The first time I encountered the notion of retirement and pensions was nearly twenty years ago when I was working at Worcester State College. I had  just been hired, and although they only intended to give me full time hours for a term—which was only because they were in a bind and needed more people with PhDs—I was invited to a meeting about health care and paperwork. I learned two things about working there at the meeting. I didn’t really fit in, and

just been hired, and although they only intended to give me full time hours for a term—which was only because they were in a bind and needed more people with PhDs—I was invited to a meeting about health care and paperwork. I learned two things about working there at the meeting. I didn’t really fit in, and  the arcane and confusing type of work-sponsored private healthcare on offer was worse than just getting sick.

the arcane and confusing type of work-sponsored private healthcare on offer was worse than just getting sick.

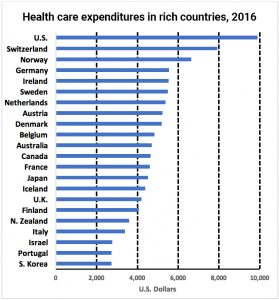

My difference in attitude became obvious in the discussion of health care, for, being from Canada, that was the first time I’d encountered the complacency the culture had about paying a private company to pay another system to provide a service.  That has become more ubiquitous in more recent years, such as paying a private service to order and deliver a meal from a restaurant around the corner. While at one time we would call the restaurant directly, we now engage a third party, and pay them for the service instead of having the food delivered cheaper and quicker.

That has become more ubiquitous in more recent years, such as paying a private service to order and deliver a meal from a restaurant around the corner. While at one time we would call the restaurant directly, we now engage a third party, and pay them for the service instead of having the food delivered cheaper and quicker.

I was always struck by the American antipathy to paying taxes. They didn’t trust the government with their tax money, and instead would rather give their money to a for-profit private corporation. Even though the stated aim of the private company was keeping money for themselves, my American neighbours would still rather give them the cash than trust a government which they voted in and which ostensibly was responsible to them.

The impact and folly of that way of thinking was clearest to me when I was sitting at a  toll booth. I sometimes waited twenty minutes, and everyone around me was doing the same. With our engines running we would creep ahead a few metres at a time, in order to pay a man in a booth fifty cents for the kilometres (or miles) we had driven. All of this, I thought at the time, just so you don’t have to pay taxes to the department of transport. They were so afraid of government mismanagement they would rather take hours out of their working life sitting in traffic. They wanted to make sure that fifty cents went to the corporation which could be trusted to pocket as much of it as they could.

toll booth. I sometimes waited twenty minutes, and everyone around me was doing the same. With our engines running we would creep ahead a few metres at a time, in order to pay a man in a booth fifty cents for the kilometres (or miles) we had driven. All of this, I thought at the time, just so you don’t have to pay taxes to the department of transport. They were so afraid of government mismanagement they would rather take hours out of their working life sitting in traffic. They wanted to make sure that fifty cents went to the corporation which could be trusted to pocket as much of it as they could.

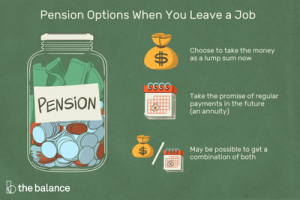

The other aspect of the meeting which has remained with me was the discussion of retirement. I was in my thirties, and ostensibly beginning a professional job, so the talk of pensions made sense, but I felt like I was too young to worry about such things. I was only planning to work for a few years after the PhD so I could then take time off and travel. When they announced the next topic of conversation as pension plans,  I glanced around me with a grin, expecting the others to share my reaction. Instead, my colleagues nodded and looked seriously through the paperwork, debating which 401(k) might best suit their needs even while they contemplated the delight of never having to work again. I didn’t trust that a job in my field would last any length of time, so I didn’t feel like the session affected my life, so I leaned back to watch as others filled out forms and debated returns.

I glanced around me with a grin, expecting the others to share my reaction. Instead, my colleagues nodded and looked seriously through the paperwork, debating which 401(k) might best suit their needs even while they contemplated the delight of never having to work again. I didn’t trust that a job in my field would last any length of time, so I didn’t feel like the session affected my life, so I leaned back to watch as others filled out forms and debated returns.

I am older now, and I no longer view the notion of retirement with the same cavalier air. My job security hasn’t essentially changed from when I first started work, for the only thing which could make my employers uncomfortable quicker than the notion of offering a permanent position is the idea that employees might have benefits. I am, of course, somewhat at fault. I chose the field of English literature which both graduates many candidates every year, is fundamentally nepotistic in how hiring is done, and which universities increasingly devalue. My friend said recently that her bosses have no idea what her job entails; that is also true of English literature. If anyone thinks about the profession at all, they imagine glorified grammar teachers, overly persnickety about the finer points of punctuation even while they struggle to open a ziplock bag.

The paucity of positions aside, especially if one is unable to unwilling—in my case—to live in places humans have long since abandoned as unfeasible, I have also never been offered a pension plan since that early September after the turn of the millennium. Now that I reflect on other professions, where my friends have been paying into pension plans—and even more lucratively, have had their employers match that—I realize they are looking into a much earlier and more positive retirement than I can imagine.

Many of those people are contemplating  whether they should take early retirement—at fifty-five—or wait for a more generous package at sixty. In my case, I have no such pension options. The money I have is only that which I have saved, and way of thinking about and my access to retirement is relatively unchanged. Now, instead of viewing the notion with the humour of youth, I see a closed door and a burned out lightbulb in the hall.

whether they should take early retirement—at fifty-five—or wait for a more generous package at sixty. In my case, I have no such pension options. The money I have is only that which I have saved, and way of thinking about and my access to retirement is relatively unchanged. Now, instead of viewing the notion with the humour of youth, I see a closed door and a burned out lightbulb in the hall.

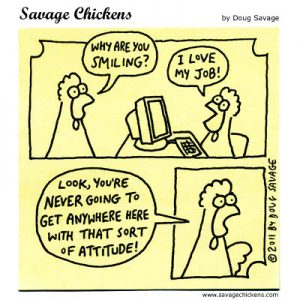

This came up again recently with my friend who works for the municipal government. She is imagining the delights of early retirement, and counting down the days until that glorious moment becomes possible. Although I am now fifty-six, I cannot imagine retiring just yet, so I asked her if she hated her job. No, she told me. She likes what she does, but she just wants more time to pursue her own interests.

Although she tells me she  likes her job, the way it interferes with her life makes it sound as though it is not as enjoyable as she pretends. Instead the job is an impediment to her life. She has plans which the job will not allow, such as setting up a garden. For some reason, she has put those schemes on hold and waited until retirement to pursue them. A man in his sixties told me when I was yet a teenager that I should copy him. “Get a good job, and then save until you retire. Then you can do whatever you want.”

likes her job, the way it interferes with her life makes it sound as though it is not as enjoyable as she pretends. Instead the job is an impediment to her life. She has plans which the job will not allow, such as setting up a garden. For some reason, she has put those schemes on hold and waited until retirement to pursue them. A man in his sixties told me when I was yet a teenager that I should copy him. “Get a good job, and then save until you retire. Then you can do whatever you want.”

At the time I was horrified by the proposal. I was only sixteen, so I couldn’t imagine waiting all those years to live my life. I tried to picture his life, as he’d fed the  chickens in the factory farm, waiting every day to buy the RV and go to Arizona in the winter. I determined that would not be me. I never imagined that I would get a job that I liked, since so much of the work I did at the time was drudgery, but I knew that I wouldn’t put my life on the shelf to be taken down only when I needed help with steps and ladders.

chickens in the factory farm, waiting every day to buy the RV and go to Arizona in the winter. I determined that would not be me. I never imagined that I would get a job that I liked, since so much of the work I did at the time was drudgery, but I knew that I wouldn’t put my life on the shelf to be taken down only when I needed help with steps and ladders.

To my surprise, I ended up enjoying my work. I think that the work I do is important, and makes a contribution to my community, even though it is not considered valuable by the more pecuniary culture we have built. I would sometimes tell my students that the true measurement of whether you like your job is whether you would do it for free. Although I would want a thousand an hour for marking, I would teach for free—which is just as well since I am paid near starvation wages for the privilege. Like many people teaching on university contracts, I cobble together courses from more than one workplace and make it work. That means that without the high wages and free time of my colleagues, I have to think harder about my spending in order to save for my retirement, and that without job security, I am constantly on the edge of being unemployed.

I would teach for free—which is just as well since I am paid near starvation wages for the privilege. Like many people teaching on university contracts, I cobble together courses from more than one workplace and make it work. That means that without the high wages and free time of my colleagues, I have to think harder about my spending in order to save for my retirement, and that without job security, I am constantly on the edge of being unemployed.

In former years, I have viewed that as an advantage. Few people with a PhD would work for starvation wages (in fact, many that I went through graduate school with have left the field), so the market was not nearly as saturated as it is today that more people are thirsty. That meant I could take time off to pursue my own interests and perhaps be able to find work when I returned. I took a three week canoe trip down five hundred kilometres of river, built a wooden sailboat and plied the inner passage off Vancouver, BC, made a dozen trips overseas to Asia and South America, and built a cabin in the woods. I built the garden that my friend doesn’t have time for this summer when I was confined like many others in the various lockdowns, and built and modified furniture. I drove across Canada over fifty times, and explored remote logging roads and found hidden beaches in Alberta, British Columbia, and the Yukon. Amongst those projects, I have written fifty-six books, on topics ranging from academic works to autobiography, travelogues to poetry, and novels to short story collections.

Now that retirement is looming for my friends, and I hear them talking about what they will do with their time once they no longer are selling it for a sinecure, I hear the sixty-year-old chicken farmer. I have not completely been the grasshopper in the Ant and the Grasshopper story, for I have also saved money. I may not have as much income when I finally decide I’ve either had enough of my job or I cannot work any longer because I have been fired or become incompetent, but in the meantime I have turned my mind to every project which drew my attention, and never skimped on my life in favour of a future few people live to enjoy.

I finally decide I’ve either had enough of my job or I cannot work any longer because I have been fired or become incompetent, but in the meantime I have turned my mind to every project which drew my attention, and never skimped on my life in favour of a future few people live to enjoy.