Many older people often fall into the trap of believing or pretending that the world was better  when they were young. They mistakenly presume that their nostalgia means that their memories are worth more than those who are young now, despite the fact that the younger people are creating their own nostalgic glimpses for later perusal. For example, nearly every page online that allows comments feature someone complaining that the world is not as good as when they were young. They are frequently answered with accurate statements about their boomer status, or quips making fun of the old man threatening the children stepping on his lawn.

when they were young. They mistakenly presume that their nostalgia means that their memories are worth more than those who are young now, despite the fact that the younger people are creating their own nostalgic glimpses for later perusal. For example, nearly every page online that allows comments feature someone complaining that the world is not as good as when they were young. They are frequently answered with accurate statements about their boomer status, or quips making fun of the old man threatening the children stepping on his lawn.

My story is not meant to bemoan the complexity of modern cars—and at twenty-three years old, my current Civic can scarcely be called new—but rather to explore how certain verities haven’t changed. For instance, the mechanics of yesteryear were no more aware of how to fix my Honda than they are today, and my best tool was persistence, constant observation, and a kind of meditative resignation to my fate.

My 81 Civic was much  easier to work on than modern cars, for it was missing many of the electronics that they are burdened with. Those electronics, the various sensors and solenoids, as well as the ECU, the Engine Control Unit make some tests impossible for the backyard tinkerer, and in other cases merely shut the car down without any information about what may have happened to cause the error. They have their uses, for instance the gas mileage on many modern cars is owed to the electronics monitoring the car’s combustion and power levels. My old civic was much more forthcoming. If I had spark, I knew to blame the problem on fuel delivery or the carburetor.

easier to work on than modern cars, for it was missing many of the electronics that they are burdened with. Those electronics, the various sensors and solenoids, as well as the ECU, the Engine Control Unit make some tests impossible for the backyard tinkerer, and in other cases merely shut the car down without any information about what may have happened to cause the error. They have their uses, for instance the gas mileage on many modern cars is owed to the electronics monitoring the car’s combustion and power levels. My old civic was much more forthcoming. If I had spark, I knew to blame the problem on fuel delivery or the carburetor.

The carburetor in that car was already becoming complex, however, for it had three fuel passages, corresponding to the idle circuit, the full throttle open mouth, and some other function I never understood completely. That meant it was complex enough that when I had problems with it I contemplated taking it to the professionals. I stopped at a Honda dealership garage and talked with a mechanic—that’s more difficult to do now as well—and the mechanic told me doubtfully that the carburetors were complex enough that even if they

corresponding to the idle circuit, the full throttle open mouth, and some other function I never understood completely. That meant it was complex enough that when I had problems with it I contemplated taking it to the professionals. I stopped at a Honda dealership garage and talked with a mechanic—that’s more difficult to do now as well—and the mechanic told me doubtfully that the carburetors were complex enough that even if they installed a carb kit they wouldn’t guarantee the work. I was having intermittent fuel mix problems, which meant that I occasionally had to run with the manual choke on while idling, and turn it off when driving on the highway. It would be confusing for anyone trying to steal the car—a kind of early generation immobilizer—but I doubt that was the point.

installed a carb kit they wouldn’t guarantee the work. I was having intermittent fuel mix problems, which meant that I occasionally had to run with the manual choke on while idling, and turn it off when driving on the highway. It would be confusing for anyone trying to steal the car—a kind of early generation immobilizer—but I doubt that was the point.

I struggled with the problem for a few years, but in the meantime another problem appeared. I would be driving in cooler temperatures and the car would die on the side of the road. If I waited a few minutes, it would start again and run well for another twenty minutes or so. Looking for the source of the problem, I found that a kind of viscous substance coating the main jet in the carburetor when I took off the air filter cover. It would disappear even while I looked at it, and when it was gone the car ran fine.

On one occasion I was driving on the highway and managed to get off the ramp before the car died. My friend Darryl and I walked to a nearby gas station,  for I was starting to imagine water in the gas and that methyl-hydrate in the gas tank might solve the problem. If nothing else, then the walk meant the car had time to evaporate the viscous coating. While we were buying methyl-hydrate a local tow truck driver offered us a ride back to the car. We took the ride, and once we arrived he snapped into sales mode. He pulled the cable from the distributor and told me to turn it over. Annoyed, I did what he asked, and then he said the electrical system was shot and that he could tow us.

for I was starting to imagine water in the gas and that methyl-hydrate in the gas tank might solve the problem. If nothing else, then the walk meant the car had time to evaporate the viscous coating. While we were buying methyl-hydrate a local tow truck driver offered us a ride back to the car. We took the ride, and once we arrived he snapped into sales mode. He pulled the cable from the distributor and told me to turn it over. Annoyed, I did what he asked, and then he said the electrical system was shot and that he could tow us.

I’d had enough by that point, so I gestured to Darryl to get in the passenger seat. I reattached the cable, and even while the tow truck driver told me the car was dead, I slammed the hood and got inside. Darryl was concerned. His first southern-Ontario instinct was to trust the authorities,  and he’d suggested that we should call CAA. I told him if your car dies on the side of the road you have to fix it. If you can’t fix it, you sleep in it until you can. As far as he could tell, I was just being stubborn. For my own part, I watched the way the driver held the cable as I cranked over the engine. He wasn’t attempting to get a spark. He was merely playing games to drum up business.

and he’d suggested that we should call CAA. I told him if your car dies on the side of the road you have to fix it. If you can’t fix it, you sleep in it until you can. As far as he could tell, I was just being stubborn. For my own part, I watched the way the driver held the cable as I cranked over the engine. He wasn’t attempting to get a spark. He was merely playing games to drum up business.

I started the car, and then remarked to the man that the electrical system had repaired itself and before long we were on the highway. Of course, none of these shenanigans solved the problem. As the winter grew colder, the problem occurred more often, and I grew to realize that it was more related to temperature than any other variable. This was the time that I began to consult Thirasak Rirksomboon, my Thai friend who was completing his PhD  in chemical engineering. He was more than regularly brilliant, and in one discussion he asked me about the gas tank. I told him how I had repaired it with gas tank epoxy—a quick fix meant to get the user to the garage—and then covered that with tiger hair, fibreglass epoxy. He pulled down a book from the shelf and then suggested that the vaporization temperature of the gas had likely changed because I’d introduced long strand hydrocarbons into it. The gas tank epoxy was breaking down, and the fibreglass and epoxy mix was combining with the gasoline.

in chemical engineering. He was more than regularly brilliant, and in one discussion he asked me about the gas tank. I told him how I had repaired it with gas tank epoxy—a quick fix meant to get the user to the garage—and then covered that with tiger hair, fibreglass epoxy. He pulled down a book from the shelf and then suggested that the vaporization temperature of the gas had likely changed because I’d introduced long strand hydrocarbons into it. The gas tank epoxy was breaking down, and the fibreglass and epoxy mix was combining with the gasoline.

Once he told me the problem, I not only learned a lot of respect for theoretical knowledge,  but I knew how to fix it. I merely closed off the air intake with a plastic bag, which forced the engine to use the quick warmup pipes. That meant I was raising the temperature of the air, and compensating for the winter air I’d been drawing in cold, and the changing the way the gas vaporized. The problem was solved.

but I knew how to fix it. I merely closed off the air intake with a plastic bag, which forced the engine to use the quick warmup pipes. That meant I was raising the temperature of the air, and compensating for the winter air I’d been drawing in cold, and the changing the way the gas vaporized. The problem was solved.

The other issue was more difficult to sort out. I remembered that the dealership garage wouldn’t guarantee their work, the carburetor was so complex, but I  resolved that I would take it apart myself and keep track of the springs and valves I removed. I opened it up on the car, cleaned out the float bowl, removed and cleaned the tiny mesh screens on their plastic framework, and then put it back together. That worked for a while, and then I did it over when the problem arose again.

resolved that I would take it apart myself and keep track of the springs and valves I removed. I opened it up on the car, cleaned out the float bowl, removed and cleaned the tiny mesh screens on their plastic framework, and then put it back together. That worked for a while, and then I did it over when the problem arose again.

I began to watch my car more closely on my cross-country trips and finally realized that the  problem would appear after the car had overheated. I managed to compensate for the deterioration of my radiator fins by adding a sub radiator using a heater block from a 1940s panel truck and then running with the heater on all the time. Nonetheless, on high mountain roads or in heavy traffic, the car would occasionally

problem would appear after the car had overheated. I managed to compensate for the deterioration of my radiator fins by adding a sub radiator using a heater block from a 1940s panel truck and then running with the heater on all the time. Nonetheless, on high mountain roads or in heavy traffic, the car would occasionally  overheat and the problem would resurface. I cleaned the carburetor a few times more before I realized that the gas filter I had was ineffective, and therefore tiny pieces of rust from the old gas tank was entering the system. The little screens kept them from getting into the jets normally, but when the engine overheated, the carburetor got too hot, and the plastic—which wasn’t made to handle those temperatures and was original to the car—would warp and let dirt into the tiny jets.

overheat and the problem would resurface. I cleaned the carburetor a few times more before I realized that the gas filter I had was ineffective, and therefore tiny pieces of rust from the old gas tank was entering the system. The little screens kept them from getting into the jets normally, but when the engine overheated, the carburetor got too hot, and the plastic—which wasn’t made to handle those temperatures and was original to the car—would warp and let dirt into the tiny jets.

Because it was a carbureted car it wouldn’t die completely, and in fact I believe it ran lean all the time for it got much better gas mileage than it should have—just over fifty miles for the Canadian gallon, 5.4 liters per 100 kilometres, or forty-four miles to the American gallon. With my augmented cooling plant, the car never ran too hot, and it wasn’t lean enough to damage the engine. It might have merely been an underpowered car driven sensibly, for that  could also explain the gas mileage. I installed a new gas filter, cleaned out the carburetor and the problem disappeared. Soon I was worrying about the rear swing arm coming detached from the frame, and despite my and Randy’s attempt to weld it back into place, the car’s days were numbered.

could also explain the gas mileage. I installed a new gas filter, cleaned out the carburetor and the problem disappeared. Soon I was worrying about the rear swing arm coming detached from the frame, and despite my and Randy’s attempt to weld it back into place, the car’s days were numbered.

I drove a few other rusty  Hondas before I bought my 99 Civic for eleven hundred dollars in Toronto. It was a high mileage car, at three hundred thousand kilometres, but the body was in excellent condition. I began to undercoat it every summer, despite not driving it in the winter and keeping it in a garage for most of the year. It came with a check engine light which I was told indicated a problem

Hondas before I bought my 99 Civic for eleven hundred dollars in Toronto. It was a high mileage car, at three hundred thousand kilometres, but the body was in excellent condition. I began to undercoat it every summer, despite not driving it in the winter and keeping it in a garage for most of the year. It came with a check engine light which I was told indicated a problem  with the O2 sensor, but I was able to ignore it. The gas mileage wasn’t as good as my 81 Civic, but at forty-five miles per gallon, it was fine. There were a few problems associated with older cars, like when the brake lines began to burst and I had my mechanic friend replace them. He didn’t do a very good job, and merely hung then beneath the car on zip ties, but at least they work. It was another lesson to not be so lazy and do the work myself. Likewise, the muffler fell apart, the radiator fan and front caliper seized up, and the distributor died.

with the O2 sensor, but I was able to ignore it. The gas mileage wasn’t as good as my 81 Civic, but at forty-five miles per gallon, it was fine. There were a few problems associated with older cars, like when the brake lines began to burst and I had my mechanic friend replace them. He didn’t do a very good job, and merely hung then beneath the car on zip ties, but at least they work. It was another lesson to not be so lazy and do the work myself. Likewise, the muffler fell apart, the radiator fan and front caliper seized up, and the distributor died.

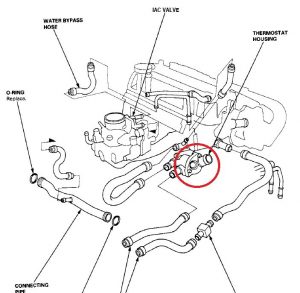

In the case of the distributor, I wasn’t sure what the problem was, and I had the car towed  to a garage when it wouldn’t run long enough to move in the back alley. They replaced the distributor, and I asked them to deal with the rough idling problem I’d had for a few years. I’d tried replacing the throttle body with a used one, and that fixed it for a while. Then I tried replacing the idle control valve, but still I had to either put up with the car switching to rough driving when I didn’t rev the motor sitting at a light, or try to keep it from switching by riding the gas pedal. They gave me a story about it being due to the throttle body gasket, but my four dollar fix didn’t change anything. Like the mechanic from the dealer years before, they didn’t know, and weren’t inclined to tell me that. Instead, they made up a solution.

to a garage when it wouldn’t run long enough to move in the back alley. They replaced the distributor, and I asked them to deal with the rough idling problem I’d had for a few years. I’d tried replacing the throttle body with a used one, and that fixed it for a while. Then I tried replacing the idle control valve, but still I had to either put up with the car switching to rough driving when I didn’t rev the motor sitting at a light, or try to keep it from switching by riding the gas pedal. They gave me a story about it being due to the throttle body gasket, but my four dollar fix didn’t change anything. Like the mechanic from the dealer years before, they didn’t know, and weren’t inclined to tell me that. Instead, they made up a solution.

I continued to tinker  with the idle system, cleaning the old throttle body and reinstalling the idle control valve, but finally I resolved to live with the problem. That’s when a new problem began to surface. While I was driving on the street in Winnipeg, I felt the car suddenly run differently. It had less power, and ran rougher. The problem didn’t go away, and when I drove to eastern Canada with that problem—having the alternator die along the way—I found my gas mileage had tanked. I was getting closer to thirty miles to the gallon instead of the forty-five I’d been accustomed to. I used my mechanic friend’s reader, found out that the crankshaft position sensor had died, and once I was home I began the lengthy procedure of replacing it. Unfortunately, it was likely fine, for its replacement threw the same code. I began to check wiring, and found that although one of the wires was supposed to

with the idle system, cleaning the old throttle body and reinstalling the idle control valve, but finally I resolved to live with the problem. That’s when a new problem began to surface. While I was driving on the street in Winnipeg, I felt the car suddenly run differently. It had less power, and ran rougher. The problem didn’t go away, and when I drove to eastern Canada with that problem—having the alternator die along the way—I found my gas mileage had tanked. I was getting closer to thirty miles to the gallon instead of the forty-five I’d been accustomed to. I used my mechanic friend’s reader, found out that the crankshaft position sensor had died, and once I was home I began the lengthy procedure of replacing it. Unfortunately, it was likely fine, for its replacement threw the same code. I began to check wiring, and found that although one of the wires was supposed to  deliver twelve volts, it did not. I was just getting accustomed to the issue, when I was in eastern Canada and decided it was a significant enough problem—especially given the drastic increase in gas prices—that I would take the car to an electrical shop.

deliver twelve volts, it did not. I was just getting accustomed to the issue, when I was in eastern Canada and decided it was a significant enough problem—especially given the drastic increase in gas prices—that I would take the car to an electrical shop.

I tried out a venerable business, Craig’s Auto Clinic, in Fredericton, because they specialized in electrical work. The results were disappointing, however. Like the problem I had with the rough idle and engine surging, they charged me one-and-a-half hours, one-hundred-and-seventy dollars, and told me the wiring was fine but  the computer was the problem. Perhaps the out-of-province plates proved to be too much of a temptation. Whatever the cause of their chicanery, there were a few red flags. They didn’t call me after the work was done, and when I called they claimed it was two hours work. When I was charged for one and a half hours, I didn’t argue, but I wondered that checking three wires leading from the sensor should be so difficult.

the computer was the problem. Perhaps the out-of-province plates proved to be too much of a temptation. Whatever the cause of their chicanery, there were a few red flags. They didn’t call me after the work was done, and when I called they claimed it was two hours work. When I was charged for one and a half hours, I didn’t argue, but I wondered that checking three wires leading from the sensor should be so difficult.

I took them at their word, and bought a used computer from a nearby junkyard once I was home. Upon installing it, it proved to fix the rough idle issue the car had experienced since I’d owned it, but did nothing for the crankshaft position sensor. It was a minor victory, at best. I traced the wires myself, taking twenty minutes or so, and found out the two signal wires went to the computer without showing faults. The twelve volt line, which I had been hoping the auto electrical people would have fixed, still had no power. I ran a wire from the battery to the sensor on that line to see if I could get the  sensor to register, but with no luck, I’d tried my last experiment. I put everything back together, kept the new ECU in the car, and turned my attention to the O2 sensor. It was throwing a code for an O2 sensor heater, and I’d been reading that might explain my poor gas mileage.

sensor to register, but with no luck, I’d tried my last experiment. I put everything back together, kept the new ECU in the car, and turned my attention to the O2 sensor. It was throwing a code for an O2 sensor heater, and I’d been reading that might explain my poor gas mileage.

I managed to get the old sensor out, and replaced it with a Denso which I’d been reading about online. The O2 sensor error went away, and the car seemed to run better, but I was faced with a decision about how to handle a car that no one seemed able to fix. My friend Tara had a quick fix. She proposed that I buy a Honda Fit, a model I had considered before. At six thousand dollars for a fifteen year old Fit, that notion is less attractive than it first seems. For one thing, all older cars come with problems, and in my case, the Civic at least always started and ran well. I thought back over my gas mileage, which was poor, but not strikingly bad compared to many of the SUVs on the road. My total mileage for a year is well under ten thousand kilometres, which means that I would have to spend around four to five hundred dollars extra for the poor mileage.

seemed to run better, but I was faced with a decision about how to handle a car that no one seemed able to fix. My friend Tara had a quick fix. She proposed that I buy a Honda Fit, a model I had considered before. At six thousand dollars for a fifteen year old Fit, that notion is less attractive than it first seems. For one thing, all older cars come with problems, and in my case, the Civic at least always started and ran well. I thought back over my gas mileage, which was poor, but not strikingly bad compared to many of the SUVs on the road. My total mileage for a year is well under ten thousand kilometres, which means that I would have to spend around four to five hundred dollars extra for the poor mileage.  Even if I didn’t fix the issue with the new O2 sensor, it wasn’t financially feasible to take the car to yet another garage to have them guess and be wrong. Nor did it make sense to buy another high-mileage Honda with another set of problems for six thousand. Such an expenditure would buy lots of gas for my current car.

Even if I didn’t fix the issue with the new O2 sensor, it wasn’t financially feasible to take the car to yet another garage to have them guess and be wrong. Nor did it make sense to buy another high-mileage Honda with another set of problems for six thousand. Such an expenditure would buy lots of gas for my current car.

In the end, the question is one of pragmatism. I decided I was worrying overmuch about the car’s problem with the crankshaft position sensor. That if an official garage couldn’t figure out what it was that I couldn’t be blamed for my similar failures. As well, I decided, if my twenty-three year old car died on the side of the road I wouldn’t be overly worked up, while a newer Fit would annoy me if it did the same. I decided I would live with the problem until it either cleared up on its own—unlikely, although my 81 Civic seemed to fix itself several times—or the car died of something far more fatal. Some aspects in our lives are just not worth the mental energy we put into them, and I had finally decided my car’s issues fit that category.