Many television shows were

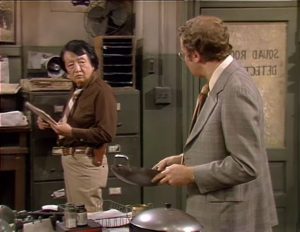

The cast of “Barney Miller” in September 1976: Ron Glass, Max Gail, Hal Linden, Abe Vigoda, Jack Soo.

renowned for their dialogue, and in that way Barney Miller is no different. The show’s portrayal of New York policing, with its kinder and gentler approach to dealing with perpetrators and victims, as well as its ground-breaking inclusion of gay people and people with disabilities, is in other ways remarkable. Although much of its dialogue is focused on or aimed toward the punch line, the sarcastic aside to whatever is happening in the 12th precinct, I was particularly struck by one early interaction between Dietrich and Yemana.

Dietrich is relatively new to the precinct and still learning his place when he makes a casual comment about a wok which has come in as evidence. Thus ensues a kind of wild and confusing ride through what is implied by the interaction rather than what is actually said.

Dietrich: Funny pot

Yemana: It’s called a wok. It’s used to cook Chinese vegetables

Dietrich: Oh, no offense.

Yemana: I’m not Chinese.

Dietrich: Well you were once, round about 4th-5th century.

Yemana: I’ll be 46 in April.

Dietrich: If I don’t see you, happy birthday.

Although Dietrich is normally portrayed as in command of an encyclopedic knowledge about everything, in this moment he worries that his idle comment about the  wok will be construed as racist. It could be read as casual ignorance, but he is concerned that his statement about the cooking utensils from another culture as “funny,” merely highlights its lack of place in dominant culture.

wok will be construed as racist. It could be read as casual ignorance, but he is concerned that his statement about the cooking utensils from another culture as “funny,” merely highlights its lack of place in dominant culture.

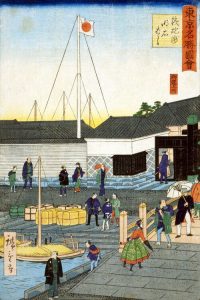

Yemana replies to the lack of knowledge rather than the implied racially-charged slight. He names the wok and identifies its cultural provenance. This encourages Dietrich to read another implication into Yemana’s defense. The implication is that no one would be able to identify the wok, or take it upon themselves to defend the implied slight unless they were also Chinese. This is a running gag on Barney Miller. People are always mistaking American born Yemana for a Chinese man, and he is constantly correcting them.

Yemana then responds to what is implied rather than what was said. “No offense” implies that Dietrich, just like other characters on the show, thinks Yemana is Chinese. Yemana’s answer inspires Dietrich to defend his misinterpretation. As well, he answers in a way that connotes his inability to admit he is wrong. He then uses his encyclopedic knowledge to recall ancient Chinese Japanese trade relationships, as a way of shoring up his claim that his mistake, that although Yemana considers himself to be Japanese, he is Chinese actually, kind of, or once was.

be Japanese, he is Chinese actually, kind of, or once was.

Yemana hears the subtext. An argument from ancient history does not sway him to believe that he is Chinese. He wants to say that was a long time ago, that such concerns of the Chinese and Japanese people from five centuries earlier have nothing to do with him as an American Japanese man. So he answers with his age. That is his way of saying what happened all that time ago has nothing to do with him.

Dietrich shifts his strategy. Now he is no longer going to address the implications of his statements, but rather refuse to acknowledge the implication that Yemana is too young to have anything to do with cultural trade five centuries earlier. Since the birthday Yemana refers to is not immediate, his offer of a birth greeting is stilted. The moment of dialogue wraps up with a pre-emptive happy birthday, leaving both Yemana and Dietrich confused as they walk away from the conversational minefield.

Such missteps in human interactions are not so unusual that we cannot recognize the awkwardness of the encounter. But it’s worth noting that this piece of dialogue was written for its comedic value. The writing staff deliberately put together a series of utterances which each miss their mark in terms of what the characters want to say. That is where the humour lies. The viewer must be privy to the cultural codes which make the scene  function, the connotations behind the words uttered by the characters, but once that is appreciated, the words say far more about the position of immigrants in American culture, the difficulty in being a minority in a dominant cultural milieu, the over eagerness not to appear derogatory, and the refusal to admit the blame when wrong.

function, the connotations behind the words uttered by the characters, but once that is appreciated, the words say far more about the position of immigrants in American culture, the difficulty in being a minority in a dominant cultural milieu, the over eagerness not to appear derogatory, and the refusal to admit the blame when wrong.

This piece of dialogue, lost although it is in the flowing tide of repartee of the show, says far more, and less, about North American culture than we want to admit.