I have driven across Canada over fifty times, although that measurement is contested by my friend. Everyone gets cranky when they are overtired or have had a bad day, or just when someone is annoying, but when some of my friends get argumentative, odd reasoning comes to the surface.

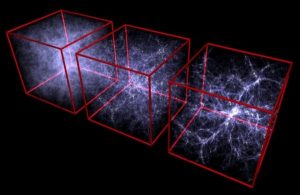

I have dealt with such irritability before, and likely I am guilty of the same unfortunate habit, but I have noticed the tendency to argue about unimportant (at least in terms of our lives) matters has a direct correlation to their temper of the moment. One friend wanted  to have a late night argument about dark energy. I was taking an astronomy course and I exclaiming about the class content and he began to question me. We dug into the ideas a bit and before long it became clear that he wasn’t actually interested in knowing what I’d learned, so much as he wanted to find the thread which could be pulled and unravel the whole theory. I was talking about how the universe was relatively stable when I was a child, and then that was upturned when I learned the galaxies were moving gradually apart. When that was superseded by observations which indicated the galaxies were receding at an ever-increasing speed, our scientific understanding of the universe had to be amended.

to have a late night argument about dark energy. I was taking an astronomy course and I exclaiming about the class content and he began to question me. We dug into the ideas a bit and before long it became clear that he wasn’t actually interested in knowing what I’d learned, so much as he wanted to find the thread which could be pulled and unravel the whole theory. I was talking about how the universe was relatively stable when I was a child, and then that was upturned when I learned the galaxies were moving gradually apart. When that was superseded by observations which indicated the galaxies were receding at an ever-increasing speed, our scientific understanding of the universe had to be amended.

I found that gradual addition to our scientific understanding fascinating, but for my friend, who’d also learned about the static universe when he was young, such capriciousness from the stolid scientific establishment just seemed flaky.

Even though he is not one of those who disbelieve the efficacy of vaccines or denigrate global warming science, in his urgency to prove me wrong—although I was merely poorly reporting what I’d learned and may have had many details incorrect—he used the same argument as those worthies who think the world is flat because they cannot imagine how it could be a globe. “If the scientists can’t figure out what is going on—if they keep changing their mind—why should we listen to them.” The other part of the argument was equally emotive. He argued that the way he’d first learned about the universe was somehow more accurate because he’d encountered that earlier.

My friend is far from a conspiracy theorist or even an anti-intellectual anti-science person. In fact, he demands proof for the work that he is engaged in and would dislike such arguments himself. That he became subject to them was more of a product of a late night and his crankiness than anything else. Once I realized that, I told him to call my professor if he was that interested. I wasn’t a good source, for my  understanding of physics is that of a layperson rather than a serious scholar. Or as people say online, Google is your friend.

understanding of physics is that of a layperson rather than a serious scholar. Or as people say online, Google is your friend.

Another friend reacted similarly when he wanted me to explain how a non-literate culture is just as advanced as a literate one. He was rationalizing the so-called civilizing process of Christianising. He is in favour of missionary work, like many Christians, and when I said those cultures they were attempting to displace were valuable in  their own right he objected. The tribes living in the forest are happy to have someone come with new gods, he claimed. And, as far as he was concerned, anyone who lives in a mud hut and cannot read does not have a culture worth saving. I tried talking about the different ways that culture knowledge have been transmitted, but his science background and religious upbringing didn’t allow him to see the value in such notions.

their own right he objected. The tribes living in the forest are happy to have someone come with new gods, he claimed. And, as far as he was concerned, anyone who lives in a mud hut and cannot read does not have a culture worth saving. I tried talking about the different ways that culture knowledge have been transmitted, but his science background and religious upbringing didn’t allow him to see the value in such notions.

When he began to argue—while in the same type of mood—that I couldn’t possibly have travelled across Canada as many times as I’d claimed, then his argument grew more convoluted. The math became reliant on a semantic notion of what a trip across Canada is, and how that might compare to the many trips I had made. He knew I’d lived in both western and eastern Canada, and now in the centre, and that I was accustomed to travelling back and forth every year, at least for a decade or so, but he didn’t feel that was represented properly when I claimed to have driven across the country so many times.

He said that a trip from eastern Canada to the west was not a single trip, but rather half a trip. “Surely,” he scoffed, “you would be coming back. The only way it’s a trip across the country is if you make a round trip. That is a single trip across the country.”

I was as curious about this attempt to reason away his crankiness as I was the notion that science should be still, or his earlier statements that non-literate culture were not true cultures. Still trying to wrap my head around the way of thinking, I asked him, “So a trip from eastern Canada to the west is not a trip across the country for you?”

“No. because it is only half the trip. If you come back, then that’s a trip across Canada.”

“That will be disappointing for all those who move to western Canada. They will feel like they are crossing the country, and they will physically be crossing the country, going across the entire breadth of the country, travelling as many kilometres as it is across the country, but they will be wrong. If they never move back to the east, then they will leave half a trip hanging. They will never have actually crossed the country.”

He dug his heels in at that point and repeated his argument.

“So the trips I have done across Canada, you would say are only half a trip. So that means if I drove halfway across Canada, then it’s actually a quarter trip? That if you drove to the city (which was about sixty kilometres away) that you never actually drove to the city. You only drove halfway, because you have yet to drive back. In fact,” the implications of the notion were fascinatingly nonsensical—“if you only went halfway to town, or what you would call a quarter of the way, then drove back, you would only have driven halfway on your trip, even though you would have driven the equivalent of the entire distance.”

When the argument continued, which is one of the problems of both of us engaging when we’re talking nonsense, I gave him another example. He is far better at math than me, but I felt the equation was simple enough that I could handle it. “So the distance across Canada is five thousand kilometres. That’s what most people would claim.” He agreed to that premise. “So if I drove five thousand kilometres  across the country, you would instead say that that wasn’t across, but rather halfway. Somehow the five thousand kilometres would be converted in your mind to two thousand five hundred, and all of those suckers who think they are driving five thousand—and their gas mileage and odometer readings would confirm the five thousand—they would be tricked?”

across the country, you would instead say that that wasn’t across, but rather halfway. Somehow the five thousand kilometres would be converted in your mind to two thousand five hundred, and all of those suckers who think they are driving five thousand—and their gas mileage and odometer readings would confirm the five thousand—they would be tricked?”

I don’t think he appreciated the math as much as I did, and the argument trickled off into a change of topic. The notion has remained with me however. I read the situation as a caution to us all, for we get just as irritable as a child who won’t go to sleep when it’s bedtime, and we need to watch ourselves for nonsense. As well, when we find someone making such illogical claims, then we might need to treat them as someone who cannot handle the social situation they are in. in that moment it might be better to say, Google is your friend.

Not many years ago, search engines did not exist, and information was much harder to locate. Many arguments in bars or over late night dinner parties almost came to blows. Now we may merely point our interlocutor to their handheld. Many a conversation that seemed so important just a few decades ago, has now disappeared into the smoke of ignorance dissolved when a search is so easy to do, and now someone who wants to argue about statements of fact is willfully causing trouble.