered from the loss of nearly fifty percent of its resource exports. The town itself—abandoned  fourteen years after it had been built—was vandalized for decades until Salvador Allende tried to have it restored.

fourteen years after it had been built—was vandalized for decades until Salvador Allende tried to have it restored.

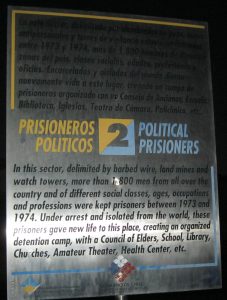

Unfortunately, American tendencies to interfere with successful leftist governments were conspiring against him and Allende was ousted and then executed in favour of the infamous puppet dictator Pinochet. Pinochet used the town as a concentration camp  for political dissidents and intellectuals. Bullet holes in the walls still testify to the people who were killed there, but before long the desert reclaimed the town and now only the ruins remain despite international efforts to maintain the buildings.

for political dissidents and intellectuals. Bullet holes in the walls still testify to the people who were killed there, but before long the desert reclaimed the town and now only the ruins remain despite international efforts to maintain the buildings.

When we visited the town in the South American fall of 2017, raiding parties from the local towns were twisting the knife in the dying corpse of the town. They would come at night, the security guard told us, and bypassing both his dogs and the druglords making deals in the austerity of the desert night, they would tear the ponderosa pine  boards and timbers away from the old buildings. His five dogs exist to fight against this problem, but in the winter of 2018 a dog was killed and the guard himself was shot. Local mafia are rapidly decimating the last of the remaining buildings and soon only the

boards and timbers away from the old buildings. His five dogs exist to fight against this problem, but in the winter of 2018 a dog was killed and the guard himself was shot. Local mafia are rapidly decimating the last of the remaining buildings and soon only the  graveyard—which superstitious South Americans tend to avoid because of a fear of ghosts, although the graves are looted for the bones as well—will suggest that Chacabuco existed at all.

graveyard—which superstitious South Americans tend to avoid because of a fear of ghosts, although the graves are looted for the bones as well—will suggest that Chacabuco existed at all.

It occurred to me, looking at the walled-in nature of the town, and comparing the spacious house for the owner and the cramped cells for the workers, that Chacabuco is merely fulfilling a destiny that was inevitable from its inception. As soon as the autocratic mining town began production, the workers were exploited as much as the land from which the nitrates were unearthed. The town’s association with brutality extended quite naturally into the era of the American puppet Pinochet—despite the best efforts of Allende to preserve Chilean history. Pinochet incarcerated hundreds of political prisoners and many of them did not survive the experience, thus confirming that the town is a place for misery and opportunism.

Given its history, it is perhaps no wonder that the plains that surround the crumbling ruins seethe with druglords and distant gunfire, and that local mafia come to scavenge from the carcass of the remains. In many ways a town that began in brutality and the oppression of its workers still works within the narrow confines of that grim legacy.

no wonder that the plains that surround the crumbling ruins seethe with druglords and distant gunfire, and that local mafia come to scavenge from the carcass of the remains. In many ways a town that began in brutality and the oppression of its workers still works within the narrow confines of that grim legacy.