The writing community industry is small enough in Canada that even someone like me, who is  tangentially related to the literary world, can often see names I recognize in literary magazines. I also check which books are published by which presses, for that gives me useful, if depressing information about the lay of the land. Although at first blush this sounds as though I am eagerly celebrating the successes of Canadian writers, I am actually more interested in what polite people call networking and the rest of us call nepotism.

tangentially related to the literary world, can often see names I recognize in literary magazines. I also check which books are published by which presses, for that gives me useful, if depressing information about the lay of the land. Although at first blush this sounds as though I am eagerly celebrating the successes of Canadian writers, I am actually more interested in what polite people call networking and the rest of us call nepotism.

Because I have known some Canadian writers personally, I followed their career with interest when they published their work with presses that happened to be where they were living at the time. That intrigued me  because I usually knew they were volunteering or working at the press or had a friend or spouse who had given them the nod. Perhaps because I had been burned by the literary production enterprise, I took a prurient delight in such suggestive coincidences that pointed to nepotism. That opportunities like that are made available in the publishing industry doesn’t shock people who know the trade, but the industry’s blunt flaunting of the practice is sometimes surprising overt.

because I usually knew they were volunteering or working at the press or had a friend or spouse who had given them the nod. Perhaps because I had been burned by the literary production enterprise, I took a prurient delight in such suggestive coincidences that pointed to nepotism. That opportunities like that are made available in the publishing industry doesn’t shock people who know the trade, but the industry’s blunt flaunting of the practice is sometimes surprising overt.

A friend of mine told me I was overly cynical when I suggested that who you know in the publishing world has as much to do with your success as the craft. Only when she unsuccessfully tried to escape from the leg-hold trap of nepotism and patronage—the press founded by her friend which had published her two books—did her way of thinking about the  academic press change. She had always pled that her friend wasn’t necessarily a part of the selection process, but sensitive about the optics, she still looked further afield for her next book. The community was small, and her relationship with the co-founder was well known, at least locally.

academic press change. She had always pled that her friend wasn’t necessarily a part of the selection process, but sensitive about the optics, she still looked further afield for her next book. The community was small, and her relationship with the co-founder was well known, at least locally.

She began by sending poems to a variety of literary journals. She wanted, understandably, to have portions of her book published before she shopped it around to the small presses. She sent poems to Malahat Review  as well as other literary journals whose names I have forgotten, but she was dismayed to find many of them didn’t even bother to reply to her submission. She knew Malahat was famous for its arrogant disregard, but she still believed that her reputation on the Canadian literary stage would at least warrant a form rejection.

as well as other literary journals whose names I have forgotten, but she was dismayed to find many of them didn’t even bother to reply to her submission. She knew Malahat was famous for its arrogant disregard, but she still believed that her reputation on the Canadian literary stage would at least warrant a form rejection.

She tried other literary magazines with similar results. The Canadian literary elite had moved on. She knew some important names from years before, but they didn’t have the clout she needed to get read at the journals where she was submitting her work. Most Canadian writers work at our universities, which both gives them access to literary journals—since the journals are located at universities—and means that they know each other. Canada only has a handful of degree-granting institutions  large enough to have their own presses, so most of them haunt the same halls. They sit on panels which broker literary awards, and they are part of the funding mechanism that feeds the small presses, even as they are coincidentally the beneficiaries of much of that funding.

large enough to have their own presses, so most of them haunt the same halls. They sit on panels which broker literary awards, and they are part of the funding mechanism that feeds the small presses, even as they are coincidentally the beneficiaries of much of that funding.

My friend became snippy when I told her that I had grave misgivings about the system of nepotism  which controlled the slush pile. She disagreed when I said I was so disappointed in the quality of the journal’s rejection letters that I’d given up on the enterprise entirely. They weren’t serious about their work, I told her, but she assured me—at least at the time—that my plaints about the connection between networking and publication were unfounded. A year later she was agreeing with me. The journals had snubbed her, and she realized that the connections she’d taken for granted—likely real friends in her case, not just useful relationships—had disappeared. She said no more about her search for another press, and soon her third book was published by the same press.

which controlled the slush pile. She disagreed when I said I was so disappointed in the quality of the journal’s rejection letters that I’d given up on the enterprise entirely. They weren’t serious about their work, I told her, but she assured me—at least at the time—that my plaints about the connection between networking and publication were unfounded. A year later she was agreeing with me. The journals had snubbed her, and she realized that the connections she’d taken for granted—likely real friends in her case, not just useful relationships—had disappeared. She said no more about her search for another press, and soon her third book was published by the same press.

I also encountered another university connected writer who was writing a book which he was sure would be wildly popular. It struck the right tone, it was topical, and could be marketed to a known demographic. He bragged about movie optioning even while he was writing the first draft. He flew to New York nearly every month to meet with the publisher and editors, and they would discuss the size of print run and translation options. This was all happening without a book in hand.

This apparent success story is undermined by the fact that the author had never written a book. In fact, he’d never published a short story. The publisher had never seen the book, had only heard it described, and they were already setting up the bank account in the Cayman Islands. Such excitement about a book which didn’t exist, as well as such reach for an unknown author, implied nepotism to me. He worked alongside colleagues whose multiple books had never drawn such attention, but they’d also never been as cutthroat about making useful connections. He went on to win a prestigious prize while their books were merely mentioned or shortlisted. Although nothing was said, I couldn’t help but think that they knew how the trick had been done. No press would risk publishing a first book from an unknown author if they weren’t connected, and the shortfall in his prose was made up for by advertising and public relations work.

When I meet aspiring authors who are so confident, I want to know their secret. I’m not as interested in their stories about mornings spent writing and evenings editing. I want to know their real secret. Similarly, a major prize-winning book from twenty years ago was not that well written. In fact it was trite and downright cringe worthy in spots. I wondered, when I met the author, how she had managed its publication and then later won the award. Meeting her did little to inform me. She was incredibly self-centred, and as far as she was concerned she’d earned her credits.

I asked her what she thought of the university, and she heard, “What do you think of you and me?” She thought my inquiry about her new writer in residence gig was a come on. I laughed when she repeated what she’d heard, and then told her what I’d meant more explicitly. When she talked about her work at a reading, she was a little more forthcoming.  She name-dropped several major writers in Canada, and confessed they’d been friends as much as they had mentors. She was only posturing for the crowd, showing how she’d been hobnobbing with the hoi polloi, so she didn’t realize that she was exposing the relationships which had led to the award. She gushed that they’d taken such an interest in her work that they had edited it for her. That explained the prose as well as the award. Such writers would be on the panels which judge such awards, and even if they were not, their

She name-dropped several major writers in Canada, and confessed they’d been friends as much as they had mentors. She was only posturing for the crowd, showing how she’d been hobnobbing with the hoi polloi, so she didn’t realize that she was exposing the relationships which had led to the award. She gushed that they’d taken such an interest in her work that they had edited it for her. That explained the prose as well as the award. Such writers would be on the panels which judge such awards, and even if they were not, their  friends would be.

friends would be.

I might have embarrassed her when I laughed about her guess that I was attracted to her, for she had little more to do with me from that point forward. That in itself is not so unusual, for I recognized the type from the many hallways they haunt at every university. Their first questions are about your status, and when they discover that you are not useful, the plant gets pinched off and the potential relationship dies on the vine. I’ve learned to look for the type over the years. The aspiring writers who eagerly seek the company of the mentor who can give them a leg up, and the young women and men who lay a sticky track of flirtation in order to get their novel read by a press.

Several scandals have rocked the Canadian literary world lately about such  matters, and although many mercenary mentors used their connections to deny publication to those who refused to bed them, I was more interested in the opposite problem. The ones who got published, and how that worked in the system. Like questions about bribery or money laundering, finding the truth about such the system can be difficult. The practices are illegal or immoral, and potentially very embarrassing for all concerned if they are to be found out.

matters, and although many mercenary mentors used their connections to deny publication to those who refused to bed them, I was more interested in the opposite problem. The ones who got published, and how that worked in the system. Like questions about bribery or money laundering, finding the truth about such the system can be difficult. The practices are illegal or immoral, and potentially very embarrassing for all concerned if they are to be found out.

On one level, the publication selection process is at fault. The literary journals in general in the west—and I would include the United States in this statement—are particularly poor at giving all of their submissions equal airing. They receive so many submissions, and their staff—especially in the lower tiers—is typically made up of volunteers or  student interns, so work from an unknown warrants only the most cursory glance. The students bulk-read hundreds of submissions looking for names they’ve been ordered to select, and they basically discard regular submissions unread.

student interns, so work from an unknown warrants only the most cursory glance. The students bulk-read hundreds of submissions looking for names they’ve been ordered to select, and they basically discard regular submissions unread.

To ignore the new writer is to corrupt the purpose of the publishing enterprise, and undermines the most valuable service the journals offer. The increasingly rare Holy Grail—for a writer at least—is a journal which might reject the story but has an employee or volunteer write a cogent comment about the story’s faults. Any good writer knows they are often too close to their work to see its flaws. Unless they belong to a writing community, or are willing to lose friends by asking them to read, they frequently work alone. Without feedback, the writer cannot improve, and if nothing else, the craft of writing is a constant search for ways to improve.

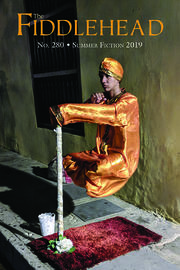

When I still had some misplaced  faith in the system, I sent a magic realist story to The Fiddlehead. The story was set in New Brunswick, like the journal, so I thought it might find a home there. The story is about hundreds of dogs chasing deer through the woods until they become a national spectacle. They are joined by an increasingly unhealthy braggart teen, and the event balloons beyond both physics and logic, until the dogs start to quit. The story is strange, admittedly, and maybe a poor fit for the middle class journals, but I was dismayed that the rejection letter was brief, dismissive, and insulting. Rather than print out a form letter, the undergraduate student who managed the slush pile for the journal scribbled onto a post-it note that “There sure were a lot of dogs.” I had printed out the manuscript, followed the by-times onerous rules which each journal slightly adjusts to individualize its submissions, and included a self-address stamped envelope for the answer as well as my manuscript. The manuscript was never returned, and the smaller envelope only included the post-it note. That was nearly the last time I submitted to the literary journals. That experience neatly symbolized the enterprise, and contrasted vividly with the feedback I had received from science fiction journals.

faith in the system, I sent a magic realist story to The Fiddlehead. The story was set in New Brunswick, like the journal, so I thought it might find a home there. The story is about hundreds of dogs chasing deer through the woods until they become a national spectacle. They are joined by an increasingly unhealthy braggart teen, and the event balloons beyond both physics and logic, until the dogs start to quit. The story is strange, admittedly, and maybe a poor fit for the middle class journals, but I was dismayed that the rejection letter was brief, dismissive, and insulting. Rather than print out a form letter, the undergraduate student who managed the slush pile for the journal scribbled onto a post-it note that “There sure were a lot of dogs.” I had printed out the manuscript, followed the by-times onerous rules which each journal slightly adjusts to individualize its submissions, and included a self-address stamped envelope for the answer as well as my manuscript. The manuscript was never returned, and the smaller envelope only included the post-it note. That was nearly the last time I submitted to the literary journals. That experience neatly symbolized the enterprise, and contrasted vividly with the feedback I had received from science fiction journals.

Although they do not garner the same academic acclaim, the science fiction journals often pay better than the well-heeled literary journals, and accept more experimental work. Rather than exclusively focusing on the concerns of the middle classes and rigid realism, or a shallow notion of avant-garde learned while writing for a MFA, the science fiction journals like Strange Horizons, Asimov’s, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Interzone and Analog publish little known authors as well as those who guarantee sales. In terms of their feedback, at least in my experience, they were more thoughtful and insightful.

On one occasion, the editors at Strange Horizons sent me the critiques from three different readers. Each comment was well considered and observant, and I took their critique to heart when I revised the story. Even though they didn’t accept the story, they took the time to ensure I was on the right track, and pointed me back to the path they thought might best lead to publication. Such experiences ruined me for the academic literary journals, which normally demanded print submissions—and therefore upfront financial investment—and returned unread manuscripts or, more commonly, a form letter in a self-addressed stamped envelope. The return on such investments, both financial and in terms of time, was worthless even if they replied.

I had always read through the offerings of such journals to see what was being published, but as I began to look more carefully at the work they included, the problem became more evident. Beyond the opaque question of nepotism, the journals publish work that interests a rather narrow band of readers. Their middle class stories are by times witty and even clever, but work which expands those boundaries does not often find its way into their pages.

In the interest of full disclosure, for those of you who haven’t read my books, I should admit that I am partially at fault for dismaying the slush pile  readers. I have very little interest in the trials and tribulations of the wealthier classes. I do not write for the middle and upper classes, and rarely write about them. When I do, the portrait is not always flattering. I have written so many stories—a few hundred by this point—that inevitably some of them concern picket-fence realities, and the reaction I get from such stories is worth recounting here when discussing the predictable nature of the Canadian literary world’s interests.

readers. I have very little interest in the trials and tribulations of the wealthier classes. I do not write for the middle and upper classes, and rarely write about them. When I do, the portrait is not always flattering. I have written so many stories—a few hundred by this point—that inevitably some of them concern picket-fence realities, and the reaction I get from such stories is worth recounting here when discussing the predictable nature of the Canadian literary world’s interests.

I approached a mentor one time about looking at some of my stories. He was well known in Canada’s incestuous literary world, and I hoped to make the nepotism work for me. Even though he hadn’t fulfilled his promise of a reference letter years earlier, I thought he might like my stories  well enough to put in a word with his friends at various presses. I gave him four or five stories to read, and so the more acerbic ones didn’t put him off, I included my story “Following Fish.” One of the most middle class stories I’ve written, it tells the story of Frank, a tooth-grinding man on vacation who swims farther and farther into the ocean in an attempt to escape his life. Predictably, the grand old master thought that story was worthy of publication, and he advised me to send it to a literary journal. He was no more help to me than he’d been when I’d waited on a reference letter, and merely told me to format my story and mail it. The other stories apparently didn’t warrant mention, and that interaction cemented my impression of him as well as helped me come to my current understanding of the literary journals’ rather specialized interests.

well enough to put in a word with his friends at various presses. I gave him four or five stories to read, and so the more acerbic ones didn’t put him off, I included my story “Following Fish.” One of the most middle class stories I’ve written, it tells the story of Frank, a tooth-grinding man on vacation who swims farther and farther into the ocean in an attempt to escape his life. Predictably, the grand old master thought that story was worthy of publication, and he advised me to send it to a literary journal. He was no more help to me than he’d been when I’d waited on a reference letter, and merely told me to format my story and mail it. The other stories apparently didn’t warrant mention, and that interaction cemented my impression of him as well as helped me come to my current understanding of the literary journals’ rather specialized interests.

I ran this experiment again, for I am nothing if not a fool. This time I approached the writer in residence at the university. I included a few stories, and the man—another well connected local author—glossed over the other stories in favour of “Following Fish.” He told me to send it to a local journal, and he promised to mention it to the editor when he met him for lunch later that day. Naively, I printed the story and mailed it to the journal. Two weeks later I told him that I’d taken his advice. He didn’t say anything for a moment and then sheepishly confessed that he’d forgotten to mention me to the editor. He wished me luck with the endeavour, and assured me that they might take the story.

I learned two useful lessons from this interaction. By his sheepishness, I knew my form rejection was guaranteed. More importantly, I had some insight into how the system worked. Perhaps unknowingly, he as  good as told me that prospective submissions should be preceded by someone who is connected to the editor. Have he or she put in a good word, and the managers of the slush pile would know what name to search for. If such wasn’t the case, I was convinced, he would never have guiltily admitted he hadn’t fulfilled his promise. He knew he was signing the death warrant of my story, and he had just enough shame to admit it.

good as told me that prospective submissions should be preceded by someone who is connected to the editor. Have he or she put in a good word, and the managers of the slush pile would know what name to search for. If such wasn’t the case, I was convinced, he would never have guiltily admitted he hadn’t fulfilled his promise. He knew he was signing the death warrant of my story, and he had just enough shame to admit it.

After such experiences I began to concentrate more on the non-literary journals. The editors were more forthcoming with feedback—even if they were swamped with work and operating on a shoestring in the absence of government funding—and they seemed to consider work on the basis of its own merit. That doesn’t mean I had picked the lock that would lead me to publications, but occasionally I received an acceptance letter, and I was nearly always assured of a respectful rejection. One editor, or slush pile manager, wrote to me about a story I’d submitted in order to tell me he wanted to have it in the anthology, but it was so strange that he wasn’t sure it would fit. He was compelled by the story, and he wished to keep it for a few more months to evaluate its fit. Such interactions seemed genuine, and although they were not always positive in terms of publication, they were almost always considerate rather than manipulative, and prompt rather than derisive.

Recently, I have become interested in these stories of nepotism. That is partially due to a disturbing essay written by one of my contacts about the matter, and also because I recently submitted a story to an anthology on a whim. After a few months, I received a form rejection—which didn’t shock me—but having submitted to their press meant that I was added to their email list. Therefore, when they sent out notices about the pending publication, I was able to glance over their offerings.

In an update from two months ago they joyfully revealed that they had received more  than seven hundred submissions. They would need more time to evaluate the submissions, the editor suggested, and he guessed at a date we might receive notice. Another month went by and another breathless email gushed about how much they were enjoying the submissions. I wasn’t too concerned over the eventual rejection. At least ninety percent of my stories were rejected, and my ego had never been married to the written text. As well, I knew I was competing with submissions from all over the world. The chances that they would take my story were slim. In the end, they only accepted ten stories. At three to five thousand words per story that seemed to be a slim volume, but I didn’t trouble myself any more about something which was so expressly not my concern.

than seven hundred submissions. They would need more time to evaluate the submissions, the editor suggested, and he guessed at a date we might receive notice. Another month went by and another breathless email gushed about how much they were enjoying the submissions. I wasn’t too concerned over the eventual rejection. At least ninety percent of my stories were rejected, and my ego had never been married to the written text. As well, I knew I was competing with submissions from all over the world. The chances that they would take my story were slim. In the end, they only accepted ten stories. At three to five thousand words per story that seemed to be a slim volume, but I didn’t trouble myself any more about something which was so expressly not my concern.

When another notice of pending publication promised a glimpse of the book cover, I began to look into the press more closely. I might not even have paused over an included photograph a year earlier, but such was the Covid ubiquity that a photograph of the three interviewed  authors together stood out. The only way they could have been photographed together was if they all lived in the same small town. People were not traveling, and even if their work demanded it, they would certainly not travel for a photo shoot. Pondering the coincidence that three out of the ten authors were from the same town, I began to wonder about its population. I initially guessed the town where the press was located had a population of around sixty thousand. I had visited many years earlier, and was relying on my fuzzy memory as well as extrapolating from the size of nearby cities. I consoled myself that three writers out of ten from the same small town might look suggestive, but it wasn’t impossible. A quick search on the population statistics disabused me of that notion. The total population was much closer to fourteen thousand.

authors together stood out. The only way they could have been photographed together was if they all lived in the same small town. People were not traveling, and even if their work demanded it, they would certainly not travel for a photo shoot. Pondering the coincidence that three out of the ten authors were from the same town, I began to wonder about its population. I initially guessed the town where the press was located had a population of around sixty thousand. I had visited many years earlier, and was relying on my fuzzy memory as well as extrapolating from the size of nearby cities. I consoled myself that three writers out of ten from the same small town might look suggestive, but it wasn’t impossible. A quick search on the population statistics disabused me of that notion. The total population was much closer to fourteen thousand.

Mere chance does not  favour such a coincidence. Out of more than seven hundred submissions from all over the world, three people from the same small town—and the writing community would definitely know each other—had their stories chosen. Such a happenstance forcibly reminded me of interactions I’d had with people who ran such small presses. I remembered how they’d had friends submit work, even while others laboured to crack into that rather exclusive—in connections if not in taste—market.

favour such a coincidence. Out of more than seven hundred submissions from all over the world, three people from the same small town—and the writing community would definitely know each other—had their stories chosen. Such a happenstance forcibly reminded me of interactions I’d had with people who ran such small presses. I remembered how they’d had friends submit work, even while others laboured to crack into that rather exclusive—in connections if not in taste—market.

If the stories are of equal quality, then we naturally want to support our friends, but the implications of such numbers leaves a bad taste on the page. The rest of the writers were nearly all white, Canadian, and most of them were from the same province. I wasn’t sure how many others lived in the same small town, for information was scarce on most of them.

I began to dig a bit deeper, seeing what other information I’d overlooked before I’d begun to take an interest. The owner of the press bragged that the over seven hundred submissions had taken him a month to read. I did the math. He read twenty-four stories a day.

If the average story was four thousand words in length—they asked for stories between three and five thousand words—then the overworked editor read ninety-six thousand words every day for a month. He read a novel’s worth of short stories each day, as well as evaluated them before moving on to the next story. Every day for a month. What a paragon of the publishing industry that he would devote so much of his time to his readers.

I don’t want to pretend that my story could compete with seven hundred from around the world, or even that the editor would go through the slush pile as carefully as writers might wish, but I was increasingly intrigued about the circumstances which led to the three writers selected being from the same small town. In their interviews, two of them freely admitted that was their first publication. Another author from the same province said the same.

I looked further into the press. If I had done that before submitting, I would have seen the lone four books in their catalogue as a warning. One book was authored by the press’ owner, another is a novel by one the interviewed writers, who also happened to be an editor at the same press. His book cover was designed by one of the other editors, who edited the anthology I’d submitted to, and that anthology was the third book. The only book which didn’t look like a vanity project was a walking guide, although in an interview with the author, the press owner revealed the man was his friend.

When I was looking for information about the various authors involved in the project, I found that one of the only places that advertised the anthology was a blog. CBC news had carried a brief story about the anthology, but the blog gave more information about its pending publication. I became curious about who was writing the blog. It shared a name with a real literary journal, although it wasn’t associated with it, but those well-trod coattails made it difficult to track. The blog listed no author, but its various news stories provided better counsel. The blog seemed especially interested in the exploits of the same small press. It carried a story about the anthology, as well as introduced the press’ other meagre listings.

I looked through the bios of the blog’s nine followers—for the author of a blog who wants others to follow it will almost certainly follow it themselves. One of the followers was the same editor at the small press who’d had his story accepted in the anthology. Given that the blog advertised other books from that press amongst its more newsy stories, it was likely penned by that same editor. His background in journalism confirmed that suspicion, as much as that was possible, for the blog read more like a local news source than a personal account.

I am deliberately obscuring the name of the press, as well as that of the editors and authors, in this examination. Partially, I am concealing such details in order to save the press the embarrassment in case my few readers uncover the perfidy. Mostly, I am being deliberately vague—even to the point of distorting my diction—because this story is not about a particular press. It is merely a case study in a system of nepotism and self-publishing that is rampant in the Canadian literary scene. My friend didn’t get her poems published by other presses because she wasn’t connected to the editors, and the press which accepted her book published it for the same reasons. The other man who had never written anything had his book optioned before he even had a book, while the award-winning woman pronounced who she’d known who had ensured her book’s success.

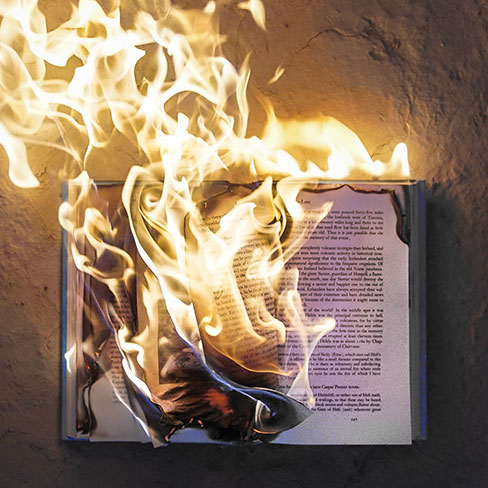

Although the proponents of small presses vehemently proclaim their legitimacy, in many cases they are nothing more than vanity presses in disguise. They are edited by friends, they publish each other’s work, and they ensure their mill grinds only their own flour.

I offer this anecdote to enquire whether the publishing system has been so hijacked that the major presses are printing—if not editing—Fifty Shades of Grey, and the small presses are publishing their friends for academic credit even though the print runs generally produce no more than a few dozen books.

The true losers in this enterprise—although I am tempted to mention the overlooked writers—are the readers. They wonderingly plough through stories written as academic experiments even while they puzzle over how such work was published.  The books published because of nepotism disappear after a few years, when they have done their work of securing tenure or supporting the career of someone’s fawning friend. Then their tiny print run ends, and they go out of print. The presses know what they have done, but the evidence is buried through a complicit lack of interest and poor sales.

The books published because of nepotism disappear after a few years, when they have done their work of securing tenure or supporting the career of someone’s fawning friend. Then their tiny print run ends, and they go out of print. The presses know what they have done, but the evidence is buried through a complicit lack of interest and poor sales.

“We’re not trade publishers,” they proudly proclaim. “We only publish the best.”  They shout this to each other in a closed room over wine even while the warehouse smoulders and the unsold books are alight.

They shout this to each other in a closed room over wine even while the warehouse smoulders and the unsold books are alight.

typically indicates a problem with the alternator—came on while I was driving. My friend was sleeping at the time, and when she woke, she never thought to mention the light to me. The check engine light has long been a constant reminder on my dash and to the colour-visioned, the idea that I wouldn’t notice a red light on a bright day is difficult to remember. By the time she mentioned it to me, some twenty minutes had passed.

typically indicates a problem with the alternator—came on while I was driving. My friend was sleeping at the time, and when she woke, she never thought to mention the light to me. The check engine light has long been a constant reminder on my dash and to the colour-visioned, the idea that I wouldn’t notice a red light on a bright day is difficult to remember. By the time she mentioned it to me, some twenty minutes had passed. the implications of where we were, east of Sault Ste. Marie, and what towns might lay ahead of us. She scoured the internet for towns and I pulled over to disconnect the headlights. Even though it was growing darker in the evening, they were drawing too much power from the battery.

the implications of where we were, east of Sault Ste. Marie, and what towns might lay ahead of us. She scoured the internet for towns and I pulled over to disconnect the headlights. Even though it was growing darker in the evening, they were drawing too much power from the battery. Espanola—which oddly is near Spanish—and began to look up what businesses were available. I didn’t remember much about the town, and wanted to ensure it had a large enough population to support garages that would be open on Sunday. We pulled into town, and got a room at the overpriced rundown Goodman’s hotel which was beside the highway. I mostly chose that one so that I could use the small hill outside the front door to get my car started in the morning, although once we were settled in I wished I would have spent more time looking at others.

Espanola—which oddly is near Spanish—and began to look up what businesses were available. I didn’t remember much about the town, and wanted to ensure it had a large enough population to support garages that would be open on Sunday. We pulled into town, and got a room at the overpriced rundown Goodman’s hotel which was beside the highway. I mostly chose that one so that I could use the small hill outside the front door to get my car started in the morning, although once we were settled in I wished I would have spent more time looking at others. and found out that the Canadian Tire would charge our old battery for free. Therefore, while we sat outside the Tim Horton’s and my friend drank her coffee, our battery was being topped off and we were able to get back on the highway with two fully charged batteries.

and found out that the Canadian Tire would charge our old battery for free. Therefore, while we sat outside the Tim Horton’s and my friend drank her coffee, our battery was being topped off and we were able to get back on the highway with two fully charged batteries. I felt up for trying to replace the dead one, I suggested that we might be able to get to Ottawa, where I could use my friend’s garage and install the alternator myself. As much as I wasn’t looking forward to the job, I am more confident about my bumbling attempts than the rough and ready work of mechanics along the road.

I felt up for trying to replace the dead one, I suggested that we might be able to get to Ottawa, where I could use my friend’s garage and install the alternator myself. As much as I wasn’t looking forward to the job, I am more confident about my bumbling attempts than the rough and ready work of mechanics along the road. hotter, and by late in the afternoon we swapped batteries again. By then a thunderstorm was threatening and it was growing dark. My lights were still disconnected, and I knew the wipers would take away what little power we had in the remaining battery, so while the raindrops were falling, I had my friend look up the address of someone I knew in Deep River. I had called her a week earlier to explain that we had little time and I would not be visiting like I sometimes would, and therefore she knew we would be in the area.

hotter, and by late in the afternoon we swapped batteries again. By then a thunderstorm was threatening and it was growing dark. My lights were still disconnected, and I knew the wipers would take away what little power we had in the remaining battery, so while the raindrops were falling, I had my friend look up the address of someone I knew in Deep River. I had called her a week earlier to explain that we had little time and I would not be visiting like I sometimes would, and therefore she knew we would be in the area. I began to appreciate how great a mechanic we had happened upon, and how difficult the job was. He used his acetylene torch and impact hammer on stubborn bolts, and removed the master cylinder to gain access to the alternator berth. Once he was finished, over an hour later, he suggested forty dollars for his time. That was much below what would normally be charged, and places in the city would have asked for over a hundred. I think he was responding to my old clothes, the old car, and our eagerness to get to Ottawa where I could do the job myself. I gave him seventy, much to his surprise, and we were on our way again.

I began to appreciate how great a mechanic we had happened upon, and how difficult the job was. He used his acetylene torch and impact hammer on stubborn bolts, and removed the master cylinder to gain access to the alternator berth. Once he was finished, over an hour later, he suggested forty dollars for his time. That was much below what would normally be charged, and places in the city would have asked for over a hundred. I think he was responding to my old clothes, the old car, and our eagerness to get to Ottawa where I could do the job myself. I gave him seventy, much to his surprise, and we were on our way again. alternator for us, and a cooler day which would have meant we could have driven into Ottawa. Instead, the one striking coincidence was the mechanic right where and when we needed one.

alternator for us, and a cooler day which would have meant we could have driven into Ottawa. Instead, the one striking coincidence was the mechanic right where and when we needed one. pondering what was wrong with their vehicle, would find themselves not wanting to go too far into the hinterland.

pondering what was wrong with their vehicle, would find themselves not wanting to go too far into the hinterland. manipulating physical reality so that our lives might be easier. The god who plans ahead, sets up a mechanic at exactly the right spot in order that I might find one, is the same god who removed that mechanic from a thousand other drivers. He wasn’t where he needed to be, but instead, luckily, he was where we needed him, and given his willingness to help, and generosity, I’m sure he is where many others will call upon his help as well. We don’t need a capricious god to explain that, any more than we need one to explain the other elements of the car’s deterioration.

manipulating physical reality so that our lives might be easier. The god who plans ahead, sets up a mechanic at exactly the right spot in order that I might find one, is the same god who removed that mechanic from a thousand other drivers. He wasn’t where he needed to be, but instead, luckily, he was where we needed him, and given his willingness to help, and generosity, I’m sure he is where many others will call upon his help as well. We don’t need a capricious god to explain that, any more than we need one to explain the other elements of the car’s deterioration.

alone at the height of the pandemic, the contestants cracked at different times.

alone at the height of the pandemic, the contestants cracked at different times. forage, was expressed in terms of nutrient, protein, or calories. They constantly complained that they needed calories or that they could not go another day without adequate nutrition. I understood their worries, but not their common language. They were from very different backgrounds, classes, professions, and even countries, but none of them consistently called food by that word. Perhaps they thought they were using more scientific nomenclature, or that they would soon seem repetitious

forage, was expressed in terms of nutrient, protein, or calories. They constantly complained that they needed calories or that they could not go another day without adequate nutrition. I understood their worries, but not their common language. They were from very different backgrounds, classes, professions, and even countries, but none of them consistently called food by that word. Perhaps they thought they were using more scientific nomenclature, or that they would soon seem repetitious  if nearly every sentence they uttered used the word food, but whatever the case, I was disconcerted every time they used such stilted expressions for what was a simple plea about their hunger.

if nearly every sentence they uttered used the word food, but whatever the case, I was disconcerted every time they used such stilted expressions for what was a simple plea about their hunger. reminded me of my other book.

reminded me of my other book. He sees a man driving a green car dropping off two other hitchhikers and watches them wave goodbye. That was me, as I drove west one year when I was building my boat. I had picked up two hitchhikers on the edge of Winnipeg, and my narrator saw only the end of a longer trip. Of course, writers normally describe events they have seen in their books, and such incidents from my life—such as when the cops watch the impromptu punker festival in Crab Park—are scattered through that book and others.

He sees a man driving a green car dropping off two other hitchhikers and watches them wave goodbye. That was me, as I drove west one year when I was building my boat. I had picked up two hitchhikers on the edge of Winnipeg, and my narrator saw only the end of a longer trip. Of course, writers normally describe events they have seen in their books, and such incidents from my life—such as when the cops watch the impromptu punker festival in Crab Park—are scattered through that book and others.

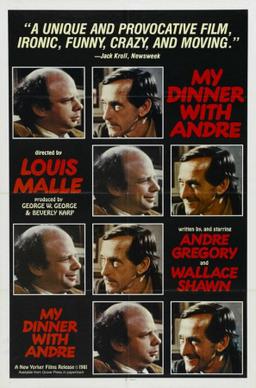

with Andre. Although normally such a declaration would be followed by a revelation about how I was related to one of the actors, perhaps Wallace Shawn who plays an inoffensive man leading a mundane life, that is not the case. I was introduced to the film in a way that highlighted an aspect of interpretation, and although I didn’t know it at the time, I inadvertently learned firsthand about how little we understand ourselves.

with Andre. Although normally such a declaration would be followed by a revelation about how I was related to one of the actors, perhaps Wallace Shawn who plays an inoffensive man leading a mundane life, that is not the case. I was introduced to the film in a way that highlighted an aspect of interpretation, and although I didn’t know it at the time, I inadvertently learned firsthand about how little we understand ourselves. with this pompous bore of a man who goes on about philosophical bullshit and nonsense and how special he is and how he travels all over. So full of shit. And the other guy sits there and listens patiently even though he can’t stand it, and then finally, right near the end of the film, the little guy just devastates him with just a few words. Really puts him in his place and shows him how full of shit he is. Amazing.”

with this pompous bore of a man who goes on about philosophical bullshit and nonsense and how special he is and how he travels all over. So full of shit. And the other guy sits there and listens patiently even though he can’t stand it, and then finally, right near the end of the film, the little guy just devastates him with just a few words. Really puts him in his place and shows him how full of shit he is. Amazing.” When I left my brother’s place that evening, the description stayed with me. Despite his positioning of himself as a stolid family man and his jealousy of my seemingly footloose university student lifestyle, I never thought he might be talking about himself. If I had thought to it, I might have considered that he was trying to make a statement by his way of talking about the film. Instead, if I thought of it at all, I presumed the film would be as he described and that its plot would be pointed toward the comeuppance of the windbag.

When I left my brother’s place that evening, the description stayed with me. Despite his positioning of himself as a stolid family man and his jealousy of my seemingly footloose university student lifestyle, I never thought he might be talking about himself. If I had thought to it, I might have considered that he was trying to make a statement by his way of talking about the film. Instead, if I thought of it at all, I presumed the film would be as he described and that its plot would be pointed toward the comeuppance of the windbag. distracted man who takes the train back to his apartment and wife while pondering his childhood and the many different paths his life might have taken.

distracted man who takes the train back to his apartment and wife while pondering his childhood and the many different paths his life might have taken. Instead, he bragged about his house, about the pay from his job, and even though he was usually broke, he thought of himself as the success of the family. Importantly, that success was measured by what others in the family did not have. If someone was travelling then that affront to his staid nature defined the other person, and if someone were poor, that confirmed his wealth.

Instead, he bragged about his house, about the pay from his job, and even though he was usually broke, he thought of himself as the success of the family. Importantly, that success was measured by what others in the family did not have. If someone was travelling then that affront to his staid nature defined the other person, and if someone were poor, that confirmed his wealth. Wally’s obvious delight in Andre’s stories, their shared interest in philosophical questions, and the close bonding the two share. In order to get his fantasy of their mutual discord, my brother focused on their discussion about how possible Andre’s life was for ordinary people. He chose to ignore Wally’s re-examination of his life on the way home from the restaurant, and the film’s lack of resolution just to he could justify the normal man—and Wally is anything but—sticking it to the egghead intellectual. His need for an ugliness in the film drowned out its beauty, and he merely told a story about his own insecurities and jealousies, his willingness to ignore evidence to further emotional goals, and how he really felt about his life.

Wally’s obvious delight in Andre’s stories, their shared interest in philosophical questions, and the close bonding the two share. In order to get his fantasy of their mutual discord, my brother focused on their discussion about how possible Andre’s life was for ordinary people. He chose to ignore Wally’s re-examination of his life on the way home from the restaurant, and the film’s lack of resolution just to he could justify the normal man—and Wally is anything but—sticking it to the egghead intellectual. His need for an ugliness in the film drowned out its beauty, and he merely told a story about his own insecurities and jealousies, his willingness to ignore evidence to further emotional goals, and how he really felt about his life.

tangentially related to the literary world, can often see names I recognize in literary magazines. I also check which books are published by which presses, for that gives me useful, if depressing information about the lay of the land. Although at first blush this sounds as though I am eagerly celebrating the successes of Canadian writers, I am actually more interested in what polite people call networking and the rest of us call nepotism.

tangentially related to the literary world, can often see names I recognize in literary magazines. I also check which books are published by which presses, for that gives me useful, if depressing information about the lay of the land. Although at first blush this sounds as though I am eagerly celebrating the successes of Canadian writers, I am actually more interested in what polite people call networking and the rest of us call nepotism.

academic press change. She had always pled that her friend wasn’t necessarily a part of the selection process, but sensitive about the optics, she still looked further afield for her next book. The community was small, and her relationship with the co-founder was well known, at least locally.

academic press change. She had always pled that her friend wasn’t necessarily a part of the selection process, but sensitive about the optics, she still looked further afield for her next book. The community was small, and her relationship with the co-founder was well known, at least locally. as well as other literary journals whose names I have forgotten, but she was dismayed to find many of them didn’t even bother to reply to her submission. She knew Malahat was famous for its arrogant disregard, but she still believed that her reputation on the Canadian literary stage would at least warrant a form rejection.

as well as other literary journals whose names I have forgotten, but she was dismayed to find many of them didn’t even bother to reply to her submission. She knew Malahat was famous for its arrogant disregard, but she still believed that her reputation on the Canadian literary stage would at least warrant a form rejection. large enough to have their own presses, so most of them haunt the same halls. They sit on panels which broker

large enough to have their own presses, so most of them haunt the same halls. They sit on panels which broker  which controlled the slush pile. She disagreed when I said I was so disappointed in the quality of the journal’s rejection letters that I’d given up on the enterprise entirely. They weren’t serious about their work, I told her, but she assured me—at least at the time—that my plaints about the connection between networking and publication were unfounded. A year later she was agreeing with me. The journals had snubbed her, and she realized that the connections she’d taken for granted—likely real friends in her case, not just useful relationships—had disappeared. She said no more about her search for another press, and soon her third book was published by the same press.

which controlled the slush pile. She disagreed when I said I was so disappointed in the quality of the journal’s rejection letters that I’d given up on the enterprise entirely. They weren’t serious about their work, I told her, but she assured me—at least at the time—that my plaints about the connection between networking and publication were unfounded. A year later she was agreeing with me. The journals had snubbed her, and she realized that the connections she’d taken for granted—likely real friends in her case, not just useful relationships—had disappeared. She said no more about her search for another press, and soon her third book was published by the same press. She name-dropped several major writers in Canada, and confessed they’d been friends as much as they had mentors. She was only posturing for the crowd, showing how she’d been hobnobbing with the hoi polloi, so she didn’t realize that she was exposing the relationships which had led to the award. She gushed that they’d taken such an interest in her work that they had edited it for her. That explained the prose as well as the award. Such writers would be on the panels which judge such awards, and even if they were not, their

She name-dropped several major writers in Canada, and confessed they’d been friends as much as they had mentors. She was only posturing for the crowd, showing how she’d been hobnobbing with the hoi polloi, so she didn’t realize that she was exposing the relationships which had led to the award. She gushed that they’d taken such an interest in her work that they had edited it for her. That explained the prose as well as the award. Such writers would be on the panels which judge such awards, and even if they were not, their  friends would be.

friends would be. matters, and although many mercenary mentors used their connections to deny publication to those who refused to bed them, I was more interested in the opposite problem. The ones who got published, and how that worked in the system. Like questions about bribery or money laundering, finding the truth about such the system can be difficult. The practices are illegal or immoral, and potentially very embarrassing for all concerned if they are to be found out.

matters, and although many mercenary mentors used their connections to deny publication to those who refused to bed them, I was more interested in the opposite problem. The ones who got published, and how that worked in the system. Like questions about bribery or money laundering, finding the truth about such the system can be difficult. The practices are illegal or immoral, and potentially very embarrassing for all concerned if they are to be found out. student interns, so work from an unknown warrants only the most cursory glance. The students bulk-read hundreds of submissions looking for names they’ve been ordered to select, and

student interns, so work from an unknown warrants only the most cursory glance. The students bulk-read hundreds of submissions looking for names they’ve been ordered to select, and  faith in the system, I sent a magic realist story to The Fiddlehead. The story was set in New Brunswick, like the journal, so I thought it might find a home there. The story is about hundreds of dogs chasing deer through the woods until they become a national spectacle. They are joined by an increasingly unhealthy braggart teen, and the event balloons beyond both physics and logic, until the dogs start to quit. The story is strange, admittedly, and maybe a poor fit for the middle class journals, but I was dismayed that the rejection letter was brief, dismissive, and insulting. Rather than print out a form letter, the undergraduate student who managed the slush pile for the journal scribbled onto a post-it note that “There sure were a lot of dogs.” I had printed out the manuscript, followed the

faith in the system, I sent a magic realist story to The Fiddlehead. The story was set in New Brunswick, like the journal, so I thought it might find a home there. The story is about hundreds of dogs chasing deer through the woods until they become a national spectacle. They are joined by an increasingly unhealthy braggart teen, and the event balloons beyond both physics and logic, until the dogs start to quit. The story is strange, admittedly, and maybe a poor fit for the middle class journals, but I was dismayed that the rejection letter was brief, dismissive, and insulting. Rather than print out a form letter, the undergraduate student who managed the slush pile for the journal scribbled onto a post-it note that “There sure were a lot of dogs.” I had printed out the manuscript, followed the  readers. I have very little interest in the trials and tribulations of the wealthier classes. I do not write for the middle and upper classes, and rarely write about them. When I do, the portrait is not always flattering. I have written so many stories—a few hundred by this point—that inevitably some of them concern picket-fence realities, and the reaction I get from such stories is worth recounting here when discussing the predictable nature of the Canadian literary world’s interests.

readers. I have very little interest in the trials and tribulations of the wealthier classes. I do not write for the middle and upper classes, and rarely write about them. When I do, the portrait is not always flattering. I have written so many stories—a few hundred by this point—that inevitably some of them concern picket-fence realities, and the reaction I get from such stories is worth recounting here when discussing the predictable nature of the Canadian literary world’s interests. well enough to put in a word with his friends at various presses. I gave him four or five stories to read, and so the more acerbic ones didn’t put him off, I included my story “Following Fish.” One of the most middle class stories I’ve written, it tells the story of Frank, a tooth-grinding man on vacation who swims farther and farther into the ocean in an attempt to escape his life. Predictably, the grand old master thought that story was worthy of publication, and he advised me to send it to a literary journal. He was no more help to me than he’d been when I’d waited on a reference letter, and merely told me to format my story and mail it. The other stories apparently didn’t warrant mention, and that interaction cemented my impression of him as well as helped me come to my current understanding of the literary journals’ rather specialized interests.

well enough to put in a word with his friends at various presses. I gave him four or five stories to read, and so the more acerbic ones didn’t put him off, I included my story “Following Fish.” One of the most middle class stories I’ve written, it tells the story of Frank, a tooth-grinding man on vacation who swims farther and farther into the ocean in an attempt to escape his life. Predictably, the grand old master thought that story was worthy of publication, and he advised me to send it to a literary journal. He was no more help to me than he’d been when I’d waited on a reference letter, and merely told me to format my story and mail it. The other stories apparently didn’t warrant mention, and that interaction cemented my impression of him as well as helped me come to my current understanding of the literary journals’ rather specialized interests. good as told me that prospective submissions should be preceded by someone who is connected to the editor. Have he or she put in a good word, and the managers of the slush pile would know what name to search for. If such wasn’t the case, I was convinced, he would never have guiltily admitted he hadn’t fulfilled his promise. He knew he was signing the death warrant of my story, and he had just enough shame to admit it.

good as told me that prospective submissions should be preceded by someone who is connected to the editor. Have he or she put in a good word, and the managers of the slush pile would know what name to search for. If such wasn’t the case, I was convinced, he would never have guiltily admitted he hadn’t fulfilled his promise. He knew he was signing the death warrant of my story, and he had just enough shame to admit it. than seven hundred submissions. They would need more time to evaluate the submissions, the editor suggested, and he guessed at a date we might receive notice. Another month went by and another breathless email gushed about how much they were enjoying the submissions. I wasn’t too concerned over the eventual rejection. At least ninety percent of my stories were rejected, and my ego had never been married to the written text. As well, I knew I was competing with submissions from all over the world. The chances that they would take my story were slim. In the end, they only accepted ten stories. At three to five thousand words per story that seemed to be a slim volume, but I didn’t trouble myself any more about something which was so expressly not my concern.

than seven hundred submissions. They would need more time to evaluate the submissions, the editor suggested, and he guessed at a date we might receive notice. Another month went by and another breathless email gushed about how much they were enjoying the submissions. I wasn’t too concerned over the eventual rejection. At least ninety percent of my stories were rejected, and my ego had never been married to the written text. As well, I knew I was competing with submissions from all over the world. The chances that they would take my story were slim. In the end, they only accepted ten stories. At three to five thousand words per story that seemed to be a slim volume, but I didn’t trouble myself any more about something which was so expressly not my concern. authors together stood out. The only way they could have been photographed together was if they all lived in the same small town. People were not traveling, and even if their work demanded it, they would certainly not travel for a photo shoot. Pondering the coincidence that three out of the ten authors were from the same town, I began to wonder about its population. I initially guessed the town where the press was located had a population of around sixty thousand. I had visited many years earlier, and was relying on my fuzzy memory as well as extrapolating from the size of nearby cities. I consoled myself that three writers out of ten from the same small town might look suggestive, but it wasn’t impossible. A quick search on the population statistics disabused me of that notion. The total population was much closer to fourteen thousand.

authors together stood out. The only way they could have been photographed together was if they all lived in the same small town. People were not traveling, and even if their work demanded it, they would certainly not travel for a photo shoot. Pondering the coincidence that three out of the ten authors were from the same town, I began to wonder about its population. I initially guessed the town where the press was located had a population of around sixty thousand. I had visited many years earlier, and was relying on my fuzzy memory as well as extrapolating from the size of nearby cities. I consoled myself that three writers out of ten from the same small town might look suggestive, but it wasn’t impossible. A quick search on the population statistics disabused me of that notion. The total population was much closer to fourteen thousand. favour such a coincidence. Out of more than seven hundred submissions from all over the world, three people from the same small town—and the writing community would definitely know each other—had their stories chosen. Such a happenstance forcibly reminded me of interactions I’d had with people who ran such small presses. I remembered how they’d had friends submit work, even while others laboured to crack into that rather exclusive—in connections if not in taste—market.

favour such a coincidence. Out of more than seven hundred submissions from all over the world, three people from the same small town—and the writing community would definitely know each other—had their stories chosen. Such a happenstance forcibly reminded me of interactions I’d had with people who ran such small presses. I remembered how they’d had friends submit work, even while others laboured to crack into that rather exclusive—in connections if not in taste—market.

The books published because of nepotism disappear after a few years, when they have done their work of securing tenure or supporting the career of someone’s fawning friend. Then their tiny print run ends, and they go out of print. The presses know what they have done, but the evidence is buried through a complicit lack of interest and poor sales.

The books published because of nepotism disappear after a few years, when they have done their work of securing tenure or supporting the career of someone’s fawning friend. Then their tiny print run ends, and they go out of print. The presses know what they have done, but the evidence is buried through a complicit lack of interest and poor sales. They shout this to each other in a closed room over wine even while the warehouse smoulders and the unsold books are alight.

They shout this to each other in a closed room over wine even while the warehouse smoulders and the unsold books are alight.